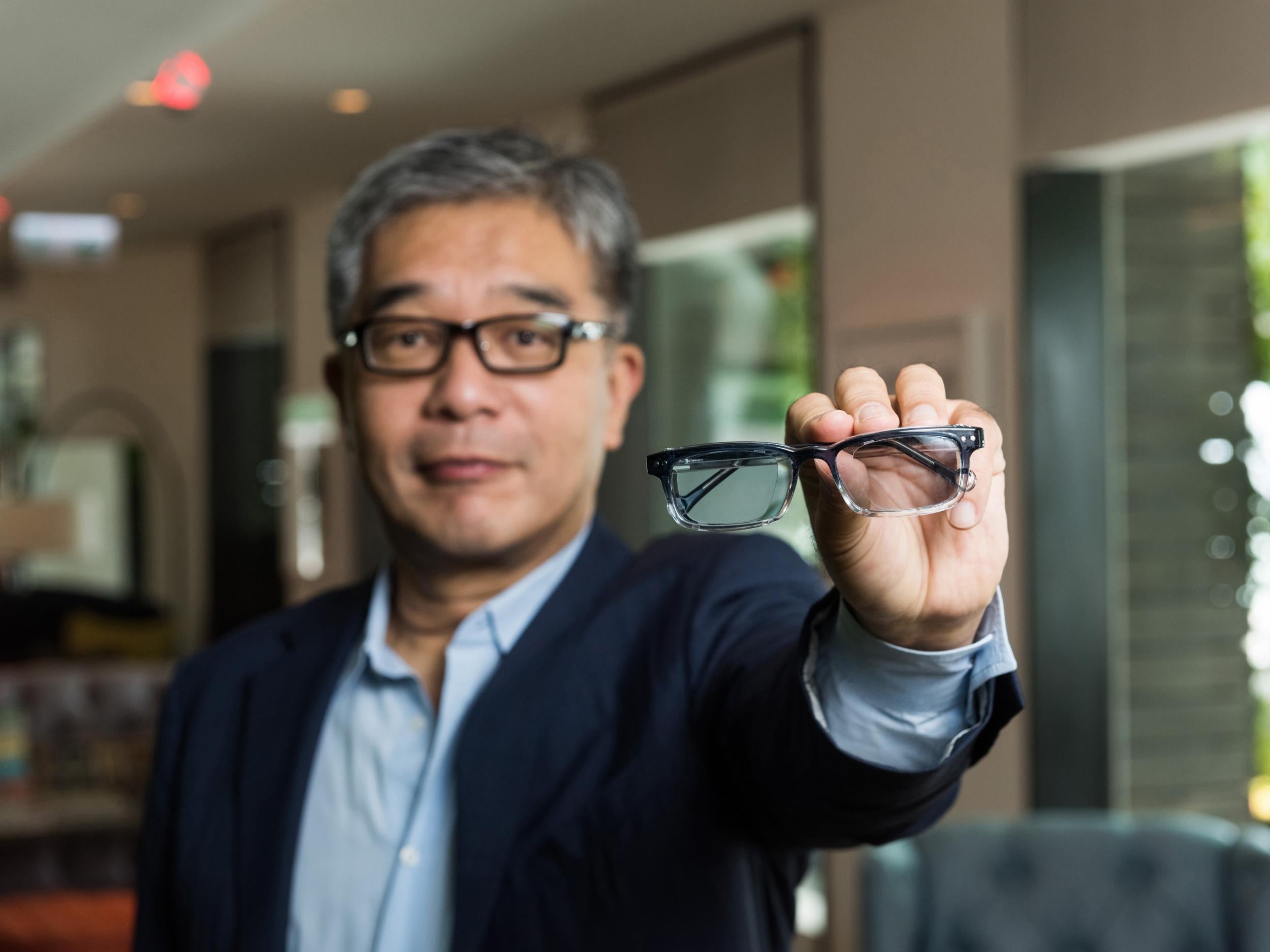

Why James Chen is a man on mission to restore eyesight for all by 2035

The Hong-Kong businessman is using the wealth generated by his family’s business for greater good. He tells Zlata Rodionova that philanthropy is not about writing big cheques

Futurist and inventor Elon Musk wants to send humans to Mars by the 2030s but James Chen has a no less ambitious mission: making sure the whole world can see the landing clearly when it happens.

For the past 15 years the philanthropist has been trying to tackle poor vision. According to Chen, the pace of innovation can be overwhelming when compared with the lack of progress in technology designed to tackle the most basic challenges still facing the developing world, from access to food and clean water to a simple pair of corrective glasses.

“We really want to solve the ‘vision issue’ before Nasa or Elon Musk put a man or a woman on Mars because we want everyone on Earth to be able to see it,” he says.

“It seems to me that if the world has the technological prowess and the political will to put someone on Mars then they should be able to harness the power of a pair of glasses – a very simple 700-year-old technology that would benefit everyone in the world today,” he tells The Independent.

The scale of the rarely talked about “vision issue” is impressive. About 2.5 billion people worldwide suffer from poor eyesight and some 80 per cent of these are concentrated in 20 developing countries, mostly in Africa and Asia.

These preventable, diagnosable and treatable conditions equate to over $227bn (£173bn) in lost productivity each year, according to the World Economic Forum, which argues that poor sight is a barrier to education and employment, trapping families in poverty.

There’s a good likelihood parents will not get these girls the glasses they need because there is a cultural belief that girls with glasses are considered too smart and therefore their marriage prospects could be hindered

“During the time I spent in Nigeria, and later on in developing parts of Asia, it struck me that very few people wore glasses, and it was very much at the back of mind – is it because they don’t need them or is it because they don’t have access them? Today, of course, I know the answer,” Chen says.

In addition to access, correct diagnosis, distribution, financial resources and demand are the other challenges preventing people from seeing clearly. “People who never had their vision tested and corrected don’t know what they are missing. In developing countries people may also choose to use their disposable income for something else, which is completely understandable,” he says.

There are also cultural barriers. Chen cites India as a country where parents worry that glasses might hinder their daughters’ marriage prospects. “There’s a good likelihood parents will not get these girls the glasses they need because there is a cultural belief that girls with glasses are considered too smart and therefore their marriage prospects could be hindered.”

Fortunately, entrepreneurial resilience and the ability to take risks and tackle challenges is something that has run in Chen’s family for three generations.

Born in Hong Kong, raised in Nigeria and educated between England, New York and Chicago, Chen says he feels “blessed” and “humbled” to be able to help drive the change that may affect the lives of hundreds of millions of people for the better today.

It is Wahum Group Holdings, a manufacturing business based in Nigeria, which he now chairs, that has made these activities possible. A third generation family owned company, it now employs 1,200 people in three factories.

Built by his grandfather after he fled China in 1947, Chen says his family didn’t expect the company to be a success. “As it was based in developing countries at the time the family assumed it wouldn’t last that long. In fact, my cousins and I were actively discouraged to consider the family business as a real career alternative – but it’s still going strong.”

His example has been an extremely strong influence. He taught me that philanthropy is not about writing cheques but it’s about putting time and effort into understanding what is needed to help

His father was the one who taught him the importance of philanthropy from an early age. “As a 7-year-old my father had experienced starvation so when he retired he really wanted to give back to his home village in China.

“Unlike many of his peers, who were just very willing to write big checks, he spent a lot of time on location working with local officials and speaking to people. This means that the impact of his giving was much greater.”

“His example has been an extremely strong influence. He taught me that philanthropy is not about writing cheques but it’s about putting time and effort into understanding what is needed to help.”

Chen’s own mission began when when he met Joshua Silver, an Oxford professor who had developed a prototype of an adjustable lens – glasses that can change their strength, depending on what you’re using them for.

Compared to made-to-order glasses, the single pair of specs was a more affordable option serving a wide range of needs.

“One of the challenges of getting eyewear to people is the distribution problem. For many places it’s impossible or prohibitory expensive. So the idea of a pair of glasses with adjustable lenses meant that you could simplify the distribution and reduce the cost to get the product into the consumer’s hands,” Chen says.

To develop and investigate the technology, he first co-founded Adlens in 2005, followed in 2011 by Vision for a Nation, a charity supporting emerging nations by providing them with eye-care and glasses – starting with Rwanda.

At the time, most people he turned to for help, from high-net-worth individuals to the agencies dealing with the developing world, told him the vision problem couldn’t be solved.

“From the developing-world perspective, they have to prioritise life-and-death issues – but sometimes they fail to connect the dots. For example, some agencies will fund adult literacy classes in Africa but many people over 35 living in these areas have poor vision. So how can they learn to read if they can’t see?” Chen says.

“These organisations have very little appetite for risk tolerance. But this is where I can be different. With private capital, you can recognise that if it the project fails, it’s your money and if you are willing to accept that, you can back things that are more risky.

“A project failure doesn’t need to have a negative connotation. Scientists do that, they have a hypothesis, they’ll test it, they’ll fail, they’ll learn and then they’ll come up with a new hypothesis. We are really trying to apply that same discipline in business. The only difference is I am able to do it using my family’s money rather than risking taxpayers or shareholders’ funds.”

In 2017, the foundation trained 2,000 nurses in Rwanda who worked across a network of clinics to assess a patient’s eye problems and whether they needed glasses. As a result, two and a half million out of the total population of 12 million were screened.

Any Rwandan citizen can now buy a pair of glasses for $1.50, equivalent to five days’ income – although the poorest 20 per cent get them for free from the government, according to Chen.

“The main challenge we saw in Rwanda was the diagnostic issue, so we commissioned a brilliant ophthalmologist, who developed a three-day training protocol for nurses. We also had a partnership with the ministry of health to utilise Rwanda’s national health clinic network.

“Coming out of Rwanda, we actually came up with a model that could solve the problem – even though highly trained professionals told us that it couldn’t be done.”

In 2016, Chen launched the Clearly campaign, which looks at ways to replicate the method used in Rwanda around the world, and bring together government leaders, innovative businesses, technologists and specialists to find a solution to this global problem.

“Last year, I believe we scored a big success when the Clearly campaign along with other vision partners lobbied the commonwealth leaders to recognise the vision issue and make them commit to make eye care affordable to all.”

In addition to running a global campaign, Chen is also a father-of-three and says his children are his proudest achievement. “I don’t have much free time but when I do I try to spend time with my kids. We all love to travel as a family.”

A lifelong foodie, Chen tried to make it into the food business by opening his first restaurant at the age of 23 – and ultimately had to close it after just two years in business

Today he is a part owner of a few successful restaurants. “Some people would describe it as an investment but for me it’s an indulgence and a pleasure,” he explains.

While missing the mark never feels good, Chen thinks experiencing failure was a valuable lesson to learn so early on in his career and it should not stop entrepreneurs from trying again. “When you’re younger the consequences of failing is lower but it’s also very sobering to have that experience. You’re much more grounded and you don’t get carried away that easily,” he says.

“If you had an idea, you tested It and it failed, what’s more important is what you learn from that failure and how you changed your hypothesis.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments