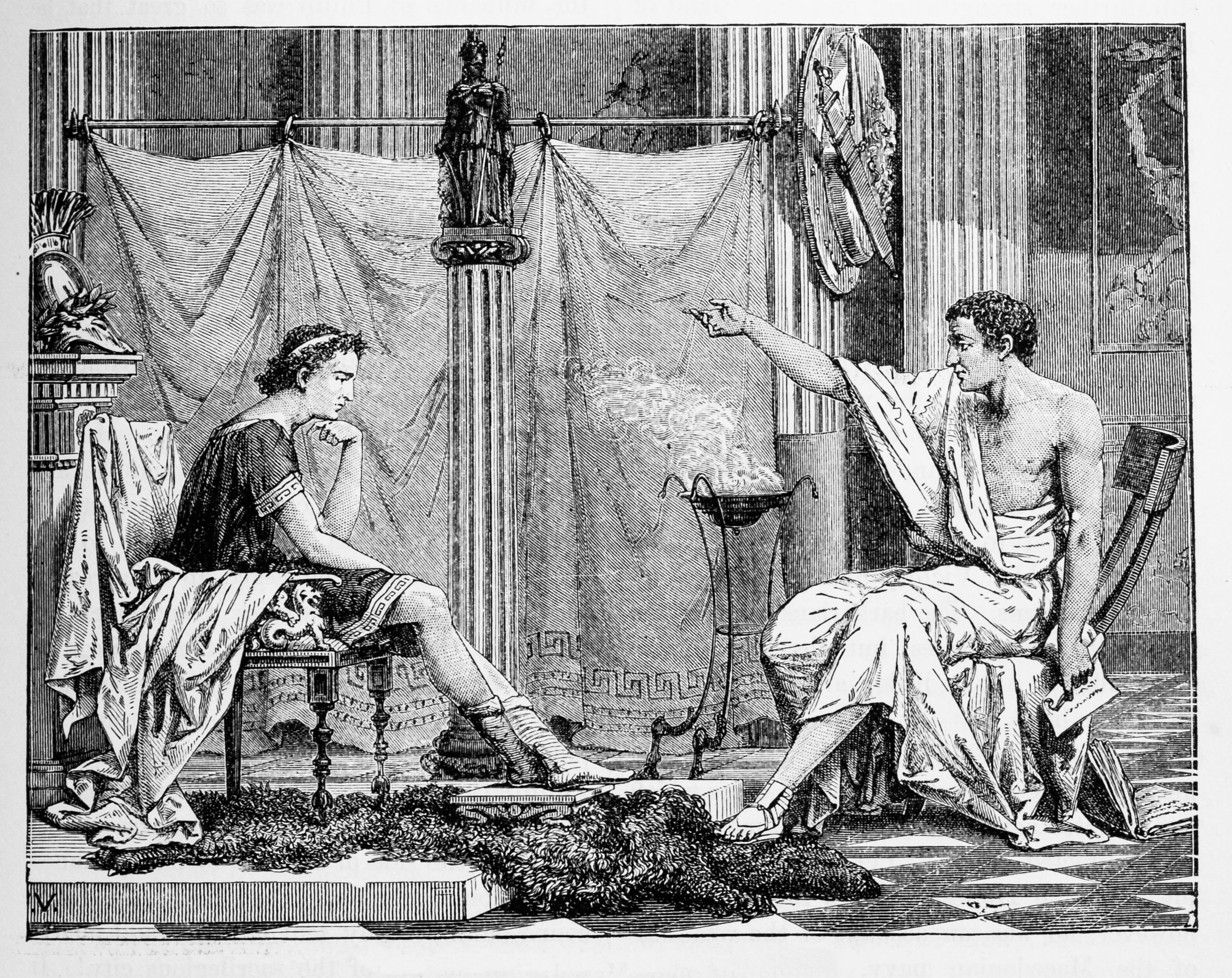

Aristotle, father of logic and founder of western philosophy

In the first of a new series introducing the lives and works of some of history’s greatest minds, we examine the thought and legacy of the peripatetic philosopher Aristotle, whose ideas are as vital and alive today as they were in ancient Greece

Imagine that you are Plato, coming to the end of your years, presiding over the now-famous Academy, enjoying a reputation among both your students in particular and Athenians in general. You hear, perhaps while lingering in a doorway, a murmured reference to the “Reader”, the “Mind of the Academy”.

They are not talking about you, but a young upstart from the sticks, perhaps only 17 years old, called Aristotle. Would you find this galling?

In truth, we can only speculate about the relationship between Plato and Aristotle (384–322BC). We know that Aristotle’s father, a physician to the court of the King of Macedon, sent him to Athens when he was about 17 and that he joined the Academy, remaining there for 20 years, first as a student and eventually as a teacher. In the year that Plato died, Aristotle departed – no one knows whether he remained out of loyalty to Plato and left on the master’s death, or departed in disgust, having not been offered control of the school. We do know that his father’s connections led him to Macedonia, to tutor a 13-year-old, the future Alexander the Great.

After years of travel and study, he returned to Athens and founded the Lyceum, or peripatetic school – so named either because lectures were conducted on the move or in honour of the locale’s fine walkways. Here he remained until 323BC, when, so the story goes, his Macedonian connections and Athens’ anti-Macedonian mood led to his being formally charged with impiety, as they had done with Socrates – Athens being nothing if not consistent. Allegedly claiming that he would not let the city sin twice against philosophy, he fled to Chalcis, where he died the following year.

He produced an enormous body of work. Ancient commentators distinguish between his esoteric and exoteric writings – the former were highly technical pieces, written for use within the school, and the latter well-crafted pieces for public consumption. We know he wrote dialogues. We have Cicero’s word that the public works were things of beauty, a “golden river of eloquence”. No such works survive. We have only his technical, esoteric writings, and these are not beautiful in the usual sense, but are compact, crammed with jargon and what seem like technical preoccupations, stilted, and generally lacking in literary virtue. Actually, we have what are probably his lecture notes. They are works in progress, edited by those who came after, and discrepancies and inconsistencies sometimes confound us. Few, though, would be willing to trade even a scrap of it for a part of the public writings: though rough-going, Aristotle’s surviving writings are crammed with the fruits of an incredible intellectual power.

The rules of logic

Aristotle more or less invented and formalised the rules of right reasoning, the beginnings of philosophical logic. He was the first to study the nature of deduction, to say what it means for a proposition to follow of necessity from premises, to identify and formalise different possible sorts of syllogism. With a general notion of proof in hand, he formalised the relation between the evidence gathered by studying things in the world and coming to true conclusions about those things. In doing this, he did much more than point us in the direction of what we now recognise as science. This alone would have been beyond impressive and earned him a large place in history, but his writings on logic and methodology constitute only a part of the Aristotelian corpus. Aristotle was just getting started when he invented science.

The virtue, or excellence, of a thing for Aristotle consists in the full development of the distinctive potentialities latent in its particular nature

He wrote enormously influential treatises on ethics, politics, metaphysics, physics, mathematics, psychology, poetry, rhetoric, aesthetics, meteorology, geology, methodology, cosmology, philosophy of mind, theology, psychology, memory, and dreams, among much else. It is not going too far to say that he invented entire disciplines, whole regions of enquiry which still occupy us. More than this, Aristotle was the first to engage in the practice of distinguishing between different subject-matters; recapitulating and considering a topic’s intellectual history; explicitly identifying the standards of evidence, degrees of precision, questions, and so on proper to each. Aristotle not only invented whole disciplines, he invented the very notion of a discipline.

All of this is to say nothing of his biological writings, which constitute perhaps a quarter of what we have. In a letter to William Ogle, a famous translator of Aristotle’s biological works, Darwin mentions his “two gods” Linnaeus and Cuvier, concluding that they were “mere schoolboys to old Aristotle”. It took a lot of thinking, nearly two thousand years of thinking, to get beyond Aristotle’s teleological or goal-directed conception of life and the parts of animals. All of it follows from his famous four causes. The word “cause” is a little misleading, and one might just think of the four causes as the four explanatory features of a thing that we get by asking four sorts of question.

Questions of nature

To use Aristotle’s example, we might ask four questions about a statue: what is it made of (bronze: its material cause); what sort of thing is it (a statue: its formal cause); what brought it into being or initiated the changes that led to its being what it is (a sculptor: its efficient cause); and what is it for (decoration: its final cause). One gets a feeling from this that Aristotle is preoccupied with goals and ends, and it is true that Aristotle denies that we really know a thing, even a natural object or organ, until we know what it is for, what it aims at or does.

You will notice that Aristotle departs radically from Plato in this. Knowledge of this world is possible without recourse to a permanent realm of Forms. On the contrary, forms or universals exist only in the things in this world, and knowledge consists not in the contemplation of Forms, but in getting one’s hands dirty, examining and dissecting and poking the things of this changing world, coming to know their causes. In the case of statues and other artefacts, form is imposed by some outside agency; while in the case of natural objects, Aristotle argues, internal principles direct the thing such that it becomes what it naturally becomes.

Of those natural objects which live – plants, animals and human beings – Aristotle’s answer to the four questions of cause consists largely in the activity of soul. The soul, for Aristotle, is not something ghostly which inhabits the body. Instead it is, at least in part, the distinctive functioning of the body in question –what initiates its movement fixes its aims. To oversimplify more than a little, a plant’s soul is vegetative, and as such it consists in growing; an animal’s soul consists in this plus movement, appetite and the power to sense certain things; a human being’s soul consists of this, plus the power to think and know.

The virtue, or excellence, of a thing for Aristotle consists in the full development of the distinctive potentialities latent in its particular nature. An excellent plant, then, is one which manifests the full flowering (literally) of the plant soul: it grows very well indeed. An excellent horse is one which realises the potentialities of the distinctive movements of horses: it covers the ground; perhaps its quick eye and attentive ear contribute to its fleetness. Excellence or virtue for humans insofar as we are rational consists in action in accordance with reason. This, Aristotle famously claims, consists in choosing the mean.

Choosing the mean

Virtue consists in choosing the mean between two extremes, that is, in feeling and acting rightly given all the peculiar circumstances of a situation. If one faces mortal danger, Aristotle argues that courage consists in choosing the mean between the excesses of foolhardy rashness on one side and cowardice on the other. When one speaks about oneself, the virtue of truthfulness consists in choosing the mean between boasting and undue modesty. It is clear that Aristotle is not advocating what one might mistake for a Christian ethics of unqualified moderation. The mean varies from person to person and situation to situation. Thankfully, Milo the wrestler can choose his own mean when ordering the wine; an amount fine for him but excessive for the rest of us. There is nothing absolutist or exhaustive about Aristotle’s notion of the mean: there is no mean when it comes to murder, he tells us. The best we can do is employ reason and decide on a case-by-case basis.

Of what does the good life consist, given this view of virtue? Aristotle maintains that the good life requires friendship. Genuine virtue requires not only fellowship with equals, but sometimes self-sacrifice of varying sorts. Without friends, such action is not possible, and therefore a fully virtuous life is not possible. Friends afford the opportunity for goodness and happiness.

It is difficult to imagine Aristotle satisfied with a treatise, content in the state of his own thinking on some matter or another, supposing, ‘Well, that’s all there is to know about that’

In addition, the full flowering of the intellectual virtues, the realisation and exercise of our distinctive mental faculties, is required. Our rational capacities are part of what makes us what we are – just as a knife’s capacity to cut makes a knife a knife. A good knife is one which cuts well, and a good human life is one filled with thinking well. A good life is certainly one in which we choose the mean, but it is also one in which rationality is given its head. Of the many goods we might aim at, the highest good, Aristotle argues, is the contemplative life, the life of the mind.

On with the inquiry

This is, of course, only a caricature of the vast Aristotelian corpus. It overlooks many of the tensions, not to say outright contradictions, in his writing, and glosses over some very difficult technical philosophy. It is worth remembering, when we read him, that what we have really are works in progress, probably under constant revision throughout his life. It is difficult to imagine Aristotle satisfied with a treatise, content in the state of his own thinking on some matter or another, supposing, “Well, that’s all there is to know about that”. Aristotle was not so easily satisfied. Aristotle was also not one to waste last lines, and it is worth remembering the last line of the Nicomachean Ethics when faced with difficulties of interpretation. It is a long and bold treatise, dealing with more or less all thinking on ethics extant in Aristotle’s time. He writes, at the end of what looks like a comprehensive account of virtue: “Come, let us get on with the inquiry.”

Major works

We cannot say exactly when Aristotle wrote what has come down to us. It is likely that later editors made some changes and put the work in the order that it has now. Here is just some of it:

Nicomachean Ethics is among the most influential treatises on morality ever written. It contains a fascinating consideration of human happiness and virtue. It is perhaps most interesting for making the claim, forgotten by many later thinkers, that morality cannot be reduced to a series of universal principles.

Politics says something about the ideal state, which for Aristotle is one with the goal of well-being for its citizens. You will find here some disturbing remarks on slavery and the need for social harmony, which are partly mitigated by a consideration of the merits of democracy.

Physics is interesting for its consideration of the nature of explanation in what looks like budding science, as well as treatments of space and time.

Next Week: Plato

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments