There is so much more to Fellini than ‘La Dolce Vita’

Ahead of the re-release of Fellini’s classic film and the launch of a BFI centenary retrospective, Geoffrey Macnab reflects on some of the Italian maestro’s more overlooked works

It is understandable that the BFI’s two-month, UK-wide “centenary” retrospective of Federico Fellini (1920-1993) is opening with the Italian director’s most famous film. Mention Fellini and the image that still springs most readily to mind is of Swedish actress Anita Ekberg as the movie star, Sylvia Rank, in her strapless black dress, looking like a goddess from a Botticelli painting, as she takes an impromptu shower under the waters of the Trevi Fountain in Rome in La Dolce Vita (1960).

The BFI’s marketing for the season emphasises the “exuberantly playful” nature of Fellini’s filmmaking. However, it is worth remembering what happens after Sylvia and her consort for the evening, Marcello (Marcello Mastroianni), come out of the fountain. When they return to her hotel, she is slapped by her drunken, angry fiance, Robert (Lex Barker). Once she retreats tearfully into the hotel, Robert then blithely beats up Marcello. The scene is witnessed by Marcello’s friend, the vulture-like photographer Paparazzo (Walter Santesso), who, of course, doesn’t intervene.

La Dolce Vita leaves a strangely sour taste. Alongside its scenes of reckless hedonism, it is full of squalor, suffering and disillusionment. Characters take drug overdoses or kill their own children. Its jaded pleasure seekers risk seeming very condescending towards the working-class Romans whose lives occasionally intersect with their own. In one uncomfortable early scene, Marcello and an upper-class woman he has met at a nightclub pick up a prostitute and drive her home. Her apartment is squalid. She has to put down planks so they can walk across its flooded floor. She prepares coffee for them while they make love in the one dry room. If they are aware they are exploiting her hospitality, they don’t show it.

For all the charm of Mastroianni’s performance, Marcello isn’t a sympathetic protagonist. A gossip columnist who aspires to be a serious writer, he gives the impression of looking in at events in his own life, as if he is an observer rather than a participant. He is narcissistic and aloof.

Fellini won the Palme D’Or in Cannes for La Dolce Vita. It quickly became, and has remained, his most celebrated film. Its title has long since passed into common usage. The movie also played its part in the evolution of long lens celebrity journalism. Paparazzo’s name was given to the real-life photographers who were even more intrusive and ruthless than him in their pursuit of pictures of film stars and aristocrats. Fellini was spat on. His film was attacked by the Vatican’s newspaper as an “incitement to evil crime and vice”. It was also a huge box office hit in Italy and abroad. From then on, the director was one of those chosen few whose name was instantly recognisable to anyone with even a passing interest in cinema.

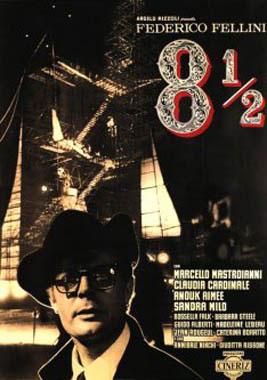

After La Dolce Vita, Fellini continued to make remarkable films. 8 1/2 (1963), starring Mastroianni as Guido Anselmi, a Fellini-like director struggling for inspiration, is considered by insiders as one of the best ever films about filmmaking. Martin Scorsese, in his obituary for Fellini, bracketed it with Citizen Kane as “one of the great landmarks in movies” and wrote about how closely he, as a young film student at New York University, modelled himself on Guido.

Amacord (1973), Fellini’s magical realist evocation of his childhood in the 1930s, is acclaimed by some as a masterpiece. According to Vincent Canby in The New York Times, it is his “most marvellous film”. Fellini’s Casanova (1976), starring Donald Sutherland as the libertine, has its fervent champions as do films like Roma (1972) and his Petronius adaptation, Satyricon (1969). Nonetheless, a persuasive argument can be made that Fellini’s most personal and most affecting work was done before La Dolce Vita – and before his name became an adjective. “Felliniesque” is now used as a matter of course to describe films with a comic, wistful extravagance, in which clowning and melancholy march hand in hand.

There is a rawness to the director’s early features simply not found in his increasingly indulgent and self-parodic later movies. I Vitelloni (1953), Fellini’s second feature, is one of the greatest coming-of-age films. Set in a small Italian seaside town just after the war, it is about a group of young male friends trying and failing to come to terms with adult life in a provincial backwater. They’re wild and charismatic but they’re also delinquents without either drive or responsibility. Gradually, through the eyes of the only one who manages to escape, we learn just how empty their lives are.

“For a young man in Rimini, the life was inert, provincial, opaque, dull, without cultural stimulation of any kind. Every night was the same night,” Fellini later told author Charlotte Chandler of his adolescence in the Adriatic resort town. He left Rimini when he was still a teenager, moving permanently to Rome, the city with which he is now indelibly associated, in 1939. I Vitelloni captures both his nostalgia for the world he left behind and his relief that he was able to get away. “When I left Rimini, I thought my friends would be envious because i was leaving, but far from it. They were perplexed. They didn’t feel the drive to leave that I did,” he later observed.

La Strada (1954) tugs on the heart strings precisely because of its pared down quality. It’s the story of a travelling strongman, Zampano (Anthony Quinn), who recruits Gelsomina (played by Fellini’s wife Giulietta Masina) to accompany him on the road. She is a naive, sweet-natured young woman from an impoverished background. He is a brute. Zampano trains her up to perform in clown costume as his assistant, His pet trick is bursting the metal chains he coils around his midriff simply by expanding his chest. Zampano treats Gelsomina abominably and yet she stays loyal to him.

“La Strada is about loneliness and how solitude can be ended when one person makes a profound link to another. The man and woman who find this bond may sometimes be the least likely, on the surface, and yet the bond is in the depth of their souls,” Fellini later told one of his biographers.

Fellini’s producers had initially protested against his decision to cast the then unknown Masina. However, she is a superb actress with big, sad eyes and a sense of comic timing which rivals that of Chaplin. The third protagonist is the circus clown Il Matto (Richard Basehart), who has past history with Zampano and loves to taunt him. These three have a destructive effect on each others’ lives. Unlike in La Dolce Vita, there are no helicopters, open top sports cars, orgies, stripteases or nightclub scenes here. The film takes place on dusty roads or in the small communities where Zampano puts on his makeshift performances.

Taking his cue from the neo-realist films of his mentor Roberto Rossellini, Fellini fills La Strada with shots of scruffy kids who hover in the background as the increasingly tragic events unfold. He elicits superb performances from his American actors, Quinn and Basehart, neither of whom could speak Italian. The director himself couldn’t speak much English. “Everyone played in his own or her own language and Fellini worked in gesture and mime,” his biographer John Baxter explained the strained but ultimately successful means of communication used on set.

The performances were equally striking in Fellini’s next (strangely underrated) film, Il Bidone (1955), in which Broderick Crawford, famous for as the corrupt politician in All the King’s Men (1949), stars alongside Basehart. They play petty swindlers who dress up in priests’ garb and rip off poor farmers with an elaborate scam involving buried treasure on their land. Crawford had a drink problem but Fellini didn’t see that as an issue. “He (Crawford) was mostly sober during the shooting,” the director later recalled. “Conveniently, when he wasn’t, it turned out to be appropriate for the particular scene.” Crawford’s occasional hangovers added to his character’s furtive quality and sense of guilt at his own dastardly behaviour.

Masina, who played Basehart’s long-suffering wife in Il Bidone, had had a small role in the director’s debut feature, The White Sheik (1952), as the kind hearted prostitute, Cabiria. Fellini went on to make an entire feature, Nights of Cabiria (1957), about the same character. This is one of his finest films – and is very different in tone to La Dolce Vita and his subsequent movies. Rather than caricaturing the prostitute and treating her as an exotic outsider who can show some world-weary city slicker, played by Marcello Mastroianni, life on the other side of the tracks, he tells the story from her point of view. She is a fighter who always bounces back with a cartoonish resilience, whatever fresh misfortune befalls her. “She’s got nine lives, like a cat,” it is said of her. Like her character in La Strada, she keeps her wide-eyed innocence in spite of the corruption and squalor surrounding her.

After La Dolce Vita, Fellini’s films became increasingly... Felliniesque, and not always to their own advantage. It would be absurd to suggest his preoccupations and filmmaking style changed the moment Anita Ekberg stepped into the fountain. Many of the same type of characters and situations are found in the earlier films too. The difference, though, is the lack of bombast and self-consciousness. In their simplicity, features like La Strada and Nights of Cabiria have a directness and pathos that his later movies, for all their fireworks and histrionics, and for all those familiar “Felliniesque” bells and whistles, often lacked.

La Dolce Vita is re-released on 3 January. The BFI’s centenary Fellini retrospective runs throughout January and February

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments