How the Tokyo Olympics became the Achilles heel for Japan’s prime minister

Yoshidhide Suga’s decision to step down brings to a close a year-long tenure marred by viral surges and miscalculations, writes David McElhinney in Tokyo

Back in January, Yoshihide Suga told his fellow parliamentarians the Tokyo Olympics would stand as “proof of human victory against the coronavirus”. With Covid-19 cases mounting a record-breaking ascent as the five-ringed crusade rocked into town, the prime minister’s assertion began to look less like a crystal-ball ball prediction, more like an ill-timed jinx.

For Suga, the Olympics became increasingly make or break, and the recent announcement he would not be re-running for the premiership in the autumn general election shows the pendulum has swung towards the latter. His decision closes the curtain on a year-long tenure marred by viral surges, increasingly vocal public discord, and stifled political progress.

Perhaps unfortunately, it’s impossible to view Suga’s reign through any other prism than that of the Games. As the pandemic refused to abate, his continued pro-Tokyo 2020 rhetoric put unprecedented levels of international scrutiny upon every decision he and his cabinet made. It also helped to detract from some of his more positive moves, like setting a net zero target for 2050, pushing for digital reforms, and encouraging cheaper competition in the mobile data-provision market.

Questions were raised over Suga’s willingness to line the pockets of the International Olympic Committee (IOC) by hosting a party of almost 80,000 Games-accredited arrivals amid the persistent viral threat and widespread public opposition. This was set against the backdrop of Japan’s sluggish vaccination rate, which – despite having the world’s third largest economy and third largest pharmaceutical industry – was the lowest out of all 38 OECD countries as recently as April.

Aside from unconvincing and scripted retorts in conference rooms, Suga’s policies for dealing with peaking and troughing waves of Covid-19 were muddled and impulsive. Rigid border protocols, which prevented valid visa- and certificate of eligibility-holders from entering the country, were foregone for Tokyo 2020 participants.

Half-baked state of emergencies came thick and fast. The latest, Tokyo’s fourth, was instated (or reinstated) from 12 July until 22 August, but is still periodically being extended. It has disproportionately affected the hospitality industry, with the government asking bars and restaurants to close by 8pm and refrain from selling alcohol, while non-Olympic sports venues, theatres, cinemas, and shopping malls are still welcoming visitors.

Suga might have got away with such mixed messaging if the data hadn’t been so damning. His assurance Tokyo could hold a “safe and secure” Olympics crumbled when Japan’s 7-day average of Covid-19 cases climbed from around 3,000 prior to the Games to around 23,000 by the end of August, smashing all previous records. Furthermore, it was later discovered the potentially super-infectious Covid-19 Lambda variant was brought to Japan on the eve of Tokyo 2020 – by a person with Olympic accreditation – before the administration attempted (and failed) to cover it up.

Since Tokyo 2020, Suga’s support among the public has been a continuously ebbing tide. An NHK poll in August put the cabinet’s approval rate at 29 per cent, while the disapproval rate jumped to a record 52 per cent.

Now all eyes are on who comes next. There are fears Japan will return to the revolving-door syndrome which plagued the nation’s top political post in previous decades. In the 21st century alone, 10 prime ministers have held office, one of whom – Shinzo Abe – was elected twice and served a national record of almost nine years.

Suga’s Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) currently holds a supermajority with 278 seats of the 465 available in the Lower House, Japan’s legislative chamber. This means that the newly elected president of the LDP, which will be decided internally on 29 September, will be favourite for the prime minister’s office. The LDP’s main opposition, the Constitutional Democratic Party (CDP), holds only 113 seats and are unlikely to mount a serious challenge.

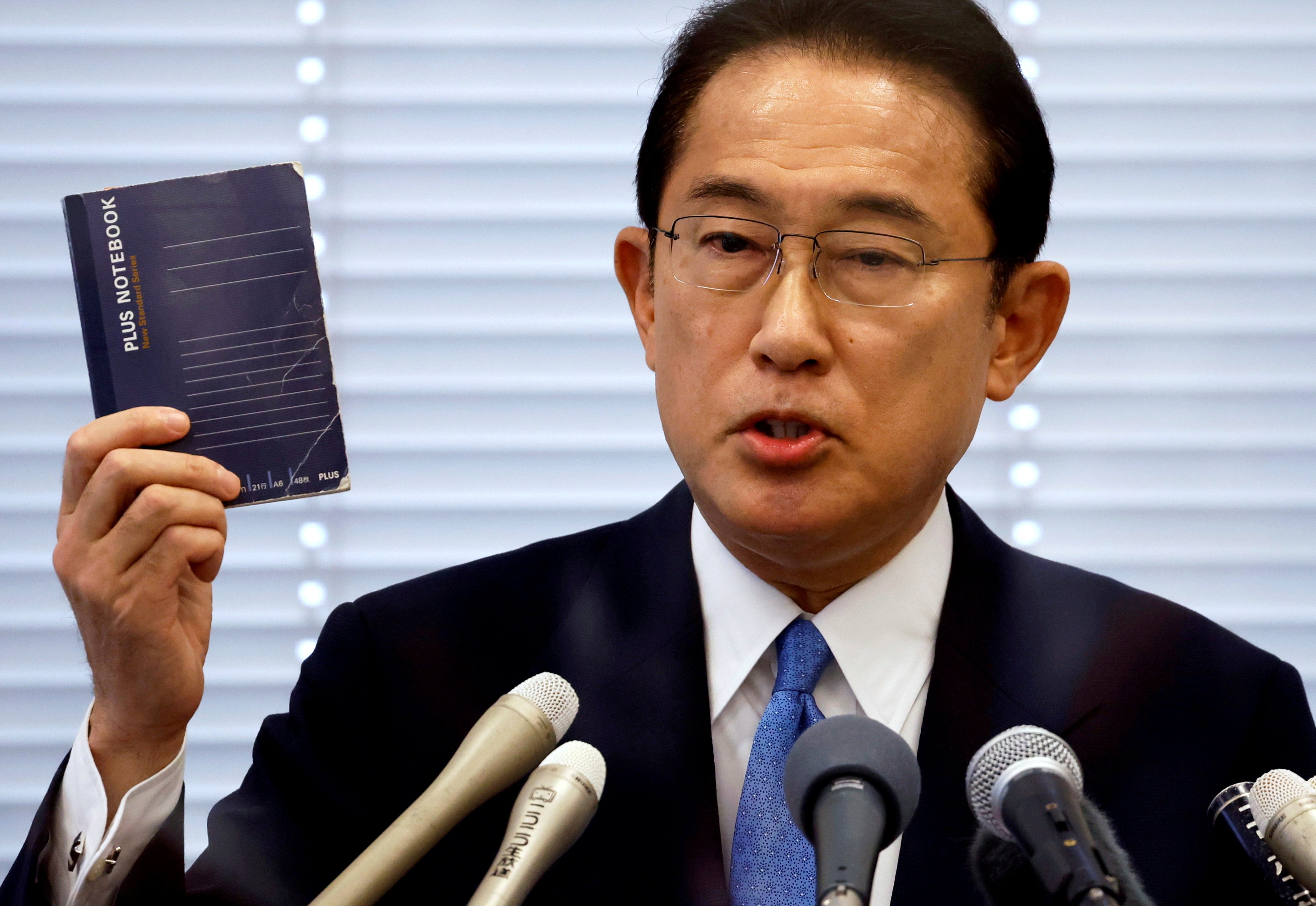

Unsurprisingly, the three frontrunners to succeed Suga are elderly, male career politicians who grew up enmeshed in the world of Japan’s political dynasties: Taro Kono, Shigeru Ishiba, and Fumio Kishida. In a recent Kyodo News poll on who should take the LDP reins, they received 31.9 per cent, 26.6 per cent and 18.8 per cent of the vote, respectively.

Kono, the current administrative reform minister, has been backed by the departing Suga. He also spearheaded Japan’s remarkable vaccine turnaround this summer, which now sees one million shots administered daily, and has been an ardent proponent of vaccine passports which could help open Japan’s bolted-shut internationals borders. Moreover, Kono is favoured by younger voters and is expected to be one of the few politicians that could instate lasting political change and a system where meritocratic values trump blood ties.

Ishiba and Kishida are both popular among the LDP seniority, heading their own factions within the party. That said, they are less popular with the voter base than the maverick Kono.

Ishiba is a former defence minister and banker, meaning his policies are likely to be hawkish and fiscally conservative – though growing up on the quiet west coast of Japan, he talks a big game on decentralising power from Tokyo. Ishiba has also taken a hard stance on Chinese hegemony, which will be a major geopolitical headache for Japan in the coming years.

Kishida comes from an old blue-blood political family in Hiroshima, and after losing out to Suga in the race to become Abe’s successor last year, would be welcomed by the LDP elite. He’s promising big on economic stimulus packages for post-pandemic recovery, meaning households, businesses and contract workers could be in for further cash handouts, though this would doubtless be challenged by the power-wielding ministerial bureaucrats. Kishida has also been criticised for his lack of charisma, but Suga has proven this isn’t necessary to land the job.

Whoever claims the premiership will be deeply embroiled in recovery mode for the foreseeable future. But as the shadow of Tokyo 2020 continues to recede, the balancing act between economic and public health concerns will be that bit easier to manage. And frankly, Suga hasn’t plagued his successor with a tough act to follow.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments