What covering four inaugurations has taught me about the ‘greatest democracy’ on earth

2020 was not the first time America endured a 'disputed' election, writes Andrew Buncombe

It feels like it was suggested just yesterday.

Given you’re moving to America and will be writing about this man for the next four years, shouldn’t you go and cover his inauguration?

The man was George W Bush, and The Independent's foreign desk suggested that I to fly from London to Washington DC for a week, and be there to write about his swearing-in

It may feel like yesterday, but it was actually January 2001, and the nation had just endured a disputed election, and what at the time felt like a political knife-fight.

Al Gore had won the popular vote by around 500,000, but the electoral college contest had come down to Florida, where there were arguments about a recount, which votes to be recounted, and which to be discarded. For 36 days the US felt as if it it were in suspended animation, until a conservative majority on the Supreme Court ruled in Mr Bush’s favour, and he became the 43rd president, on the basis of fewer than 600 votes.

Twenty years ago, the prize of the presidency was no less great. But the dispute surrounding the outcome felt much healthier than the one in 2020. For one thing, the Republicans’ legal team was led by the gentlemanly figure of James Baker, rather than a wild Rudy Giuliani. Another difference, was that both sides were speaking to each other.

Nevertheless, on the streets of the nation’s capital that day - oddly, inauguration fell on a Saturday - there were plenty of people unhappy that Mr Bush was about to become their president.

Last month, there were far fewer members of the public than at previous inaugurations, the result of the Covid pandemic, and the massive security operation set in motion after the riots on 6 January, when thousands of Trump supporter stormed the Capitol as a joint session of Congress was set to affirm the election of Joe Biden.

And when the swearing in of Mr Biden was done, there were none of the parties and celebrations that typically accompany such an event. Rather, the most frequently felt emotion was one of relief, not simply the reaction of people in a strongly Democratic city that disliked Mr Trump, but that the transfer of power had been completed, without further violence.

What does one learn about a country covering four inaugurations? Mr Bush in 2001 and 2004, Mr Trump in 2017 and Mr Biden last month.

Perhaps, most tellingly, is that many Americans still believe in a sense of exceptionalism, that their nation has been uniquely blessed by God, and is the “greatest democracy” on earth.

You can tell people there are elections in places such as France and Britain, and point out that India is a vaster democracy, but one gets the sense that while people smile and nod, they don’t really agree. (In truth, there was probably a little less swagger, and more anxiety more recently, after Trump threatened the vaunted peaceful transition of power.)

You also learn that on these days, the messages delivered by the new incumbent can send a clear sign of how they hope to govern. Back in 2001, nobody might have predicted how Mr Bush would be shaped by the events of 9/11, but it was central to his 2004 inaugural address.

“At this second gathering, our duties are defined not by the words I use, but by the history we have seen together,” he said. “We have seen our vulnerability - and we have seen its deepest source. For as long as whole regions of the world simmer in resentment and tyranny - prone to ideologies that feed hatred and excuse murder - violence will gather, and multiply in destructive power, and cross the most defended borders, and raise a mortal threat.”

I was living and working in India for both of Barack Obama’s inaugurations, but tuned in to be impressed by the scale of his ambition, telling America and the world “we know that our patchwork heritage is a strength, not a weakness. We are a nation of Christians and Muslims, Jews and Hindus, and non-believers. We are shaped by every language and culture, drawn from every end of this earth.”

In 2017, I was stuck in a crowd opposite the National Archives on Constitution Ave, who booed at the loudspeakers as Mr Trump claimed America had just endured years of “carnage”.

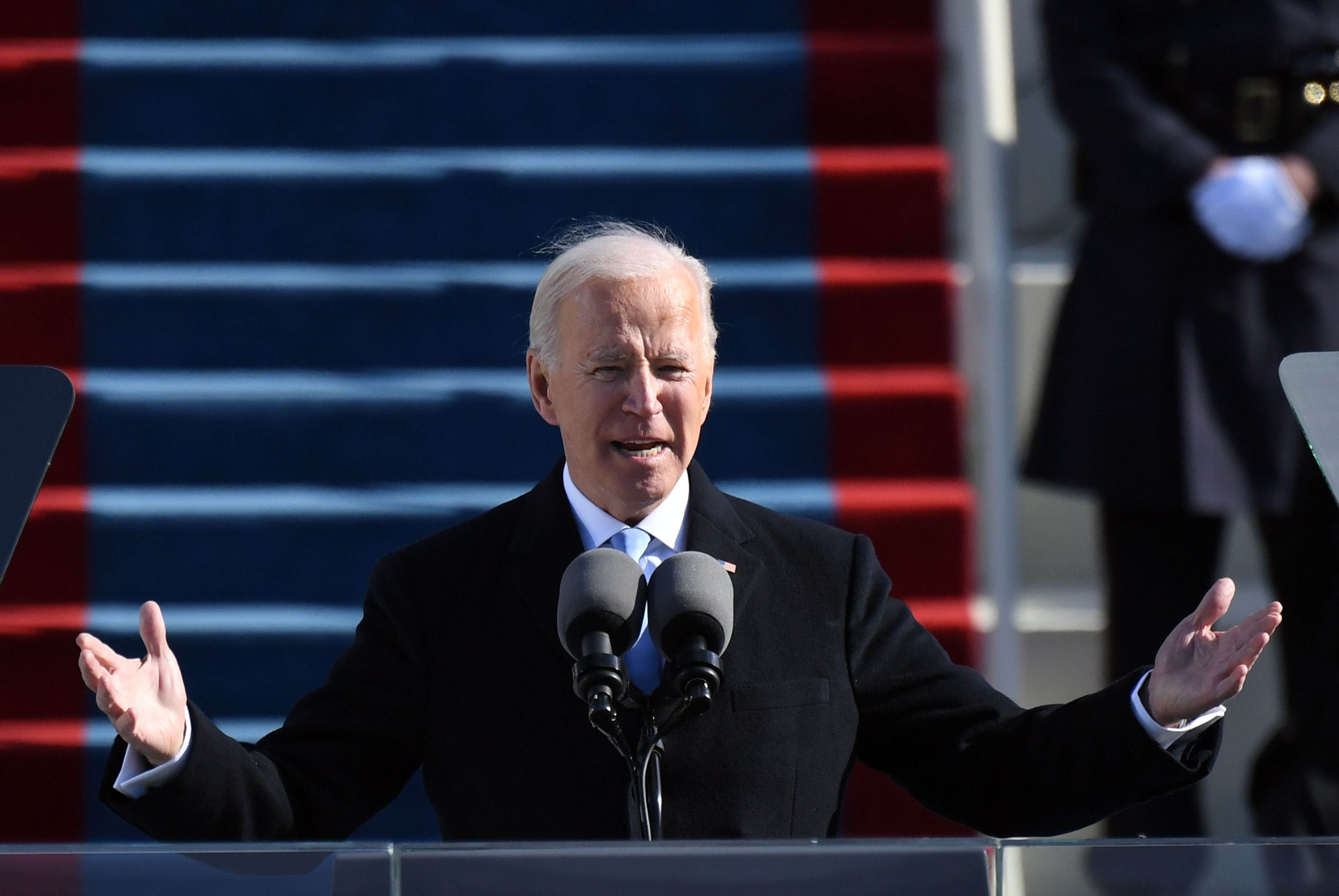

This year, after speaking to some of the handful of members of the public attending the event, I made it back in front of a television screen to hear Mr Biden seek to reach across the political aisle and find unity.

“This is democracy’s day. A day of history and hope of renewal and resolve through a crucible for the ages,” he said. “America has been tested anew and America has risen to the challenge. Today, we celebrate the triumph not of a candidate, but of a cause, the cause of democracy.”

And what about the journalism, and the challenge of covering a major story and filing your story in a timely manner?

Well, lots remains the same. Deadlines are still a menace, whether one is is scrambling to file by 1pm DC time on a Saturday for the print cut-off for the Independent on Sunday, or putting together something thoughtful and comprehensive for the The Independent website. The adrenaline helps of course, as does the coffee. Also the same is that sense of quiet satisfaction when the story is done and filed, and in the hands of the editors.

Most of all, it is still amazing fun. A huge, massive privilege, no doubt, but also tremendous fun.

Yours sincerely,

Andrew Buncombe

Chief US Correspondent

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments