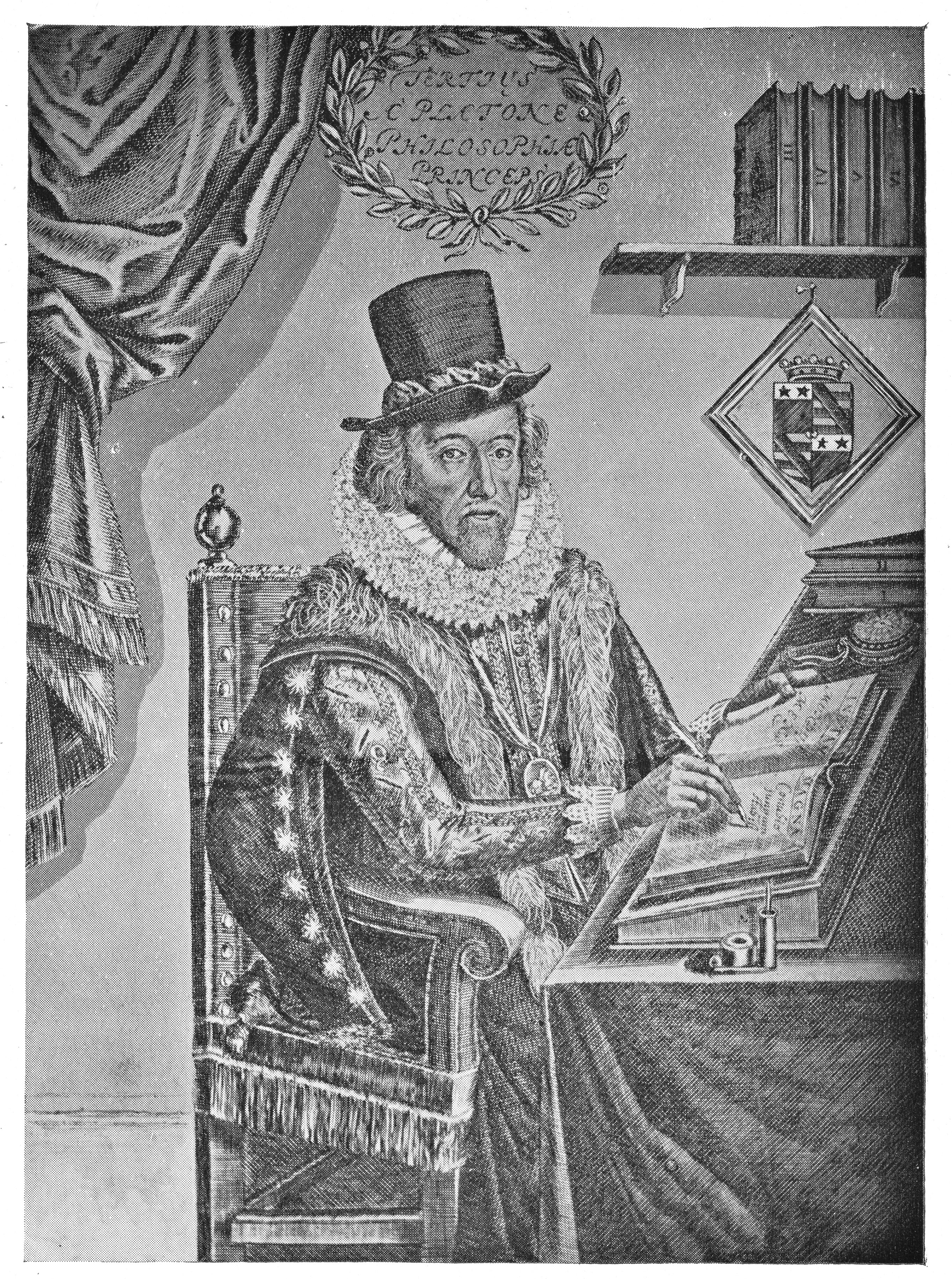

Francis Bacon: Prophetic philosopher or scientific buffoon?

Our series continues with one of the most divisive philosophers of the Renaissance. Was he someone to be admired, or simply a fool?

Few philosophers divide the opinion of commentators as neatly as Francis Bacon (1561–1626). Some have found early manifestations of the very precepts of the Enlightenment in his many writings, while others detect only anti-intellectual propaganda and a defence of the worst kind of religiosity.

Bacon is praised by some as the prophet of modern science, and identified by others as a buffoon whose only attempt at scientific experimentation resulted in his ridiculous death. He is currently reviled by feminists for, among other things, his alleged view that “Mother Nature” is there to be tamed and dominated; and hailed by students of Karl Popper, who find in his writings deep insights into the nature of what would become scientific method.

His life is plausibly viewed from two competing perspectives. From one vantage point, he was a philosopher with a brilliant legal mind, who rose to the height of power before his enemies toppled him with trumped-up charges of corruption. From another, he was an unscrupulous self-publicist and social climber, gaining advantage for himself by any means until he was finally, and justly, ruined by his own greed.

Well connected

He was certainly born with advantageous family connections, which he did try to use. His father was Sir Nicholas Bacon, Lord Keeper of the Great Seal, and his mother, Anne Cooke, was the sister-in-law of Sir William Cecil, Lord Treasurer. Following his education at Trinity College Cambridge, he was called to the bar and began a successful career in law. He combined this work with politics, joining parliament at the age of 23. He was befriended by the Earl of Essex, who tried to help him by loaning him money and by joining Sir William in lobbying for Bacon’s advancement at court. You can imagine the earl’s dismay when Bacon later successfully prosecuted him for treason on the orders of Queen Elizabeth. Despite Bacon’s loyalty to the Queen – if that’s what it was – and perhaps because of some injudicious remarks made about the government’s taxation policy in a parliamentary debate, Elizabeth chose not to advance him.

Bacon is advocating a methodical interrogation of natural phenomena in pursuit of more and more comprehensive laws, resulting in not just knowledge for its own sake, but power

Bacon learned some sort of lesson from the Queen’s displeasure and did all he could to remain in favour with her successor, James Stuart. James sought the conviction of a prisoner, and thought torture and confession the only way to secure it. Sir Edward Coke, Bacon’s rival, demurred, but Bacon obtained the conviction as instructed. His advancement quickly followed. He was knighted, made Attorney General, Lord Keeper, Lord Chancellor, Baron and finally Viscount St Albans. It is difficult not to wonder about the hidden machinations responsible for Bacon’s stellar promotion. It is this speculation that partly underpins the less charitable views of his life.

In the course of his career, Bacon made enemies who eventually charged him with taking bribes. He admitted doing so, in some cases taking money from defendants in cases he judged, and the episode ruined him. He was fined the staggering sum of £40,000 and sent to the Tower. James eventually remitted the fine, released him from prison, and allowed him to retain his titles, but did not go so far as to pardon him officially. Bacon fled to the country but continued to write and reflect on both the law and science. In perhaps the most unfortunate death in the history of philosophy, the story goes that Bacon ventured outside on a cold winter’s afternoon and stuffed a chicken’s carcass with snow, perhaps experimenting with the notion that cold might preserve it. He contracted bronchitis and died soon after.

During the lean years, when Bacon was out of favour with Elizabeth, he wrote most of the fifty-eight essays for which he is duly remembered. The essays are entertaining and realist, perhaps Machiavellian – some contain advice to government officials on what we now recognize as spin-doctoring. However, it is The Great Instauration, the preface for six uncompleted works which together were intended to outline a programme for the restoration and advancement of human knowledge, for which Bacon is most famous. When Bacon wrote it, natural philosophy, or budding science, was more than a little hit-and-miss. Practitioners sometimes undertook bizarre “experiments” simply to answer their own curiosity, and there was not much distinction between alchemy, magic, and embryonic scientific enquiry. Bacon saw in science, if it was properly understood and undertaken, nothing less than the possibility of understanding the natural world – and, in so doing, becoming master of it.

Idols

In this work, Bacon identifies the most pernicious obstructions (false idols) that stand in the way of an objective study of nature: the idols of the tribe, idols of the cave, idols of the marketplace and idols of the theatre. In each are claims that still echo in the halls of philosophy departments.

The “idols of the tribe” are errors built into us as a species (the tribe of men). Humans see the world through human eyes, and such eyes are no sure guide to the real nature of things. Bacon has in mind not just the view that the senses are somehow fallible, but that humans are drawn into errors of judgement by an inbuilt, animal trust in sensory experience. Here, too, Bacon draws attention to something almost Kantian: that the mind imposes an order on what we see that is not really in the world. We are, Bacon argues, predisposed to order the world in our efforts to make sense of it, and in so doing we forget our active part in the order we find.

The “idols of the cave” are errors we are prone to as individuals, based on our particular preferences and motives. What we notice in the world depends on our background of information: we notice what we are able to recognise and what interests us. One is no good in a dog-identifying contest if one doesn’t much care about who wins, or has no idea what a dog is or looks like. Further, we overemphasise the importance of what we are looking for; what fits in with our aims or favourite prejudices; what slides easily along mental grooves worn with long use. Bacon’s idea is that we are all imprisoned in our own theoretical frameworks, like the prisoners in Plato’s cave, and can be misled by the dim reflections of our own view on things. We end up just preferring a certain familiar view of the world, and it blinds us to other possibilities. Bacon warns that whatever one “seizes on and dwells upon with peculiar satisfaction is to be held in suspicion”.

The “errors of the marketplace” arise as a result of human interaction, and here Bacon is pointing to problems in language. He has in mind not just loose or ambiguous talk, but the human capacity to talk past another person, with both parties none the wiser. Further, the fact that a word exists for something does not bring that thing into existence, Bacon argues. No matter how much the philosophers might go on about the “prime mover”, we have no evidence for the existence of the thing in the bare fact of our language use.

Bacon’s invective throughout this discussion, it seems, is reserved for the “idols of the theatre”, and here he draws attention to the errors of traditional philosophical systems – no better than theatrical performances as guides to truth. While he takes issue with dogmatists, who merely assert received philosophical opinion, and the superstitious-minded, who use philosophy to ground religion, his target is close to home: empirically minded philosophers, whose methods Bacon hopes to correct. Conclusions based on too few experiments, limited observation, and general failures of classification and method stand in the way of an understanding of the world.

A new method

His corrective is something more than mere enumerative induction – the practice of observing particular instances and inferring a general conclusion based upon them. He writes:

[T]he greatest change I introduce is in the form itself of induction and the judgement made thereby. For the induction of which the logician speaks, which proceeds by simple enumeration, is a puerile thing … the greatest change I introduce is in the form of induction which shall analyse experience and take it to pieces, and by a due process of exclusion and rejection lead to an inevitable conclusion.

Bacon is advocating a methodical interrogation of natural phenomena in pursuit of more and more comprehensive laws, resulting in not just knowledge for its own sake, but power, utility, the control of things, and thus the improvement of human life. It is much more than particular observations ushering in a general conclusion.

Bacon viewed every natural object as an amalgam of a limited number of simple natures or properties. By careful experimentation, one identifies and lists the many circumstances in which all instances of a nature appear (tables of presence), all instances in which a nature does not appear (tables of absence), and all cases involving an increase or decrease in the presence of a nature in the same object (tables of degrees or comparisons). Suppose you are investigating heat, to use Bacon’s example. You might note its presence in boiling water, its absence in ice, and you might see that it decreases as boiling water cools.

On the basis of exhaustive studies of the presence and absence of natures, and comparisons of their varying degrees, one is able to formulate axioms, interpretations, or what we would now recognise as hypotheses, which then guide the choices made in further tests. One has studied the presence and absence of heat in the various states of water, and on the basis of this, one might hypothesise that other liquids behave in a similar manner. What about mercury? The next step is to boil some mercury and continue recording the results. In due course, perhaps after boiling a lot of fluids, it is possible to formulate a general law, say, of the behaviour of heat in liquids. The laws, Bacon argues, form a kind of pyramid of increasing coverage, and understanding and therefore control of things increases.

Of course, there might be a negative result, and the hypothesis itself might be disproved, but this is still valuable. Bacon maintains that there are a limited number of natures and a limited number of false things to say about them. A negative result is in a sense better than a positive one. Discovering instances which support a hypothesis – even a very large number of instances – does not guarantee its truth. However, identifying falsehood amounts to a kind of certainty. True hypotheses have no false consequences, so a negative result is the only way to know for sure that a guess is the wrong one.

This is much more than the haphazard investigations that characterised “natural philosophy” in Bacon’s time: this is recognisable science.

Major works

Quite early on in his career, Francis Bacon declared to the world that he would concern himself with “all knowledge”. He then announced that he, personally, would carry out nothing less than the complete reform and reorganisation of human thought. Left unfinished at his death, Magna Instauratio or The Great Instauration is Bacon’s plan for this monumentally ambitious scheme.

Of the six parts of the work he planned, only two were completed; the other four were left more as synopses than as finished works.

De Dignitate et Augmentis Scientiarum (1623)

Part one of the Instauration, Nine Books on the Dignity and Advancement of Learning, was published in 1623. Essentially a redrafting of his earlier Proficience and Advancement of Learning, the work outlines what Bacon regards as the principle obstacles to learning.

Novum Organon or New Tool (1620)

Contains what Bacon takes to be the methods proper to the interrogation of nature as well as the so-called “idols” or impediments to truth.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments