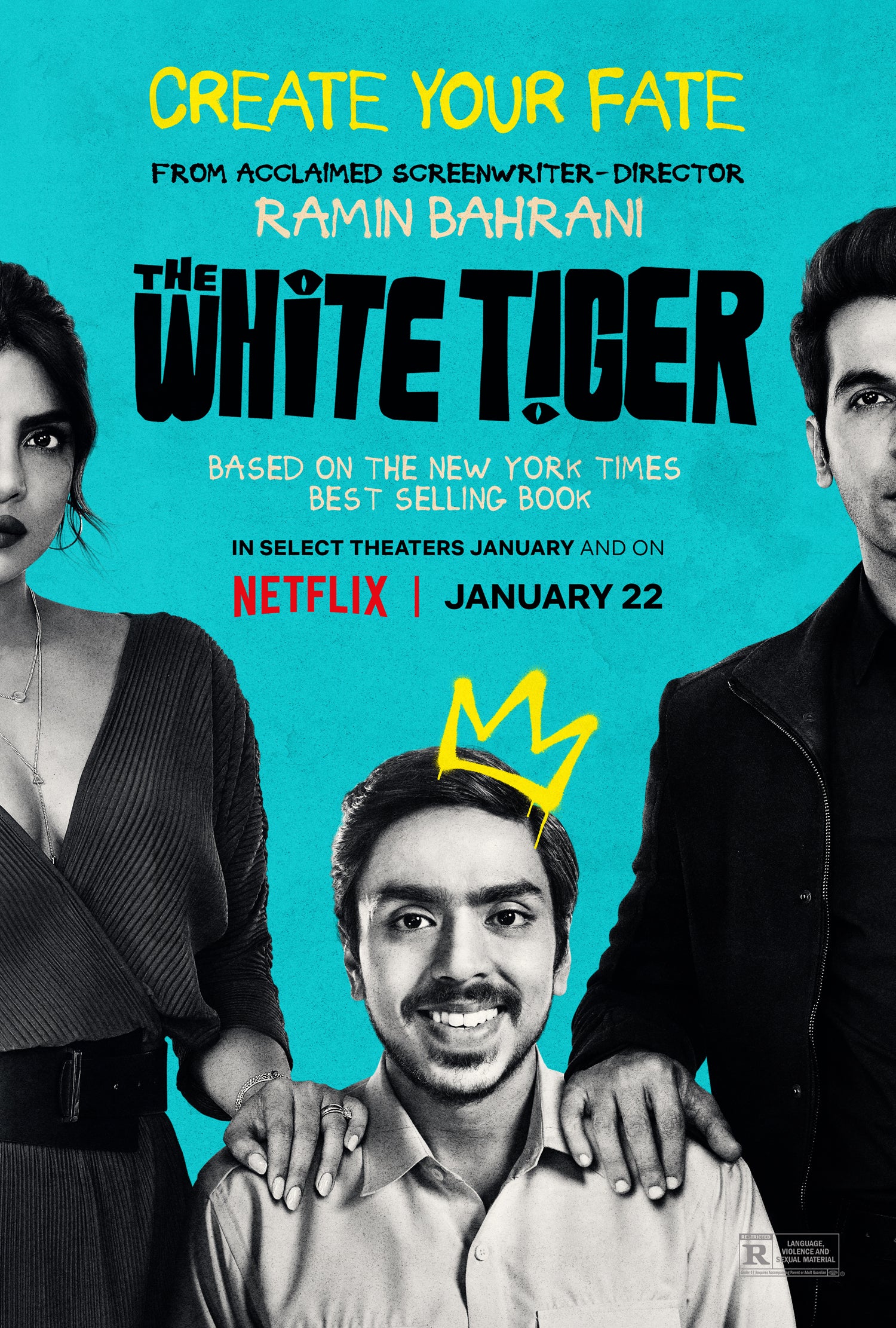

In Netflix’s The White Tiger, there are no heroes or villains

The film adaptation of the 2008 Booker Prize-winning novel about class inequalities in India doesn’t make such binary distinctions about its characters. That’s why it’s just as relevant today, its stars tell Tufayel Ahmed

It’s the century of the brown man and the yellow man, and god save everybody else,” protagonist Balram Halwai audaciously declares in Netflix’s film adaptation of Aravind Adiga’s Booker Prize-winning novel The White Tiger, after making the rare leap from India’s poverty-stricken working class to the wealthy elite. But The White Tiger is no conventional rags-to-riches story, and Balram is not your typical hero.

Central to this blistering depiction of India, directed by Iranian-American filmmaker Ramin Bahrani (Fahrenheit 451, 99 Homes) and the 2008 novel on which it is based, is the theme of stark class inequalities. The haves and have-nots. As Balram – played so strikingly by Indian actor Adarsh Gourav – points out: “In India, there are two kinds of people: those with big bellies and those with small bellies.”

Balram, born into a lower caste of sweetmakers, has an appetite bigger than his belly but remains indentured in a life of servitude like most of the population – what he calls the “rooster coop”, or people conditioned to accept their battery-hen lives with little in the way of upward social mobility. But Balram is not content with his lot in life. He orchestrates a scheme to join the 1 per cent by getting a job as a driver to the American-educated son of a wealthy landlord, and this is where the story diverges from nobly intentioned steal-from-the-rich, feed-the-poor Robin Hood fare. Balram isn’t above going to extreme lengths to escape the rooster coop, resorting to blackmail, theft and murder to become an entrepreneur in his own right. He is, he says, a “white tiger”, a species so rare that it is only born once a century.

Through Balram we embark on a damning crash course in the socioeconomic inequalities experienced by the working class, barely able to make ends meet after paying exorbitant rent and arbitrary fealty demands, and the cesspool of corruption at the top of Indian society – the wealthiest bribing government figures to avoid taxation while simultaneously physically and mentally intimidating the working class to keep their coffers lined.

Fans of Adiga’s searing novel, which caused visceral, angry reaction in India 12 years ago, will be pleased that it is a largely faithful adaptation of his fine book and this tiger has lost none of its bite in translation. Perhaps that's because the director, Iranian-American filmmaker Ramin Bahrani (Fahrenheit 451, 99 Homes), is one of Adiga’s closest friends, dating back to their time at Columbia University in the 1990s, and the person to whom the book is dedicated.

Bahrani read pages from Adiga’s manuscript for The White Tiger four years before it was published and went on to thrill the literary world, including the Booker Prize judging panel. “I was immediately blown away. It’s about serious, hard themes, but it’s told through this leading character with so much wit and sarcasm,” says Bahrani. The director is referring to the immersive narrative device Adiga employs in his book; The White Tiger is told through increasingly absurd, self-aggrandising first-person emails from Balram to another great entrepreneur of import, former Chinese premier Wen Jiabao. In other words, a screed that even Eminem’s Stan might think was too much.

Adding starpower in front of and behind the camera is Priyanka Chopra Jonas, Indian cinema’s most famous global export, who doubles as executive producer – along with Oscar-winning director Ava Duvernay – and actor. Chopra Jonas, an avid reader, discovered Adiga’s novel when it started creating a stir and immediately fell in love with it.

“Sarcasm is one of my favourite languages,” she says, “and it’s so funny and smart and sarcastic. You’re rooting for Balram but you don’t know why … it was just so provocative. It made me uncomfortable but at the same time appreciative of being able to be on the journey.” The White Tiger stayed with Chopra Jonas long after reading it over a decade ago, so, when she heard it was being turned into a movie, “I chased after it. I met Ramin in three different cities in the world [to audition]. I’m glad it worked out,” she laughs.

Chopra Jonas’ Pinky Madam, the American-raised wife of Balram’s new boss, Ashok (played by Bollywood’s reigning leading man, Rajkummar Rao), rouses each time she is on screen. Pinky is often the moral compass by which the inequity of the class system is laid bare. More empathetic towards her chauffeur than her book counterpart, who mocks Balram’s lack of education and pronunciation of “pizza”, Chopra Jonas’ Pinky stirs Balram to aspire to more than being a driver-cum-whipping boy. This results in a powerful scene in which Pinky, increasingly disillusioned by the disparities around her and her in-laws’ treatment of their servants, disintegrates the still-prevalent caste system by which people are arbitrarily placed higher or lower on the societal totempole. “This caste system thing is total bullshit,” Pink tells Balram, recalling how Ashok’s brother disapproved of their marriage because of her own lesser social status.

It’s hard to wrap your head around Balram’s character at the end of the film, but I think that might be a good thing

The scene is sure to stir emotions about caste and social class as complex and impassioned as Adiga’s novel did 12 years ago. Bahrani and Chopra Jonas believe the film’s tackling of class inequalities in India is as relevant today as it was in 2008. They say it also speaks to universal inequalities amplified by the coronavirus pandemic – namely working-class labourers or frontline key workers who have little choice but to continue going to work and face higher risk of infection. In the UK, for example, Public Health England reported last August that Asian or British-Asian nurses, midwives and nursing associates were diagnosed with Covid-19 at twice the rate of their white counterparts. The Office for National Statistics, meanwhile, found in June 2020 that male “elementary” workers – ie construction workers, factory workers and cleaners – faced the highest risk of Covid-related death among men. Covid-related deaths were three-times more likely among men in “elementary” occupations who lived in the most-deprived neighbourhoods.

“I’m glad to have a line in the movie that will spark a debate. It’s uncomfortable, but it’ll spark it,” says Chopra Jonas. “The book was at a time in India when it was the turn of the millennium, India was touted to be the next superpower, the economic freedom – all of that was happening. It was a different time. A very different India than it is now. But, at the same time, the themes are super-relevant to not just Asia, but around the world… it just happens to be based in India. I think the class and socioeconomic disparity that exists in the world right now is rapidly increasing, and it’s the largest that we’ve seen in the history of mankind, actually.”

Bahrani adds: “I feel [it is] relevant here where I live, in New York. In a tragic way, Covid has exacerbated the fault lines of wealth inequality. I see Uber drivers or Seamless [food] delivery people, or a TaskRabbit worker that comes and puts together your Ikea desk – to me they’re all Balram. We were clapping here for first line workers, our EMT workers, and many of them didn’t even have health insurance.”

The White Tiger’s incisive commentary on class inequalities and the parallels to the pandemic-seized society we find ourselves in is all the more significant given that, mere days before this interview, Chopra Jonas was accused by a British tabloid of breaking UK lockdown rules by attending a hair appointment in London, where all salons and barbers are currently closed. Through her spokesperson, Chopra Jonas denied flouting lockdown rules, explaining the salon was opened privately to accommodate the production of the film she is currently shooting in London, Text for You, also starring Celine Dion. Covid-secure film and television productions are permitted to continue in the UK. “The exemption paperwork legally permitting her to be there was provided to the police, and they left satisfied,” said the actor’s spokesperson.

The quasi-controversy adds to the growing discourse around government rules and guidance on the pandemic and how liberally they may or may not apply to the privileged few. Last week, British prime minister Boris Johnson was criticised for a seven-mile bike ride from Whitehall to Stratford, east London, despite giving instructions to the public to “stay local”. And pop star Rita Ora also came under scrutiny for hosting an illegal gathering for 30 friends at a London restaurant last year.

I think the class and socioeconomic disparity that exists in the world right now is rapidly increasing, and it’s the largest that we’ve seen in the history of mankind, actually

Chopra Jonas, Bahrani and Balram actor Adarsh Gourav all consider themselves middle class and all agree that working on The White Tiger, and reflecting on the way that the coronavirus has made clearer disparate social class divides, has made them take stock of their own privilege.

“I’m extremely self-made. Wherever I am is because of my perseverance and hard work. I understand [it]. My parents were military folk and we come from major simplicity,” says Chopra Jonas. “But the simple things [feel like] a lot of privilege. When I grew up, if I got an A in an exam, my dad would get me a Barbie doll. Balram’s sister probably didn’t even know what that was or had a doll. There’s something skewed about the way the world functions. Obviously, we’re not heads of state or lawmakers, so we don’t know how to reconcile it or fix it, but as filmmakers, we can align ourselves with subjects that create a debate.”

Adds Bahrani: “Every time I push a button on my phone and someone brings food to this house, you feel like there’s something wrong in the way the world is working.” The director says he doesn’t know how to “reconcile it” but is “most interested” in films that challenge the socioeconomic status quo. “It is a complex feeling. I’m hoping the film will entertain people and, maybe in the end, you’re going to be left with some questions.”

Lead actor Gourav grew up in Mumbai, far removed from what Adiga’s novel and the movie call the “Darkness” – the India of poverty and inequality. The White Tiger marks Gourav’s breakout film role, having previously appeared in Netflix’s Indian thriller series Leila and as a teenage version of Shah Rukh Khan’s lead character in the moving post-9/11 drama My Name is Khan.

In order to inhabit Balram, the 26-year-old actor says he thrust himself into a more austere life, spending two weeks living anonymously in a small village in Chakan, Pune, in the west of India. “I wanted to have a very undiluted and unbiased experience of living in a village where people could count me as one of them,” he says. After two weeks of village life, Gourav continued his method research with a further two weeks spent working on a food cart in Delhi, again not letting anyone know he was an actor. “I thought it was important for me to work at a place where I didn’t necessarily want to work, but still had to work,” he says, in order to get a sense of Balram’s “feeling of entrapment” in his life. “I was helping to clean plates and keep the place tidy. [The owner] paid me 100 rupees a day [around £1] and I worked 12 hours a day,” he says. “It was really eye-opening to see the lives people lead, and how ignorant we become by being so busy in our own lives and ignoring everything that’s happening around us.”

At one point in his deep, method research, Gourav says he even raised the suspicions of staff at the Delhi hotel he was staying at and was followed. “It was a fancy hotel. It was a strange situation … I used to walk out in the clothes I’d wear to the tea shop and then in the evening would go to the mall to buy my salad in my clothes as Adarsh. They were bewildered.”

In the rich, subversive narrative of The White Tiger, Balram doesn’t earn his fortune as earnestly as working in a tea shop, nor is Chopra Jonas’ Pinky quite the white knight she makes out to be. The strengths of the film lie in the flawed human experiences conveyed – the desperation Balram is driven to, and the sneering ignorance that Pinky and other wealthier characters have towards the working classes. “She’s this fake-woke thing, which is such a, I don’t want to say western, but such an outside-in perspective to a developing economy,” explains Chopra Jonas. “Pinky sits with Balram and is like, ‘I pulled myself out of the circumstances I was born into, why don’t you do it, too? You have to choose what’s good for you!’ [She doesn’t understand] what this vortex of poverty is, and how hard it is to get out of something like that. As an Indian, I understood it. But when I was doing the scene, I had to lean out of my understanding and lean into an American perspective, or [that of] someone who doesn’t understand the smell of what that feels like.”

The take-home moral of The White Tiger can’t neatly be put into words, not least because of the less-than-savoury means by which Balram gets out of the Darkness and the person he has become. Hero or villain? The White Tiger doesn’t make such binary distinctions about its characters, just as in life we are all, by nature, paradoxical creatures capable of warmth and guile in equal measure.

The White Tiger director, Bahrani, says it best: “It’s hard to wrap your head around Balram’s character at the end of the film, but I think that might be a good thing.”

The White Tiger is on Netflix now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks