A shameful echo of a forgotten holocaust: past terror and fresh injustice

March 1997: Robert Fisk meets the people affected by the 1974 Turkish invasion and explores an often forgotten chapter in history

For Gaspar Aghajanian, it is a matter of principle. For his wife Astrid, it all goes back to the day 82 years ago when the Turks piled the starving orphans of Armenia on top of each other in the sand and burned them alive.

“My mother saved me from the fire by pushing me under a pile of corpses,” she says. “She used to tell me afterwards that when she heard the screams of the children and saw the flames, it was as if their souls were going up to heaven.”

Astrid is now 83, her husband 85, but their battle – against another generation of Turks – is contained in a thick file of correspondence in their bungalow home in Shoreham-on-Sea, West Sussex.

No one comes well out of those fading letters and cuttings; neither the Turkish authorities in Cyprus who refused to compensate the Aghajanians for the property looted from their home after the 1974 Turkish invasion – on the grounds that they were of Armenian ethnic origin – nor the Foreign Office, which failed to persuade the Turks to pay for their plunder, even though the Aghajanians are full British citizens.

“Deplorable,” is how one Foreign Office letter – from Tim Eggar, then parliamentary under-secretary, described Mr Aghajanian’s situation in 1985. But it went on to admit that his claim would not be met unless there was a political settlement on the island.

At a village one night, my father, who had been deported, came to see us. He told my mother that he thought he was being allowed to say goodbye, that he would be shot with the other men

What the Aghajanians lost in Cyprus – Persian carpets, furniture, an ancient coin and stamp collection, photographs of relatives since massacred, a piano, family letters and a large library of valuable books – would only amount to a few thousand pounds. The Turks originally tried to prevent the couple from receiving compensation for their retirement home in northern Cyprus – failing only because Mr Aghajanian was paid for the property before the Turks discovered that he was Armenian. But for Astrid and Gaspar – their families’ refugees from the Turks twice in the same century – the refusal to compensate them for their possessions remains a mark of indignity and shame.

Their story explains all. Astrid’s grandfather, grandmother and uncle were shot dead at the start of the 1915 holocaust against the Armenians, the Turkish massacre that killed at least a million and a half Armenians in what is now Turkey and Syria. Astrid retains faint memories of the long trek over the desert which the women and children were forced to make by Turkish police officers – robbed, raped, starved and burned to death across hundreds of miles of sand.

“At a village one night, my father, who had been deported, came to see us. He told my mother that he thought he was being allowed to say goodbye, that he would be shot with the other men. I remember my mother told me that my father’s last words were: ‘The only way to remember me is to look after Astrid.’ We never saw him again.”

On the long march south, Turks and Kurds attacked the column of women and children, carrying off girls for rape and forced marriages. “My mother would run from one end of the column to the other each time she saw them attacking us,” Astrid says. “My grandmother died along the way. So did my newly born brother Vartkes. We had to leave him by the roadside.

“One day, the Turks said they wanted to collect all the young children and look after them. Some women, who couldn’t feed their children, let them go. Then my mother saw them piling the children on top of each other and setting them on fire. My mother buried herself and me under another pile of dead bodies. Even today, I cannot stand to be in darkness or to be on my own.”

Astrid’s mother, who was only 18, eventually carried her to a Bedouin camp and, after reaching Aleppo – with the help of a Turkish officer – she married her cousin and moved to the newly mandated territory of Palestine, now ruled by the British. In 1942, Astrid met Gaspar, whose own Armenian family had lived in Palestine for generations and who was shortly afterwards to become a magistrate. Fleeing the first Arab-Israeli war in 1948, both took refuge in Jordan – where Gaspar secured British citizenship – and then moved to the still British-administered colony of Cyprus.

Gaspar Aghajanian worked for 22 years for the United States radio-monitoring station on the island, retiring to the bungalow the couple had built for themselves on the newly independent island.

“We never had any problems with the Turkish community,” Astrid remembers. “Our housemaid was Turkish and we got on very well.”

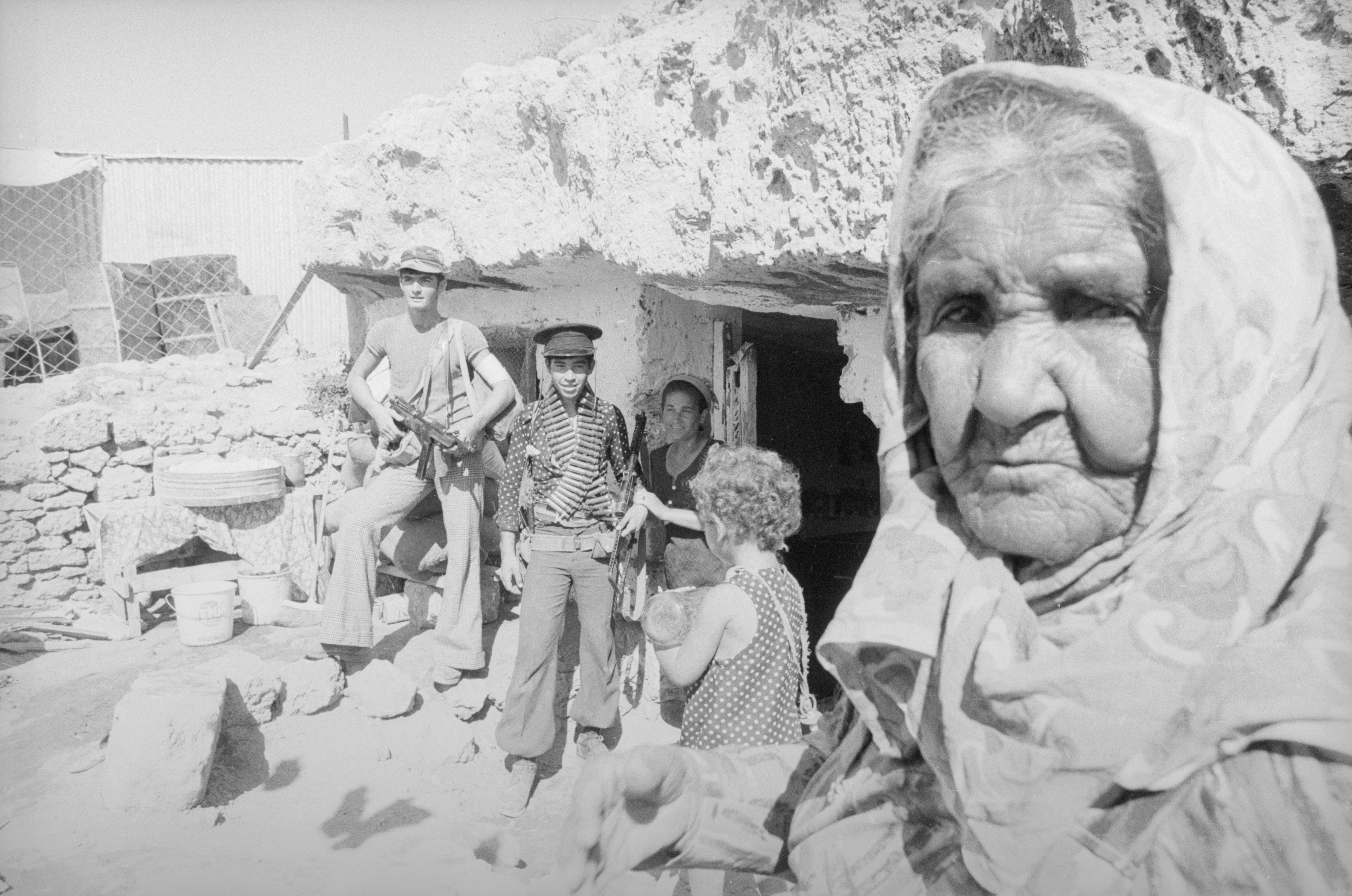

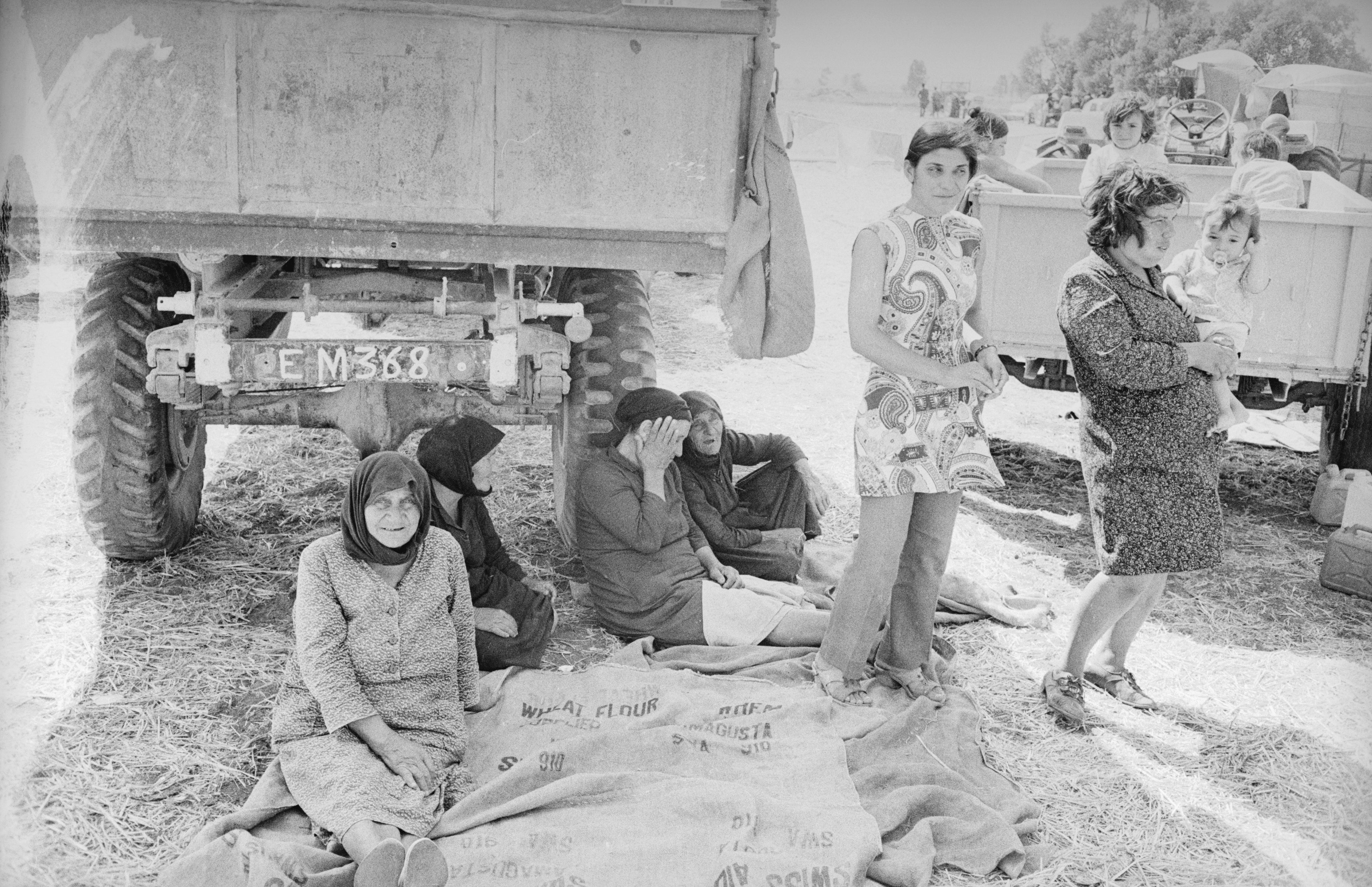

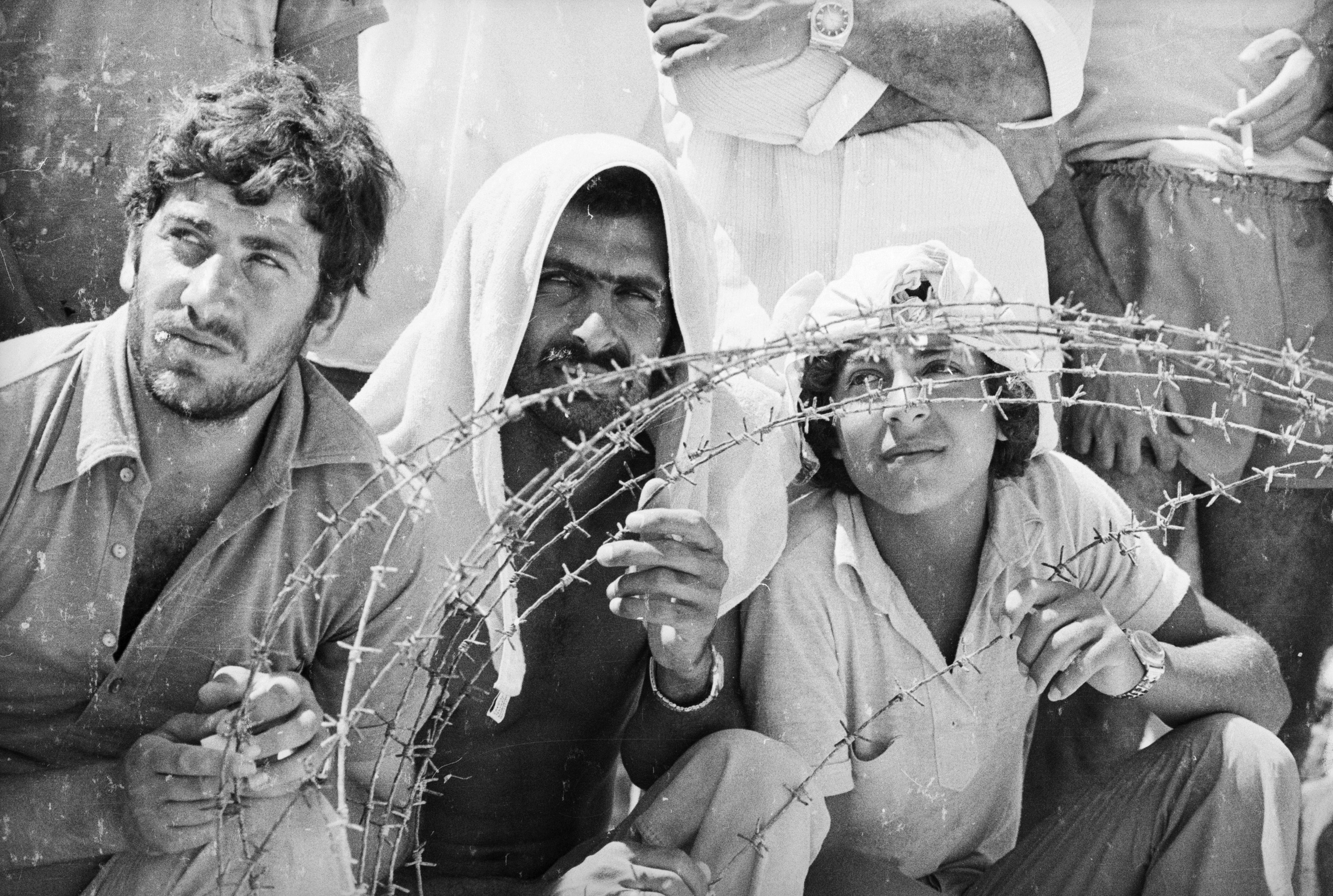

But when the Turks invaded in 1974 – after a Greek-Cypriot coup d’état – the Aghajanians were on the run again from their traditional oppressors.

“We thought at first that the Turks would be disciplined,” Gaspar says. “They were no longer Ottomans – and they were a Nato force. Then we heard of a British couple who’d been beaten up in their home. That decided many of us that we should leave.”

In a convoy of cars – the British actor Edward Woodward was fleeing with them – the Aghajanians made their way to the British sovereign base area at Dhekelia, and thence to Britain.

British residents who managed to return to Turkish-occupied Cyprus reported that the Armenians’ home had been looted. “Front door broken and house searched by army. Contents strewn everywhere...” said one report. The British Government refused to take responsibility for British property. Another letter to the Aghajanians said that “Alas, so far as I can judge, you must regard the contents of your house as entirely lost. The house itself, it seems, has been taken over by one of the newly arrived Turkish police officers, who has apparently cleared it and burned all papers.”

“Gaspar eventually received £15,000 for the house. But when he demanded compensation for the couple’s possessions, he discovered from the Foreign Office – in the words of Tim Eggar’s letter – that “the Turkish Cypriot authorities had... enacted ‘legislation’ to exclude claims made by those persons who were deemed to have Greek or Greek- Cypriot connections. They have now extended this exclusion to cover claims by persons deemed to be of Armenian descent.”

“We were never Greek Cypriots and never asked for Greek-Cypriot passports,” Gaspar Aghajanian says. “We were full British citizens but we were refused compensation on grounds of our ethnic background. And nothing has been done to correct this disgraceful state of affairs.”

When he noticed in 1990 that Margaret Thatcher was to visit Turkey for ceremonies marking the battle of Gallipoli – on the very day that commemorates the start of the Armenian holocaust by the Turks – Mr Aghajanian wrote to his MP, Richard Luce, to complain.

The British Government, came the reply from Francis Maude, then Foreign Office minister of state, “regard the loss of so many lives [in the Armenian massacres] as a tragedy”.

But, he continued, “we have long considered that it would not be right to raise with, or attribute to, the present Turkish government acts which took place 75 years ago during the time of the Ottoman empire”.

“All of which begs a lot of questions for the elderly Aghajanians. If the British government will not even discuss the Armenian holocaust with the Turks on the grounds that the present Turkish government was not responsible, how come they let the Turks discriminate today against British citizens of Armenian ethnic origin? Is this discrimination not directly linked to the 1915 holocaust? And do not visiting heads of state discuss with the Germans the Nazi Holocaust against the Jews – and compensation for the survivors – without blaming the present German government for the atrocities?

“Our holocaust happened a long time ago,” Astrid says. “It is easy to forget us. And Gaspar still writes his letters. But still the Turks can get away with refusing us compensation because of our ethnic origin – even though we are British.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments