The paradox of Wonder Woman: Looking back on 80 years of the complicated feminist icon

The superhero is both a symbol of female empowerment and an S&M fantasy figure who has inspired lowbrow TV series and very highbrow academic books. As Wonder Woman 1984 arrives in cinemas, Geoffrey Macnab looks at why she is such a divisive figure

Who is this woman? Where does she come from?” a TV news anchor asks in awed bewilderment early on in Wonder Woman 1984 (out this week). The Amazon princess (Gal Gadot) has just rescued children and parents caught up in the mayhem when a jewellery heist in a shopping mall goes wrong. Dressed in her trademark outfit – red boots, blue miniskirt, red top and gold tiara – she leaps from floor to floor of the mall, using her lasso to tie up the hapless thieves.

Wonder Woman may dress flamboyantly and perform mind-boggling, gravity-defying feats of courage but she doesn’t hog the limelight. She uses her bangles to disable surveillance cameras and keep her image out of the media. And the moment her kick-ass stunts are over, she retreats to her day job as a quiet, soberly clothed anthropologist at the Smithsonian Museum.

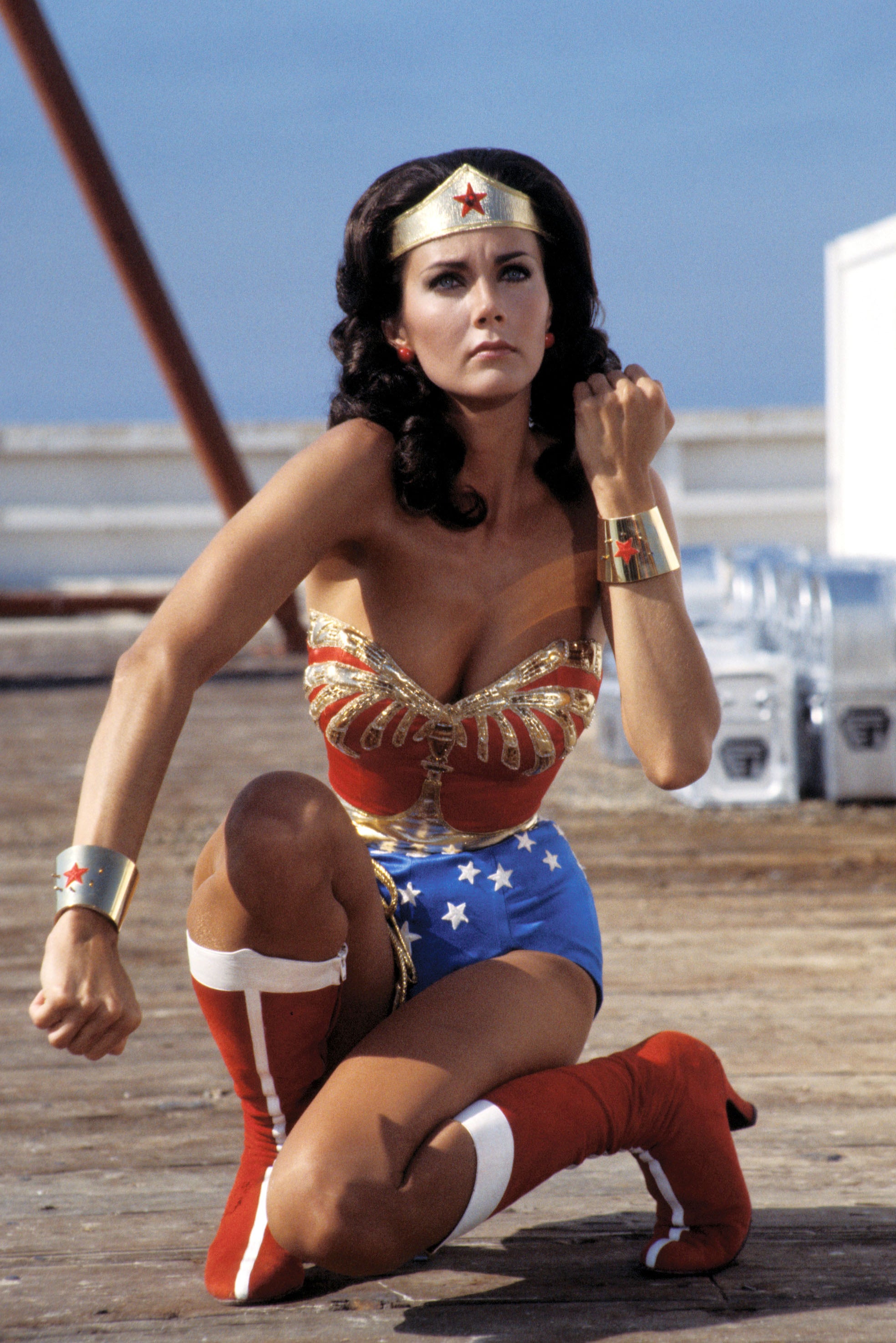

Like the anchorman, audiences may also be scratching their heads at just who Wonder Woman (aka Princess Diana or Diana Prince) actually is and what she represents today. Depending on your vantage point, she is either a family-friendly heroine, a subversive figure of sexual fascination or a symbol of high kitsch. Next year marks her 80th anniversary. She now has a second feature film under her spangled belt to add to the 1970s series starring Lynda Carter, as well as the shorts, TV movies and the many comics in which she has featured.

Look through the various scholarly articles and fan tributes about the character and what you find is contradiction. Some cite her as the “ultimate feminist icon”. Others, though, decry the “enduring racism of Wonder Woman”, drawing attention to the stereotyping in some of the early comics. They wonder, as one sceptic puts it, “What is powerful about a woman running around in a bathing suit?”

At the end of a disastrous, pandemic-affected year for Hollywood, Wonder Woman is being looked to as a potential saviour of global cinema – but that may be a task beyond even her formidable powers. Her distributor Warner Bros has caused consternation among film lovers with its “bombshell” decision earlier this month to release all its 2021 films on US streaming service HBO Max. However, the company is still trying hard to get Wonder Woman 1984 onto the big screen wherever it can. In the UK, the theatrical release has continued this week in spite of large parts the country (including London) moving into tier 3, meaning many theatres are now closed.

When cinemas reopened in Saudi Arabia in 2018 after a 35-year hiatus, the US studios cited Wonder Woman as a character who might help to change attitudes toward gender and free speech. Parrying accusations that it was wrong to be showing their work in a country with such a terrible record on women’s rights, they argued it was beneficial for local audiences to be “seeing women superheroes”. That is why she is on screens in Riyadh this week.

As Wonder Woman dominates showbiz headlines everywhere, one name not always remembered is that of William Moulton Marston (1893-1947), the Ivy League psychology professor and inventor of the lie detector machine who created her in 1941.

Academic and journalist Jill Lepore wrote a fascinating book in 2014, The Secret History of Wonder Woman, on the bizarre origins of the world’s most famous female superhero. Lepore’s frame of reference was huge. She looked in depth at how philosophy, feminism, birth control, Greenwich Village radicalism and the work of social reformers like English writer Havelock Ellis all inspired Marston.

“Frankly, Wonder Woman is psychological propaganda for the new type of woman who should, I believe, rule the world,” the professor turned comic book creator proclaimed.

Lepore places Wonder Woman “not only within the history of comic books and superheroes but also at the very centre of the histories of science, law and politics”. Whereas Batman and Superman were seen in the war years as gung-ho and even fascistic figures, she was always on the side of peace, harmony and women’s rights.

Other highbrow admirers are equally convinced of her cultural importance. “I grew up when there were no female superheroes. Wonder Woman was the first and only one,” American feminist writer and activist Gloria Steinem enthused about her. “She is someone who doesn’t kill her adversaries; she converts them. She has a magic lasso which compels everybody to tell the truth.”

However, from the outset, Wonder Woman was also dogged by controversy. Prudish critics complained that she wasn’t “sufficiently dressed”. During congressional hearings into juvenile delinquency, she was accused of “inciting lesbianism”.

Wonder Woman’s creator Marston is as enigmatic as his superhero. On the one hand, he is a progressive, free-thinking idealist with huge intellectual curiosity. On the other, he is a mountebank and a chancer. Lepore details both Marston’s achievements, prime among them his invention of the lie detector, and his various failed business ventures. For reasons not altogether clear, his academic career quickly began to stall. He was polyamorous, living happily with two women, his wife Elizabeth Holloway and one of his former students, Olive Byrne.

“They lived as a threesome, ‘with love making for all,’” writes Lepore, quoting Holloway.

There was sometimes a fourth member of the ménage as well, librarian Marjorie W Huntley. She was intimately involved in the production of the Wonder Woman comics. According to Lepore, Huntley believed in “both suffrage and bondage… in what she called ‘love binding’, the importance of being tied and chained”. Marston shared these interests.

“Dr Marston, Wonder Woman has drawn criticism for being full of depictions of bondage, spanking, torture, homosexuality and other sex perversions. Would you say that is a fair representation of your work?” Marston (Luke Evans) is asked by educational consultant Josette Frank (Connie Britton) at the start of Professor Marston and the Wonder Women (2017), Angela Robinson’s slyly subversive biopic of the Wonder Woman creator.

“I could see how people with a limited understanding of my work could arrive at these simplistic descriptions,” Marston replies, a little defensively, unable fully to deny the charges.

Robinson’s movie, Lepore’s book and another study, Lee Daniels’ Wonder Woman: The Complete History, all look in-depth at the background to the female superhero. Other scholars have drawn attention to Dr Marston’s less attractive qualities. “Marston and artist Harry Peter regularly presented Asian and black people via racist caricatures. They even used the occasional antisemitic depiction,” Noah Berlatsky, author of Wonder Woman: Bondage and Feminism, wrote about him in a 2016 article.

Few origin stories are as rich or surprising as this one, making Wonder Woman 1984’s blandness all the more anticlimactic. None of the tensions or contradictions about its main character that so fascinate the scholars are addressed in any meaningful way. This is a big-budget family movie that tries to appeal to everyone. It is set in the 1980s partly to draw attention to the excesses of the Reagan era (the idea that “you can have it all”) and partly to allow the filmmakers to indulge in pop culture nostalgia. One of the most excruciating scenes is when Diana Prince helps the love of her life, Steve Trevor (Chris Pine), choose the right outfit. He’s a wartime pilot but she makes sure he dresses up as if he is Rob Lowe in a bratpack movie.

All around the world, greedy humans strike Faustian bargains with the sleazy, maniacally grinning arch-villain, Maxwell Lord (Pedro Pascal) and thereby bring ruin on themselves and the planet. With the world teetering on the edge of collapse, Wonder Woman steps up to the plate.

“She is a perfect example of what I believe superheroes are meant to do, which is to show us how to be our better selves and remind us that by doing so, we can create a better world,” writer-director Patty Jenkins says. That, though, makes her sound more like Pippi Longstocking than the brooding, tormented figures we are used to seeing in films about Bruce Wayne or Clark Kent.

Wonder Woman 1984 certainly passes muster as old fashioned matinée entertainment in the Indiana Jones vein. What you won’t find here, though, is any of the twisted humour or perversity that Marston and his collaborators originally brought to Wonder Woman. This is a 12A so you don’t expect her to get up to anything too kinky with her bracelets and lasso but the film could surely have benefited from stepping a little further toward the dark side.

“Who is she?” The new film dodges the question, instead offering us a very wholesome Princess Diana who doesn’t appear to have any hidden depths at all.

Wonder Woman 1984 is out now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments