‘Just not that likeable’ – the woman who shattered the glass ceiling with landmark Supreme Court ruling

Bosses accused her of walking and talking like a man but Ann Hopkins challenged Price Waterhouse on sex discrimination and won, and author Gloria Romero wants everyone to know her story, writes Andrew Buncombe

Gloria Romero says she had not even heard the name Ann Hopkins until she started researching her book into gender discrimination. By the time she had finished, she had made it her mission to share with as many people as possible the story of the courageous individual who, three decades ago, won a landmark case at the nation’s highest court, a ruling that opened the doors for women across America.

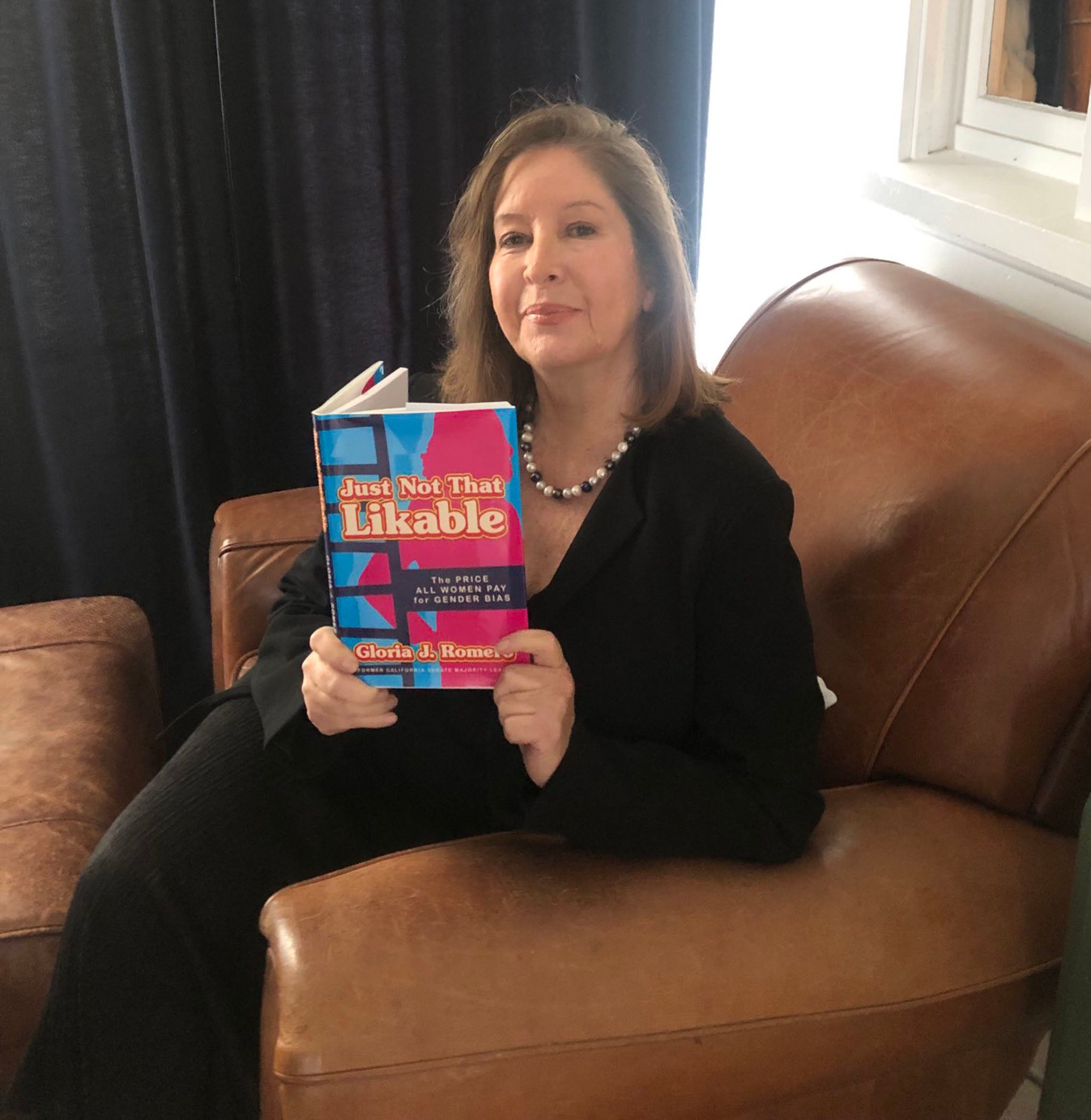

“My hope is that people will know who she is, what she stood for, and really [appreciate] the doors she’s opened up on this very important issue that we rarely talk about,” says Romero, author of Just not that Likeable: The Price all Women Pay for Gender Bias.

Hopkins, who died in 2018, made history when in 1989 the US Supreme Court ruled in her favour after she sued her former employer, Price Waterhouse, as the company was then known, after she accused it of repeatedly failing to promote her to partner. Even though Hopkins had excellent evaluations, and bagged the company a $44m contract with the US State Department, her bosses told her she was too “macho” and bossy. One manager said she needed to take a charm course.

After fighting for seven years in lower courts, the Supreme Court ruled 6-3 in her favour, deciding that gender discrimination was barred by title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. That clause is intended to prevent employment discrimination based on race, colour, religion, sex and national origin.

“An employer who objects to aggressiveness in women but whose positions require this trait places women in an intolerable and impermissible Catch-22 – out of a job if they behave aggressively, and out of a job if they don’t,” wrote Justice William Brennan in his lead opinion.

Following the decision, Hopkins, who drank beer, wore high heels and once drove a motorbike to a job interview, received around $400,000 in back pay. Then she moved on to to a new job with the World Bank. “The explanation I got about why I didn’t make partner didn’t make sense to me,” Hopkins said of the judgement. “I filed suit not because of the money, but because I had been given an irrational explanation for a bad business decision.”

Romero, 66, a former California state senator whose district included parts of east Los Angeles, herself knows a thing or two about battering on glass ceilings.

In 2005, she became Democratic leader of the California Senate, the first woman to hold the position. She knows too, about people commenting on her looks, her clothes, her voice, about being told she was too pushy or bossy. After leaving the senate in 2010 and moving into education and academia, the comments continued.

“We expect men to succeed. We expect men to lead. We expect men to be in charge, to command, even to demand,” she writes. “But for women? Not so much. Indeed, one of the most pernicious and persistent barriers to women’s advancement is the ‘mismatch’ between qualities associated with leadership, as opposed to qualities associated with women.”

Romero tells The Independent a lot of gender discrimination is often subtle and sometimes subconscious, which can make it harder to address. “When I left the Senate I was really surprised when people said ‘Gloria, you stand up when you speak… you use your hands, you look directly at people, you look into people’s eyes, you don’t avert your gaze. Maybe you should talk more gently’,” she says.

She says the prescriptions heaped on her were very similar to those levelled on Ann Hopkins back in the 1980s. “She was told she couldn’t really smoke cigarettes. She couldn’t ride a motorcycle. She shouldn’t wear a leather jacket. She talked too loud. She needed to basically almost put herself in a corset, and sit down and shut up,” says Romero.

“Even though we’ve made progress, the same old gender stereotypes are there. And that’s what I’m writing about this – because I’ve seen it in my career. In writing the book, I’ve talked to a lot of women. And they have said, ‘Gloria, we have all felt the same thing. We’ve been told the same thing’. And these were successful women leaders in corporate America or in politics.”

Among some of the findings of the research conducted by Romero, an adjunct at the Pepperdine University School of Public Policy in Malibu, is that 42 per cent of women experience gender discrimination at work; men are 30 per cent more likely to obtain managerial roles than women; and while women represent a third of MBA graduates, just four per cent of the CEOs of Fortune 500 companies are women.

Very often, one of the most obvious places where gender discrimination plays out in the public eye is in politics.

In 2016, commentators from across the political field described Hillary Clinton’s voice as “shrill”. In 2020 Elizabeth Warren was told she was “squeaky”, while nobody less than the then-president of the United States, Donald Trump, described Kamala Harris as “nasty”.

Was Romero surprised by such offensive and discriminatory language used in mainstream discourse during the last two presidential campaigns to describe women candidates? “It didn’t surprise me. But it did dismay me because I have been talking about this as part of the course I teach on gender stereotyping,” she says.

“If you think about it, Elizabeth Warren, irrespective of politics, it doesn’t matter if one likes their platform or not, but she is a well-credentialled, well-qualified, intelligent woman. What did they say? ‘Oh well, you know, she didn’t smile, she was angry.’ And then there’s Bernie Sanders. And I love and adore Bernie Sanders, but he [is presented] as very affable and lovable and yet he was always yelling at people.”

She says the situation is far worse for women of colour and minorities. She writes of stereotypes of “the angry Black woman”, “ the fiery Latina” or the “Asian tiger mom”. She says women of a certain age also suffer gender stereotyping, and are often talked of as “menopausal mood-swinging matriarchs”.

Romero talks less of a glass ceiling, than a labyrinth of discrimination that women need to navigate and deal with. She stresses her book is not a 10-step solution to overcoming the challenges, but a first stage is to talk about the problem and call gender discrimination what it is. People need to know the story of Ann Hopkins and they need to learn the law. “We have to know our history to move forwards,” she says. She is also convinced women need to get over “the need to be liked”.

“It’s OK to be called a witch. And the word that rhymes with witch,” she says. “It’s OK to talk loud and have somebody tell us that our voices screech. So we have to get over that. And that’s very challenging because we’re in a world of social media, on Facebook and Twitter, everything depends upon getting likes.”

She says she does not encourage women to necessarily be tyrants, but they must stop wishing to be “Little Miss Suzie manners, sugar and spice everything nice”.

“We have to stand up and say it’s OK for us to be strong. And quite frankly, it’s OK to be called a bitch,” she says. “Because as I told my daughter when she was called a bitch, when she was in elementary school, all that means is you stood up for yourself.”

Romero says women also need to be prepared to use the law and file discrimination suits. “I think all of us have to speak out. It can’t just be women who are the gender police,” she says. She says men need to act as allies, and women also need to realise that other women are not always on their side, as they can often discriminate and claim they prefer to have male bosses.

Ann Hopkins, who was told by her bosses to “walk more femininely, talk more femininely, [and] dress more femininely”, had three children. She died in 2018 from the effects of acute peripheral sensory neuropathy, a rare illness with symptoms that include paralysis. One of her children, Tela Gallagher Mathias, says from Washington DC, that her mother had been a “reluctant civil rights landmark”.

“With my mother, you either loved her or hated her. The same is probably true with me,” says Mathias, a senior technology executive who says she also frequently encounters gender discrimination. She recently had to ask the male CEO of a major consulting firm who was visiting her offices to call the female employees “women” and not “girls”.

More recently, the decision Hopkins won has been used by those campaigning for gay and transgender rights. In 2019, a year after her mother’s death, Mathias visited the Supreme Court as activists for LGBT+ rights sought to use her mother’s title VII victory to secure their constitutional rights after they were fired for their sexual preferences or gender discrimination. “My mother and these LGBTQ employees were punished for refusing to adhere to society’s expectations,” she wrote at the time.

She tells The Independent: “It was really quite a day for me to be there in the courtroom, and to hear them talking about my mum and talking about the case.”

While many may assume the court is a large building, there is a not a lot of room for members of the public, she says. She and one of her mother’s sisters were among the last 10 people admitted that day. “That was a very emotional day,” she says, adding that as a child, people of every “race, creed and colour” visited her mother’s house.

“All these people wanted her to hear about their cases that they wanted to bring to court, and the various injustices that they had faced, so it was always part of my life.”

Romero says that more than 30 years after that Supreme Court decision in favour of Hopkins, her book is one of just a handful on the topic of gender discrimination. “It is time for us to act up for Ann Hopkins… Act up for ourselves, for our daughters and sisters, and under a constitution and a growing body of social science research and law that recognises and respects us for the tenacity and strength of our character,” she writes.

“It has to end somewhere. But first it has to start. And that typically means that someone needs to raise her hand, raise her voice, just outright object to what is taking place, has been taking place, and will continue to take place if we just carry on the status quo over these next 400 years.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks