Why a year of penny pinching will help achieve our eco aims

But only if the four-year-old can reach the light switches, says Kate Hughes

Christ alive. Could you all just turn the lights off after you leave a room?” I shout down the stairs. “It’s like Blackpool Illuminations up here,” I mutter as I stamp around making my point felt through the floorboards.

I sound like my dad. Actually, no, I don’t think my dad or my mum ever said anything like that. I sound like a sitcom parent. “Am I really the only person who can flick a switch in this house?”

Maybe there are uber households out there whose angelic inhabitants always eat with their mouths closed, use a handkerchief instead of their sleeve and always, always turn the lights off when they leave a room. And that’s just the adults.

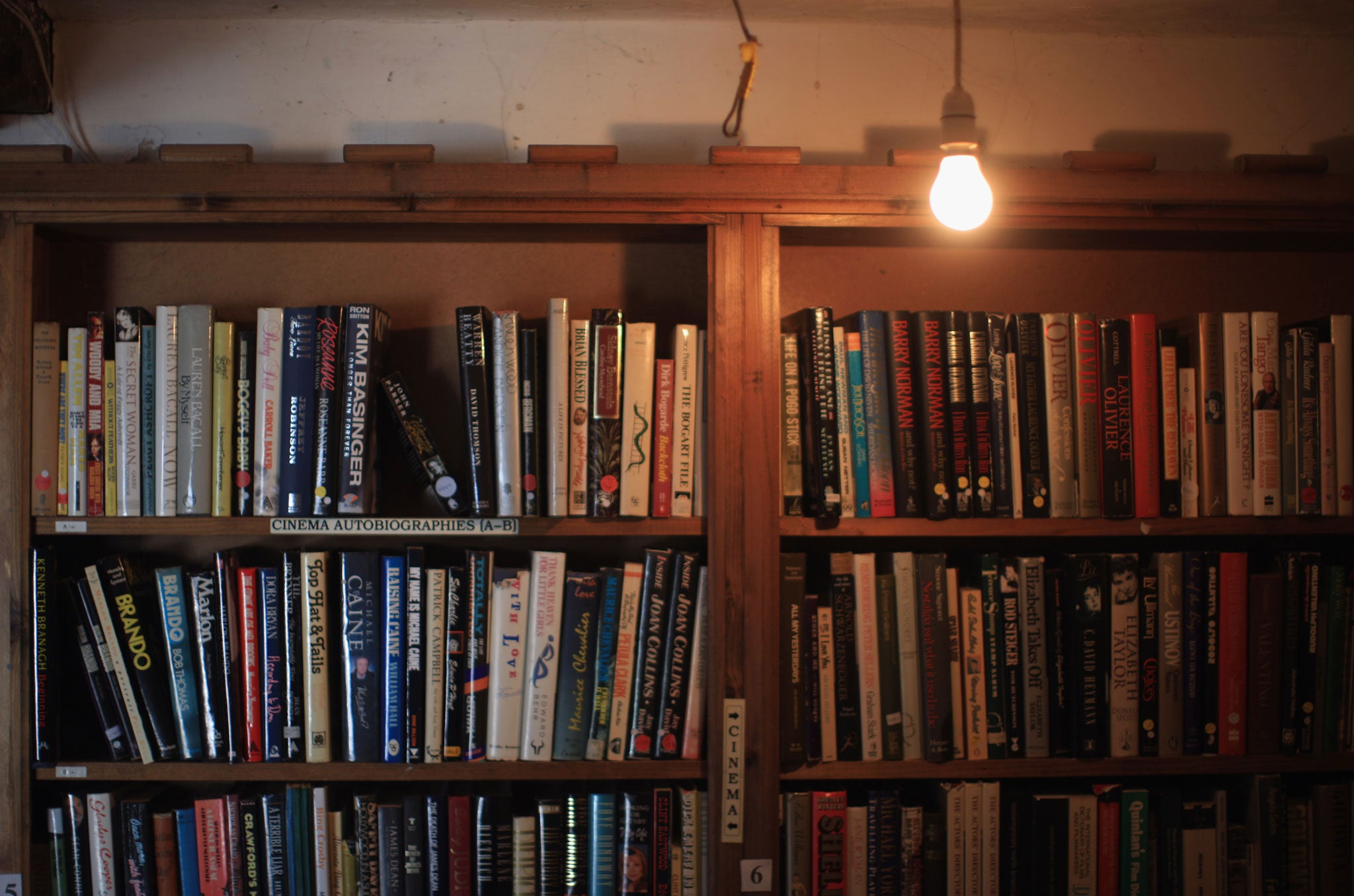

None of them live in our house. Which is admittedly a bit harsh on the small one, who can’t even reach the switches yet. He resorts to precariously piling books against the skirting board, stretching up even as they’re slipping out from underneath him.

I must have banged on about the lights, and the heating, and the perils of standby every day over Christmas and new year.

At this stage in proceedings, I’m boring myself, especially as we’ve now been stuck in Covid isolation for a shade under two weeks. But I’m only going to ramp it up because I know what’s coming – a massive hike in energy bills thanks to wholesale prices and a series of other unfathomably interconnected global circumstances.

Despite new efforts to soften a £2,000-a-year cost, the chances are households like ours are looking at up to a 40 per cent increase. Then there’s everything else that’s set to rise thanks to creeping inflation.

It makes sense that when the cost of something rises, you use less of it. (Particularly if there isn’t a spare £10,000 – and then some – to install a heat pump and the extensive insulation required to make it anything but financially pointless.)

You value the resource more. You waste less. It’s basic book balancing. But you try talking economics – domestic or otherwise – with a four-year-old. Nothing doing.

This year is going to be a more expensive one, for all of us without exception, even before we start adding in the latest, startling debt figures. This time last year we were revelling in having just paid off a cool £915m from our credit card bills. This time around we’ve added that much back into the mix of our financial woes.

In other words, there’s no way I’m the only person turning things off at the wall with renewed vigour as they eye the smart meter. I’m already looking forward to the day the heating gets turned off.

I’m quietly optimistic about the new money and carbon-saving habits we’re on the brink of forming this year. Especially if the little one manages a growth spurt before the weather turns.

There’s another reason this year might be the one we finally shake off the notion that being more environmentally oriented is more expensive than “real life” – as if our current approach to overconsumption is anything other than a failed 60-year experiment.

Yes, this year is going to be tougher. And when demands on our money and time and other resources are cut back to the bone, there’s no doubt our immediate needs, rather than any lofty ambitions to help save the planet, come first.

Research carried out by the Centre for Climate Change and Social Transformations at the University of Bath showed that during the financial crash of 2008-9, climate change crashed out of our list of priorities almost as rapidly as hedge fund managers started buying up bullion, canned food and remote estates in Scotland.

But by the time Covid struck, it wasn’t budging. Even while we battled, weary with the repetition of it all, through the last, full UK-wide lockdown, almost 70 per cent of us said the government would be failing the people of Britain if it did not act now to combat climate change.

Around 40 per cent directly linked the economic recovery from the pandemic with climate change action.

We’re also building on behaviours we’ve picked up in response to that other existential crisis, like keeping food out of the bin and buying things we really need rather than shopping for fun. All of which sounds a lot like several robust ways to save money too.

Now I only have to get the rabble at home to make the link, even the small one. Even when I’m not making my sentiments felt in no uncertain terms by way of a staircase.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks