From Unhinged to Breakdown: Why are filmmakers so drawn to road rage?

Russell Crowe stars as an angry driver seeking revenge in ‘Unhinged’, but it’s just the latest in a long line of road rage movies about people driven to breaking point, says Geoffrey Macnab

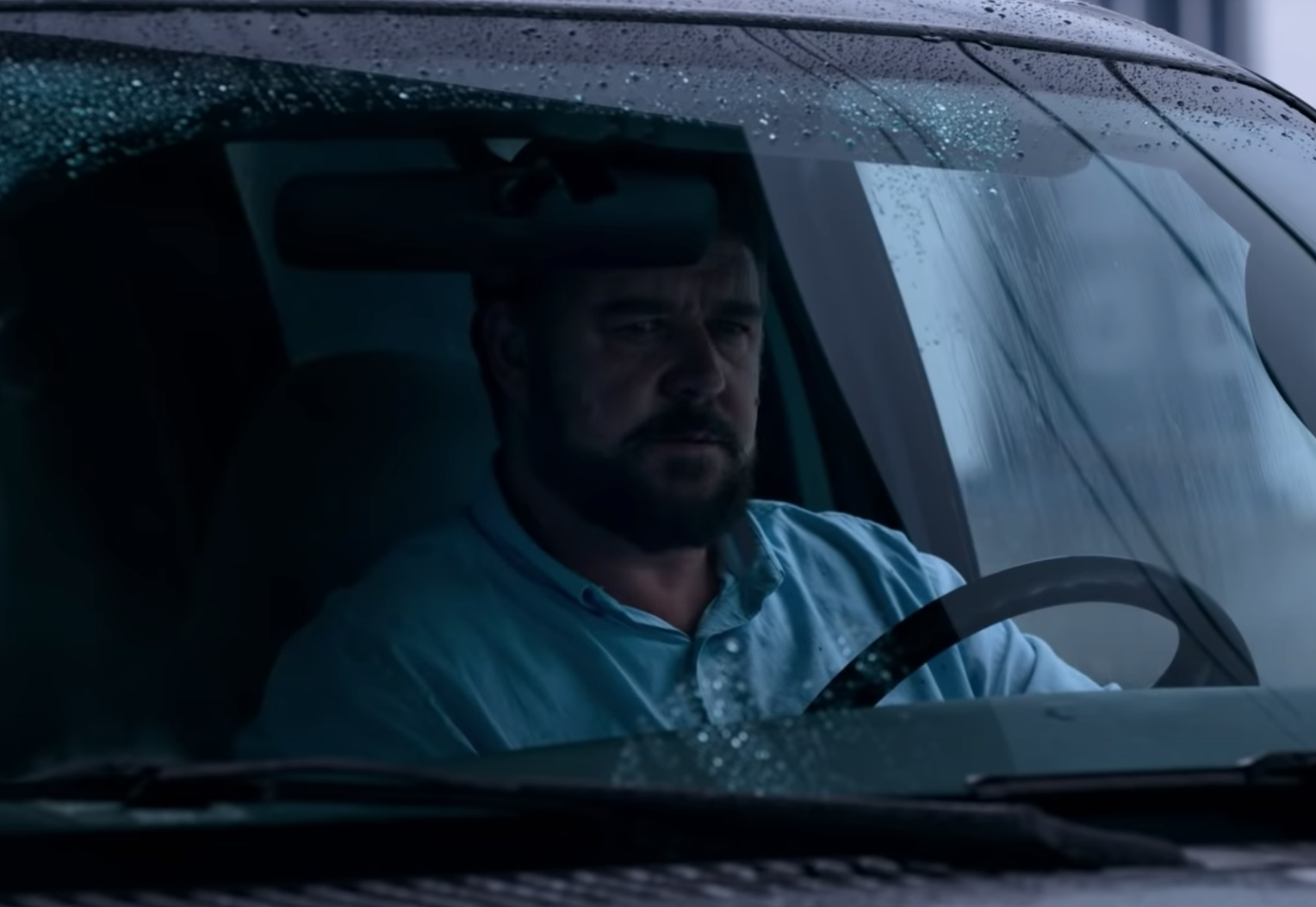

You don’t want to honk your horn at Russell Crowe. That is one of the main lessons gleaned from the trailer for Crowe’s new action film Unhinged, due to be released in US cinemas next month.

Crowe plays “the man”, an overweight driver in a pick-up truck who is having a very bad day. In heavy traffic, Rachel (Caren Pistorius), a young mother stuck behind his vehicle, gets angry that he is holding her up and pushes her horn. He tries to apologise, she doesn’t accept and she certainly won’t apologise to him in turn. That is when he becomes... unhinged. He follows her, steals her phone, and generally tries to ruin her life.

Unhinged, directed by Derrick Borte, is the latest in a long line of road rage movies. Judging by the trailer, it’s a formulaic affair, another by the numbers thriller. Nonetheless, it might be just what is needed to get filmgoers out of their homebound, post-lockdown apathy. US cinema owners are clearly hoping that Unhinged will appeal to audiences who’ve been cooped up for too long, who are suffering from a bad dose of cabin fever and looking for a way to vent their frustrations. Crowe is ostensibly the villain but many are likely to feel a little nagging sympathy for him. This summer’s coronavirus pandemic has left many broiling with the same anger and anxiety that drivers feel when they are caught in a never-ending traffic jam, stuck in their vehicles, and beginning to feel more and more resentful of others around them.

It is instructive to read the RAC’s notes on “road rage”. The RAC claims the term was first coined by US broadcasters in the 1980s in response to a spate of shootings on the highway. However, anyone who has seen Steven Spielberg’s feature debut Duel (1971), originally made for TV, in which a monster truck pursues a businessman (Dennis Weaver) in his car, knows the phenomenon existed long before that.

“It [road rage] is often dismissed as just another part of modern driving, but road rage is a serious problem that can lead to real dangers on the roads,” the RAC advises. “It can be very dangerous. Aggressive, angry motorists not only create an intimidating driving environment on the roads, but their actions can also lead to collisions which can cause casualties and even fatalities.” It starts with rude gestures and verbal insults and then, at least in films on the subject, it escalates.

The RAC notes on how to cope as a victim of this rage and how to avoid becoming a perpetrator are illustrated by an image of a young, affluent looking woman. She is shown sitting behind the wheel of her car with her fist clenched. She is open-mouthed, snarling in fury, and looks more like an actor in a violent genre thriller than someone offering practical advice on road safety to British drivers.

In the 1997 thriller Breakdown, a cop on the desert highway sums up nicely just why filmmakers are so drawn to road rage as a subject. Kurt Russell plays Jeff Taylor, whose car breaks down. Truck driver “Red” Barr (JT Walsh) stops to assist. He agrees to give Jeff’s wife Amy (Kathleen Quinlan) a lift to a diner a few miles down the highway so she can call for help. However, Amy vanishes, and Jeff is convinced the truck driver has abducted her.

“Mr Taylor, I’ve seen it a hundred times. You put two people in a car long enough and they’re going to go at it – lovers, married couples, gay guys. Hell, I’ve seen men dump their women on the side of the road and vice versa,” Sheriff Boyd (Rex Linn) tells the distraught Jeff. Road rage, he is suggesting, isn’t just confined to outsiders. The anger can just as well be directed towards fellow passengers. Something about being inside a vehicle exacerbates tensions that may already exist between friends, lovers, and family members.

Meanwhile, solo drivers feel strangely emboldened. “There’s a degree of separation that happens when we’re each in our cars as well – this can embolden drivers to show much more hostility than they would if they weren’t in the isolation of their own vehicle,” the RAC warns us.

Russell may have played the harassed husband in Breakdown but in Quentin Tarantino’s Deathproof (2007), he is the one causing carnage on the highway. Tarantino casts Russell as a psychotic and misogynistic stunt driver with an appetite for headlong crashes in which glass is shattered and limbs are severed, all filmed in the most fetishistic slow motion.

In American cinema, road movies celebrate freedom and escape. Characters hit the highway on their Harley-Davidsons or in their Mustangs and the opportunities seem endless. In contrast, road rage movies tend to be about confinement, frustration and the extreme narrowing of possibilities.

Joel Schumacher’s Falling Down (1993) begins with one of the great road rage sequences. Michael Douglas, playing William “D-Fens” Foster, is shown sitting in his car. The twitching corner of his mouth is first seen in a huge close-up. Then the camera pulls back to reveal that he is stuck in traffic.

Everything irritates him: the kid in the back seat of the car in front; the woman sloppily putting on her lipstick using her wing mirror; all those witless bumper stickers and those garish car ornaments and teddies; the children in a schoolbus making mischief and throwing paper darts; and the men picking their noses or having conversations on their chunky early model mobile phones. It’s a sweltering day but Foster’s air conditioning isn’t working. Sweat is pouring down his neck. His anger mounts and mounts. Eventually, after a fly pesters him, he loses it. His rage manifests itself not in attacking fellow motorists or blasting away on the car horn but in getting out of the vehicle. He simply abandons the car and walks off across the freeway underpass.

Falling Down was made in LA during the riots of 1992. The film captures the combustible mood in the city at that time. Douglas’s character is the American everyman driven to breaking point. His life is coming apart anyway but being stuck on the freeway hastens the process. Moments later, he is shown assaulting a Korean shopkeeper with a baseball bat because the shopkeeper speaks in broken English and won’t give him change to use the phone. Douglas’s everyman is revealed as a racist psychopath with a deep-seated grudge against the world.

Road rage changes even the most reasonable and seemingly even-tempered types into vengeful, aggressive thugs. In Roger Michell’s Changing Lanes (2002), the warring parties are a brash young lawyer (Ben Affleck) and an insurance salesman (Samuel L Jackson). They’re both driving in New York with court cases to attend. Gavin Banek (Affleck) swerves into Doyle Gipson’s lane (Jackson). After the crash, they are initially civil. Gipson is a recovering alcoholic going through a messy divorce and trying to get joint custody of his kids. He wants to “do this right” and exchange insurance details. Banek, though, is late for court and won’t wait. He abandons Gipson in the rain. The lawyer has lost a vital document at the scene of the accident. The insurance salesman misses the beginning of a crucial divorce hearing.

This is a film in which the rage is delayed until after the protagonists are off the road but it is all the more powerful a result. A very minor accident threatens to derail both men’s lives. Their fury towards each other is unbound.

Recent Dutch film Tailgate (original title Bumperkleef) is about a middle-class family on a road trip who fall foul of a man in a white van. In the film, screening in next week’s Cannes “virtual” market, the father Hans (Jeroen Spitzenberger), an arrogant control freak with a short temper, is driving fast to get home. He becomes annoyed at the van holding him up but antagonises the van driver in the process. Cue the normal scare tactics and high-speed chase scenes as he and his family race for their lives with the van in fast pursuit. As the danger mounts, Hans’s self-confidence crumbles.

Its concept may be second-hand but critics in the Netherlands voted Tailgate as one of the best Dutch films of last year. “In Hans, I enlarged all the bad qualities of myself. His behaviour in traffic is a bit like mine. I also have a problematic ego,” writer-director Lodewijk Crijns told the Dutch press about how he used his own experiences behind the wheel when devising the movie. It’s a revealing observation. Very few of us have robbed banks or been involved in the gunplay and physical violence dramatised in most movie thrillers but almost everyone who has been in a traffic jam or has been cut up by another driver at a set of traffic lights understands road rage.

The best road rage movies tend to be pared down, primal affairs in which evil is shown in the abstract. Drivers find themselves being hunted down by antagonists whose faces they may not even have seen. By tailgating them or blasting a horn at them, these drivers bring retribution on themselves. There isn’t generally much time for characterisation. What matters is the chase and the desperate struggle to stay alive. In Spielberg’s Duel, the truck driver’s face is never shown. As novelist Stephen King wrote of the film, “ultimately, it is the truck itself, with its huge wheels, its dirty windshield like an idiot’s stare, and its somehow hungry bumpers, which becomes the monster ... Duel is a gripping, almost painfully suspenseful rocket ride of a movie”.

The anthropomorphism is deliberate. In his biography of Spielberg, Joseph McBride quotes the director explaining just how he made a battered gasoline tanker look so human. “I had the art director add two tanks to both sides of the doors – they’re hydraulic tanks but you ordinarily wouldn’t have two. They were like the ears of the truck. Then I put dead bugs all over the windshield so you would have a tougher time seeing the driver.”

In Unhinged, Crowe is the star, not his vehicle. Nonetheless, you can’t help but notice that the Australian actor looks as gnarled, bloated, dusty and beaten up by life as the truck in Duel. “He can happen to anyone” is the slogan on the poster, as if the angry driver is a force of nature being unleashed rather than simply a man fallen on hard times. Crowe is unlikely to add to his store of Oscars with the film but the chance to see him at his most explosive may entice viewers back into theatres. With most other blockbusters having their release dates shifted back to the autumn or later, this will be one of the few attractions on offer to American filmgoers this summer. A little road rage may be just what is needed to jolt cinemas out of their longest period of hibernation in living memory.

‘Unhinged’ is due to be released in the US on 10 July

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments