Averroes: Perhaps the most important of the Islamic philosophers

Our series moves onto the Renaissance philosophers, starting with Ibn Rushd, known as Averroes, whose life and work reflected tensions that were endemic in Islamic society at this time

Ibn Rushd (1126–98), known in the west as Averroes, is perhaps the most important of the Islamic philosophers who emerged during the golden era of intellectual flourishing that occurred in the Muslim world in the several hundred years around the turn of the first millennium. His life and work reflected tensions that were endemic in Islamic society at this time.

Ibn Rushd was born in 1126 in Cordova, Spain, into a well connected family of jurists and theologians. His grandfather and father both held the office of chief judge (qadi) of Cordova under the then ruling Almoravids dynasty (a position to which Averroes would later ascend). His education, though in a sense orthodox for a Muslim male, was by our standards eclectic: Qur’anic exegesis, the Hadith, jurisprudence (Fiqh), scholastic philosophy, mathematics and linguistics were all studied, and became part of his intellectual armory. “Moreover, under the tutelage of Abu Jafar Harun, Ibn Rushd attained a proficiency in medicine, which eventually enabled him to become the royal physician to the Almohad caliphs Abu Yaqub Yusuf and Abu Yusuf Yaqub. Indeed, such were his abilities in this field that his book Generalities (Kulliyat) was perhaps the most significant general medical text in the Judeo-Christian and Islamic worlds for several hundred years after his death.

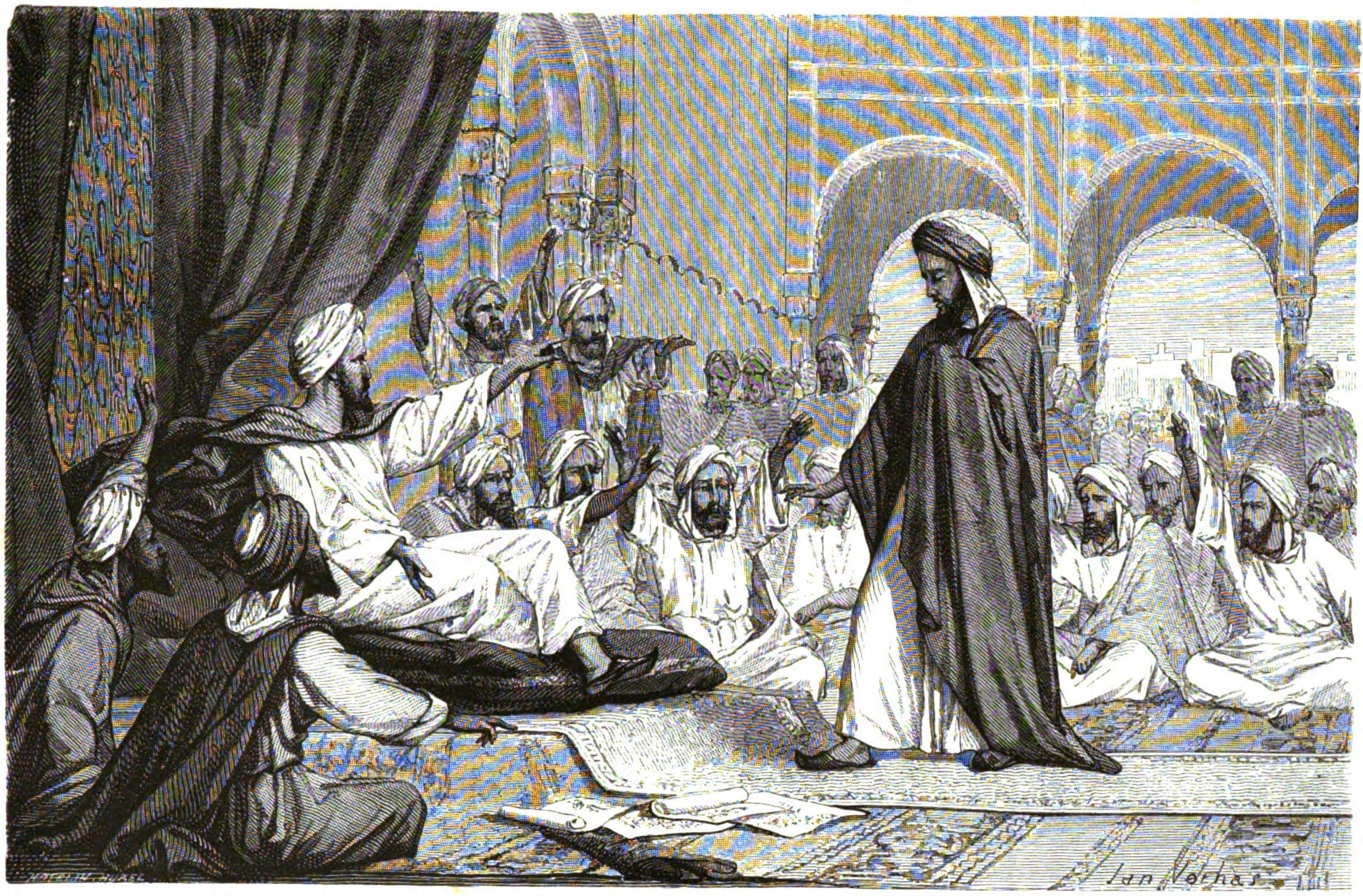

It was Ibn Rushd’s connections within the royal court that led him by happenstance to the most significant body of work of his life. He had been introduced to the caliph, Abu Yaqub, by his mentor Ibn Tufail, who at that time was the court physician. The story has it that the caliph thoroughly unnerved the young philosopher by asking him whether the heavens were created or not. This seems an innocuous enough enquiry, but it was the kind of question that could get a Muslim philosopher into trouble. The difficulty is that a negative response potentially places a limit on the power of God, whereas an affirmative response runs the danger of anthropomorphising him. The caliph, a keen philosopher himself, spared Ibn Rushd’s blushes by answering his own question, and then engaging in a long discussion of the issues surrounding it. Shortly afterwards, Ibn Rushd received word that the caliph believed the works of Aristotle to be disjointed, rather obscure, and therefore likely to confuse people. The solution was simple – Ibn Rushd should write commentaries on them.

“Twenty-six years later, Ibn Rushd completed this task (as far as it was possible). Based on Arabic translations, the commentaries took three different forms. The shortest (Jami) were simple summaries, suitable for anybody who wanted just a flavour of the work. The intermediate commentaries (Talkhis) were appropriate for normal studies. And then there were the Tasfir – detailed analyses of Aristotle's work, incorporating Qur'anic concepts, which were suitable for advanced study. Ibn Rushd did not have access to Aristotle’s Politics, so instead he commented on Plato’s Republic, arguing that the original Islamic community was equivalent to Plato’s ideal state.

According to Oliver Leaman, a leading scholar of Islamic and Judaic philosophy, the most impressive aspect of these commentaries is that Ibn Rushd was able to resurrect Aristotle’s original arguments by ridding them of the Neoplatonist baggage they had gained over time. His technique was to approach the texts as though they were new, and then to reconstruct their arguments on authentically Aristotelian lines. Leaman argues that although Ibn Rushd was not always successful, and though he was not shy about adding his own comments to the text, his work on Aristotle remains impressive.

The tension between philosophy and religion that characterised this era found perfect expression in the dispute that formed the basis of Ibn Rushd’s most important work of original philosophy

Although Ibn Rushd enjoyed the protection of royal patronage, he was not entirely able to avoid the unpleasantness that almost inevitably occurs when religious orthodoxy runs up against intellectual freedom. In 1195, at the age of 70, with the Almohad caliph under pressure to do something about the liberalising tendencies within Islamic society, he was formally exiled from Cordova, his writings were banned, and his books burned. Though quickly back in favour, and allowed to return home, he did not live much longer, and questions about his orthodoxy persisted. Indeed, his influence in the Muslim world quickly declined after his death, as Islam embarked on a path that all but extinguished the sort of intellectual life that bred philosophers as great as Al-Farabi (Alpharabius), Ibn Sina (Avicenna) and Ibn Rushd himself.

The tension between philosophy and religion that characterised this era found perfect expression in the dispute that formed the basis of Ibn Rushd's most important work of original philosophy, The Incoherence of Incoherence (Tahiifut al-Tahiijut). This is a defence of philosophical reason against its critics. Its specific target was the Islamic theologian and mystic Al-Ghazali (Algazel), who had written The Incoherence of the Philosophers (Tahiijut al Faliisifa), in which he attacked philosophy, and in particular the work of Ibn Sina, for being self-contradictory and un-Islamic.

Al-Ghazali’s attack was multidimensional – commentators have identified at least 17 different points of contention, but perhaps the most interesting issues have to do with God as a freely acting agent able to intervene in the world in any way that he chooses. Consider, for example, the question that caliph Abu Yaqub posed to the young Ibn Rushd – are the heavens created? The Islamic philosophers who were the focus of Al-Ghazali’s ire had tended to argue that they were not. Ibn Sina’s view, for instance, was “emanationist”: he claimed that the universe was not created ex nihilo at a particular moment in time, but rather that it exists out of necessity, emanating in manifold forms from God’s divine nature.

Obviously, this is a highly esoteric conception of God, and to the uninitiated likely it makes little sense, but certainly it didn’t please Al-Ghazali. It is easy to see why – it seems to do away with God as a free agent. Al-Ghazali’s response to all this was to argue that the Qur’an is quite clear that the universe was created by God. If God is an agent, able to act according to his own will, then it is perfectly reasonable to suppose that he created the world ex nihilo, and that he could eliminate it again should he so choose. In effect, then, Al-Ghazali defends a particular conception of divine agency: God is all powerful, therefore, he can act to create and destroy worlds.

Ibn Rushd’s critique of Al-Ghazali’s view of divine agency is exemplary in terms of the kinds of argumentative techniques that he employed. He argued that Al-Ghazali goes wrong by mixing up the temporal and the eternal. It is quite reasonable to suppose that temporal beings (ie, humans) can decide to embark upon some course of action, then delay doing so, then begin, then stop, and then start again, but it doesn’t work that way for God. Consider, for example, what follows from God’s omniscience and omnipotence: God will always know the best arrangement for the universe, and he will always be able to instantiate it, so it doesn't make sense to think that he might choose not to instantiate it at a particular moment in time. To put this another way, there is nothing internal nor external to his nature that might lead him to delay the moment of creation.

Similar kinds of difficulties afflict Al-Ghazali's position if one reflects upon God’s perfection. God is eternal and unchanging. This makes it problematic to suppose that he has desires that he might act upon in the same way that human beings have desires that they act upon. The idea of desire suggests some kind of perturbation in God’s nature, which is then annulled when the desire is fulfilled. But this makes no sense, since it implies a change in God’s nature – and as we have seen God’s nature is eternal and unchanging. It seems to follow then that God’s acts must simply be a manifestation of his nature, and that they are not willed in the same way that human beings will their acts.

It is easy to see why this kind of argument might get an Islamic philosopher into trouble. As Al-Ghazali suggested, it does seem to do away with God’s agency – his freedom to choose. Although Ibn Rushd denied this particular criticism, he was aware that there was a general issue about the impact of philosophical arguments on less sophisticated believers. In his work Decisive Treatise (Fasl al-Maqal), he argued that it is clear from the Qur’an that there is an obligation to attempt to understand the world through the study of philosophy:

That the Law summons to reflection on beings, and the pursuit of knowledge about them, by the intellect is clear from several verses of the Book of God, Blessed and Exalted, such as the saying of the Exalted, “Reflect, you have vision”: this is textual authority for the obligation to use intellectual reasoning, or a combination of intellectual and legal reasoning. Another example is His saying, “Have they not studied the kingdom of the heavens and the earth, and whatever things God has created?”: this is a text urging the study of the totality of beings.

However, Ibn Rushd did not think that the arguments of philosophers were suitable for general consumption. In particular, where philosophy leads to conclusions that conflict with the apparent meaning of scripture, then it should be kept from the ordinary masses. He was quite clear that there could be no real conflict between philosophical truth and scripture – any disagreement simply meant that an allegorical reading of scripture was required. This had long been accepted as a legitimate way of proceeding by the Muslim community, which meant that Al-Ghazali, and the other critics of philosophy, were wrong to claim that philosophers were indulging in unbelief when they questioned doctrines such as the creation of the universe or bodily resurrection.

Nevertheless, Ibn Rushd did believe that in order to serve the end of the collective wellbeing of the Muslim community, it was necessary for teachers to modify their arguments depending upon the audience that they were addressing. To attempt to teach the ordinary faithful about a higher interpretation of scripture when they do not have the conceptual apparatus to understand it almost inevitably harms their faith, and thereby affects the happiness of the community as a whole. Philosophical enquiry is sanctioned by God, but it requires the kinds of talent and rigorous training that necessarily means it will be suited only to a minority of people.

Ibn Rushd’s philosophical arguments on religious matters were not entirely defensive. He also developed a number of arguments in favour of the existence of God, contending that the fact that the world fits so neatly with the purposes of human beings, and the fact that all living things are clearly the work of a designer, is proof of God’s reality. And, as we have seen, he wrote influentially on non-religious matters. However, even if it ultimately failed, it is for his defence of philosophical reason, which he mounted in the face of considerable opposition, that he is rightly celebrated.

Major works

The Incoherence of Incoherence is Ibn Rushd's most influential work. It is a defence of philosophy against the strictures of religious orthodoxy as manifest in Al-Ghazali's criticisms of Al-Farabi and Ibn Sina’s The Incoherence of the Philosophers.

Decisive Treatise is a work of apologetics directed towards those theologians who accuse philosophers of unbelief. It develops the argument that any apparent conflict between philosophy and scripture simply means that scripture has to be read allegorically – a practice with a long tradition within Islam. It follows that the philosophers are not guilty of unbelief when they question aspects of scripture about which there is no general consensus.

Commentaries on Aristotle is Ibn Rushd’s commentaries on the works of Aristotle, which became central to the way in which Aristotle was understood in Christian Europe.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks