Books of the month: From Sally Rooney’s Beautiful World, Where Are You to Snow Country by Sebastian Faulks

Martin Chilton reviews six of September’s biggest releases for our monthly column

Perhaps it’s the book nerd in me, but I do enjoy a good index. And they seem to be getting rarer. In Dennis Duncan’s Index, A History of the: A Bookish Adventure (Allen Lane) we learn that famous “literary indexers” include Virginia Woolf, Alexander Pope and Vladimir Nabokov. Surprise, surprise, Duncan also tells us that indexers have historically been “overwhelmingly women… for the most part, anonymous, their work uncredited”.

Simone de Beauvoir’s “lost novel”, The Inseparables (Vintage, translated by Lauren Elkin), returns to one of her pet subjects – the story of her inseparable childhood friendship with the tragic Zaza (Andrée in this story). The book, tame to 21st-century eyes, was considered “too intimate” to be published in 1954. The novel also reflects de Beauvoir’s rejection of religion. In one telling moment, her character Sylvie mocks the “blather” of the “gossipy old” priest. “I fled the chapel without doing my penitence. I was more shaken than that day on the metro when a man had spread open his overcoat to reveal something pink.”

Psychiatry professor Joel E Dimsdale’s Dark Persuasion: A History of Brainwashing from Pavlov to Social Media (Yale University Press) is teeming with intriguing tales of mental manipulation, including accounts of the Jim Jones cult, Patty Hearst’s post-kidnap transformation and the whole thorny subject of Stockholm Syndrome.

Professor Bobby Duffy’s Generations: Does When You're Born Shape Who You Are? (Atlantic Books) is an insightful read for those interested in understanding changing social attitudes and behaviour, and most importantly he helps to bust damaging myths about generational stereotypes.

I lost interest pretty early in Robert Peston’s pedestrian debut political thriller The Whistleblower (Zaffre), whose protagonist is a fearless 1990s Lobby journalist called Gil Peck, a man who prides himself on exposing the “secrets of the powerful, rich and pompous”. One suspects, alas, that Peston really believes himself to be exactly this kind of fearless investigator.

Did I Say That Out Loud: Notes on the Chuff of Life (Trapeze) feels like a podcast repackaged as a book, although authors Jane Garvey and Fi Glover are as amiable on the page as they are on their show. I particularly enjoyed Glover’s guide to things she wished she’d known before leaving home, including her advice that

1) if the chicken smells off, it probably is;

2) if he smells off, he probably is;

3) If you smell off, go and see a doctor.

Garvey, who was born in Liverpool and was a teenager there during the 1981 riots, admits “to my shame, I honestly had no real idea where Toxteth was, nor what its problems were”. Someone who could tell her all about it is Malik Al Nasir (formerly Mark T Watson), who once gave Gil Scott-Heron a tour of the burnt-out buildings in the district after the violence. In Letters to Gil: A Memoir (William Collins), Nasir tells the story of his life – including his brutal treatment in care homes as a child – and his friendship with the musician-poet. His candid, eye-opening story includes a joyously uplifting tale of the time he accompanied Scott-Heron to meet Stevie Wonder.

Part fiction, part essay, Duncan White’s A Certain Slant of Light (Holland House Books) was shortlisted for the Fitzcarraldo Prize. It’s a beguiling, graceful meditation on absence and grief. As an original Holborn boy, I couldn’t help agreeing with poet Tom Chivers when he described St Etheldreda’s church as “part of a sacred landscape”; that description is one of a plethora of delights in London Clay: Journeys in the Deep City (Doubleday), his highly original guide to our capital city.

My thriller of the month is The Man on Hackpen Hill by JS Monroe (Head of Zeus), an impressive twisty tale, set in Wiltshire, in which Detective Silas Hart has to discover the truth about a dead body in a crop circle. Finally, Colm Tóibín’s The Magician (Viking) is a complex, absorbing fictional biography of Death in Venice author Thomas Mann, whose life overflowed with tragedy.

Tennis legend Billie Jean King’s memoir, along with novels by Sally Rooney, Joshua Ferris, Sebastian Faulks, Gayl Jones and Richard Powers are reviewed in full below.

Snow Country by Sebastian Faulks ★★★★★

Snow Country opens with a dramatic three-page scene, set in a military field hospital, as a surgeon, using a blunt scalpel and able to work only by the dim light of two kerosene lamps, battles to remove shrapnel from a soldier listed as “A Heideck”. This “poor soul” survives, left with mental scars as permanent as the one disfiguring his back.

The second book in Sebastian Faulks’s planned Austrian trilogy – which like the first, Human Traces, can be read on its own, without reference to the other – again deals with the workings of our conscious minds, but is more about the resilience of the human spirit.

Faulks, whose 14 previous novels include the war classic Birdsong, examines the consequences for lives that have been through the horror of conflict, and how it’s hard for a man such as Anton Heideck to prevent that terrible experience flooding him with its blood and poison “into thinking all life before and after was meaningless and absurd”.

Snow Country, whose title is taken from Nobel Prize winner Yasunari Kawabata’s celebrated 1956 novel, is set in three time periods: 1914, 1927 and 1933. In the first section, as Europe teeters on the brink of war, Anton is making his name as a journalist and Faulks provides rich entertainment in detailing his escapades, especially when his young Austrian protagonist is reporting on the construction of the Panama Canal. Faulks was, of course, a journalist himself – indeed, he was the first literary editor of The Independent back in 1986 – and his depiction of a jaded, jaundiced correspondent called Maxwell is particularly enjoyable.

Historical events and people – including the notorious killer Henriette Caillaux – are part of the crevasses Faulks explores in Snow Country, but the heart of the book is about the two love stories that dominate Anton’s life: his doomed affair with an older woman called Delphine and his possibly doomed love for Lena, a girl born to an alcoholic mother in a small town in southern Austria in 1906. For the innately compassionate Lena, life has been “little more than a battle with need: keeping herself alive while relying on the whim of others”.

In the key final section, when middle-aged Anton is sent on a commission to write about the mysterious Schloss Seeblick clinic (where Faulks hands a small walk-on part for Human Traces psychologist Jacques Rebière), the former soldier acknowledges that his emotions are blocked “like a Panamanian mudslide”. It is in that frozen Austrian retreat, home to a host of quirky, stimulating characters, that he encounters Lena again. For this troubled woman Schloss Seeblick is “not just a new place but a new world”.

To say any more would spoil the story. It’s enough to recommend this magnificent, moving novel, part of the joy of which for the reader is joining Anton and Lena on their intensely affecting journey to find a way to live with their tortured pasts. Although the book is full of sorrow, it also shows us how the power to love somebody for what they are – and all that they are – can bring solace during our short time “on this woebegotten earth”.

Snow Country by Sebastian Faulks is published by Hutchinson Heinemann on 2 September, £20

Beautiful World, Where Are You by Sally Rooney ★★★☆☆

Sally Rooney’s acclaimed 2018 novel Normal People sold more than a million copies, and the BBC adaptation was an Emmy-nominated triumph. The television version of her debut novel Conversations with Friends is in production. It’s no surprise that her third novel, Beautiful World, Where Are You, comes with a huge buzz.

Alice Kelleher, one of the main characters, is a 29-year-old wunderkind novelist who has moved to a coastal town in Ireland after a breakdown in New York. Her status as celebrity author is part of why she describes her life as “difficult”, and the psychological price of success is a theme of Rooney’s novel. There are three protagonists besides Alice: Felix, her lover; Eileen, her oldest friend; and Simon, a parliamentary adviser.

Rooney writes sharply and discerningly about her fellow millennials. The conversations about the rental market, Netflix, internet porn, ghosting, sexual fluidity and “worst break-ups” will surely strike a chord with those youngsters who think and talk like her characters.

Its third-person occasional narrator jokes about how gushing reviews of Alice’s first two books were followed by “negative pieces reacting to the fawning positivity of the initial coverage”. There’s no disarming pre-emptive strike needed here, though, because overall Beautiful World, Where Are You is a stimulating, enjoyable read. My main problem was that aside from rooting for the insecure, hyper-sensitive Eileen, I could not find it in my heart to care in the least about Alice, taciturn Felix or whiny Simon.

Beautiful World, Where Are You by Sally Rooney is published by Faber on 7 September, £16.99

Click here for a full separate review of the book.

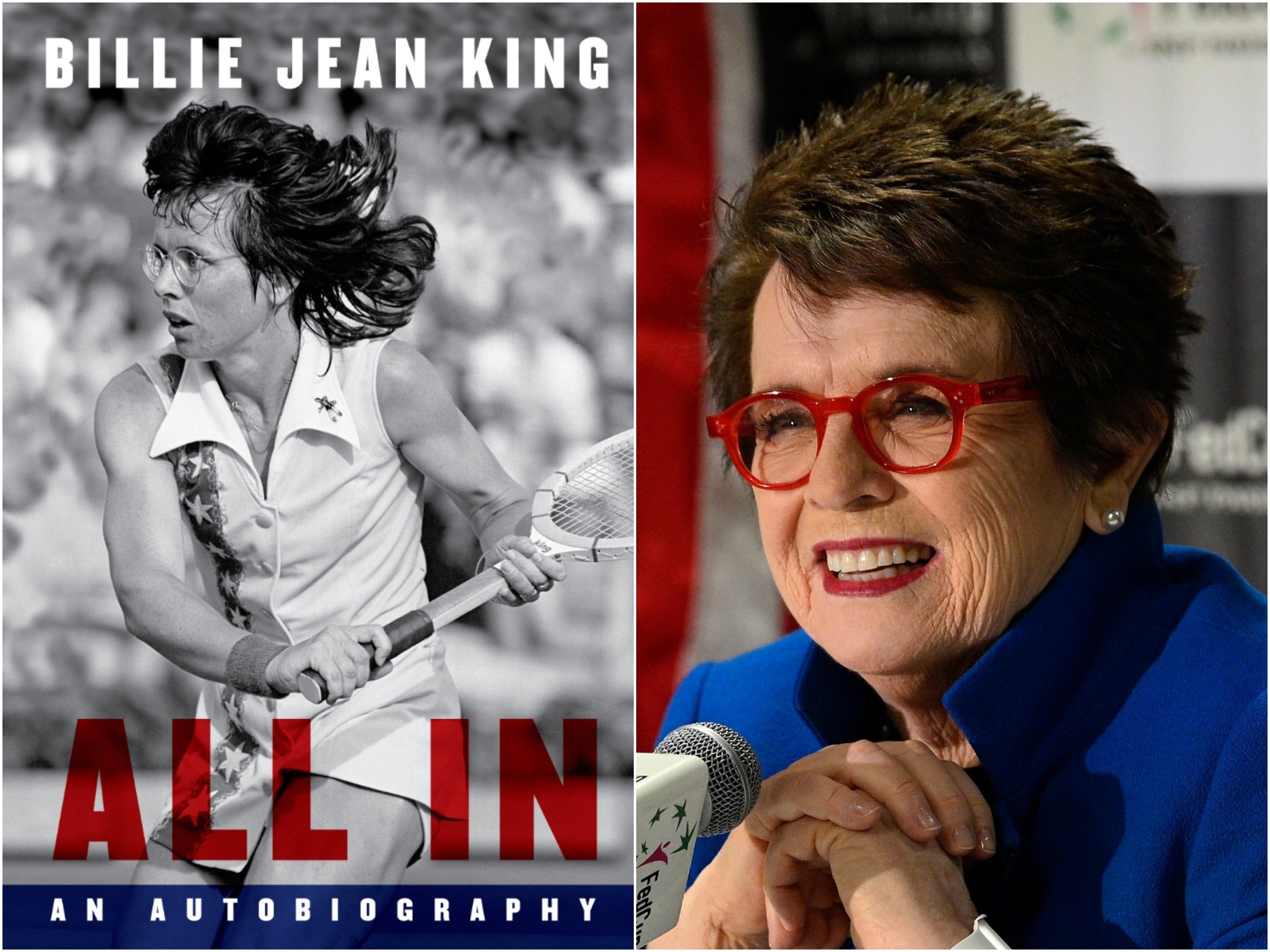

All In: The Autobiography by Billie Jean King ★★★★★

Billie Jean King won 39 Grand Slam titles (12 of them singles, six of which came at Wimbledon) and was a true pioneer in fighting sexism in sport. The 77-year-old’s wonderfully candid memoir All In tells the story of a remarkable career on and off the court.

Even as a youngster, King was battling the sexism of the 1950s tennis world. One of her “friendly” advisers told her, “You’ll be good because you’re ugly”, and Perry T Jones, the dinosaur who was president of the Southern California Tennis Association, presented her with a doll when she won a tournament as a teenager. “A baby doll. Seriously?” says King, in recollections laced with humour. Even after becoming the youngest ever female Wimbledon doubles champion, King had to work menial jobs to fund her career.

In her autobiography, King lifts the lid for the first time on her own #MeToo moment. Aged 16, she had to fight off a married man who tried to sexually assault her during a trip back from a tournament. “I punched him so hard in the chest it stunned him,” she recalls.

King, well served by thorough ghostwriters Johnette Howard and Maryanne Vollers, offers an intriguing account of her family history and also writes openly about her eating disorders, weight problems, her failed marriage to Larry King, her abortion and her own tortured sexual awakening and the difficulties she faced in admitting her attraction to women.

King was finally publicly “outed” in 1981, after an unstable former lover called Marilyn Barnett went to the press. The reaction to the news offers a sharp reminder of how backwards attitudes were in those days. King was dumped by numerous sponsors; and the chief executive of Charleston Hosiery even called her a “slut”, in a letter announcing she had been fired as their public face. Even for someone used to being in the limelight, King conveys with real feeling how tough it is to have your private life become a matter of public debate.

Although King’s inspirational activism is a key element in the book, what really makes All In such a magnificent memoir are her insights into being a tennis champion. King goes into great detail about the notorious 1973 “Battle of the Sexes” match with retired men’s champion Bobby Riggs, delivering a riveting account of a ground-breaking contest that changed the public perception of female sports stars. As well as humorously explaining why she was so desperate to beat a “creep” who “runs down women”, she also makes you understand why they became friends in later years.

For anyone (hands up, me included) who has spent their life enjoying playing tennis, King articulates quite beautifully why the game offers such a captivating mental challenge to any inquisitive, highly energetic kid. “I liked being able to hit the ball over and over,” writes King. “I loved the drama of it all… chasing down each ball, the universe of possibilities that opened up as I drew my racket back, then that split-second pause where everything hangs in the balance as you’re preparing to hit a return. There was something swashbuckling and instantly addictive about all of it.”

Her insights into the psychology of other top players are also fascinating, especially about their hatred of losing. Steffi Graf told King that she used to pace the floor for days after she lost; Chrissie Evert “trashed her London hotel room and stayed in her bathrobe for three days eating junk food” after her 1977 Wimbledon semi-final loss to Virginia Wade.

All In is the story of a true champion with an indomitable spirit. I doubt there’ll be a better sports book in 2021.

All In: The Autobiography by Billie Jean King is published by Viking on 9 September, £20

Palmares by Gayl Jones ★★★★☆

Near the start of Palmares, the first published novel in 21 years from Gayl Jones, the protagonist Almeydita is asked by her mentor Father Tollerine: “Do you think you’ll find your spiritual place in the world?”

You suspect that this is a question 71-year-old Jones has asked herself often during a tumultuous, tragic life. Jones, born into poverty in Lexington, Kentucky’s black district Speigle Heights, made her breakthrough in the 1970s after graduating from Brown University’s graduate writing programme. She was signed to a book contract by Toni Morrison, and her debut 1975 novel Corregidora was praised by John Updike, James Baldwin and Maya Angelou.

Disaster struck in February 1998 when a Swat team raided her Lexington home, to serve a 15-year-old warrant on her husband Bob Higgins. In the subsequent stand-off, Higgins took his own life. Jones was committed to the state mental hospital for the next fortnight. It was a dreadful irony that a full-page glowing article about Jones and her new novel, The Healing, in Newsweek was what led the police to discover Higgins’s fugitive status. Her 1999 novel Mosquito, which had already been in production, was the last fiction seen from Jones until Palmares.

Jones began writing Palmares, which was originally started in verse, in 1980. It is a story about two enslaved lovers who escape to northeastern Brazil. In 2019, having completed Palmares, Jones decided to self-publish the novel in six volumes, before the rights were bought by Beacon Press.

Set in the late 17th century, Palmares is a sprawling, ambitious tale of racial struggle, Portuguese colonial rule, magical realism and mythology, full of imaginative plotlines and language as pungent and varied as the food in the book: everything from rolls with jelly mango and coconut, to onion soup made with wild honey. The book, which opens on a Brazilian plantation, is set in a “country of enchantment”.

The language is colourful (Almeydita’s grandma tells her to shut her mouth before she “swallows a goat”) and the novel is full of quirky historical details, including how Almeydita learns to make a secret poisonous potion from “squeezing the fragrant testicles of a certain lizard”.

Jones evokes a world that is perilous for black enslaved women, in a time and place when sexual atrocities, “all aimed at the groin or the bosom”, were commonplace. Through the eyes of one unusual character, a London society woman called Miss Pepperell, we gain an outsider’s view of the barbarism of the men. As a child, Almeydita is saved by her mother from being assaulted by a man who believes the blood of a black virgin is the cure for his illness. “There’s been a gentleman visitor here rotten with venereal disease who wants one of the little slave girls. Disgusting. He has got none so far and is off to another plantation,” Miss Pepperell reports in her diary.

Over the next 500 pages, we see Almeydita, “stubborn as a donkey”, grow to adulthood and embark on a heroine’s quest to find a hidden settlement for fugitive slaves, and re-join her husband. This epic quest, told in hundreds of short, spiky chapters with eye-catching titles, is full of natural hazards and human predators.

Palmares is certainly an acquired taste, but it’s good to have a new novel from Jones, especially one which is a sublime feat of imagination.

Palmares by Gayl Jones is published by Virago on 14 September, £18.99

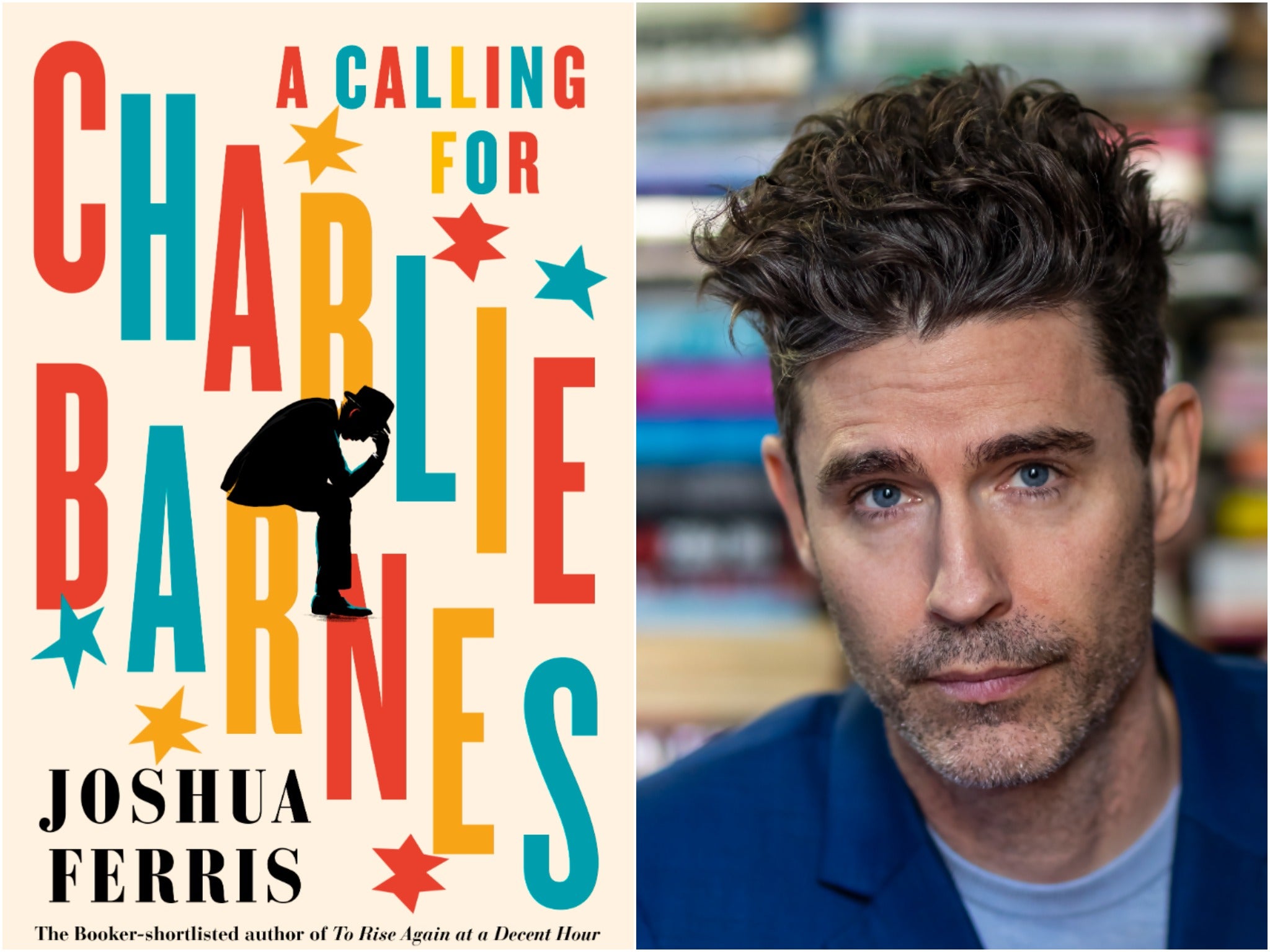

A Calling for Charlie Barnes by Joshua Ferris ★★★★☆

We all allow ourselves, to varying degrees, to live a lie. Few of us are called out on our dishonesty as sharply as Charlie Barnes, the central character of Joshua Ferris’s splendid new novel A Calling for Charlie Barnes, with even his closest family members variously dubbing him a “fraud”, “deadbeat”, “phony” and “con man”.

Could you believe this rascal if he told you he had pancreatic cancer? That’s the dilemma for his family, including Jake Barnes, the fourth wall-breaking narrator of the novel. Barnes, whose name is presumably a nod to Hemingway’s narrator in The Sun Also Rises, is writing his foster father’s life story. When he confronts Charlie about the grey areas in his past, he is told, “historically, Jake, no one in my family has been very good at telling the truth”.

The slippery, dubious nature of the relationship between life and the written word is one of the themes of a novel that Ferris first began planning after the death of his own father in 2014. Ferris has his cake and eats it, of course, allowing Jake to admit, “I’m not the only one who still makes s*** up. I just happen to get paid for it. I’ve professionalised the family curse!”

Another theme of the novel, which is mainly set in 2008, is America’s financial dishonesty. Charlie, who is trying to recover from disastrous losses caused by the plummeting stock market, rails against a country that has become “entirely f***ing corrupt”. The American Dream, he says, is nothing but a scam, a place where “an honest man was a damn dog in this world, made to heel and told to stay put, while the dishonest man got filthy stinking rich and stuck the country with the tab”. The book nails our own false age, where everything is about the projection of a successful image.

Ferris, who burst on to the literary scene in 2007 with his debut novel Then We Came To An End, a truly witty satirical depiction of office life, admits that he comes from “a very illustrious line of divorcees” (his mother and father were wed four times each), and multiple marriages is another theme of this thoughtful, intimate novel.

There are lots of amusing remarks – the 1970s is described as an era when “men in America dressed up like cubist paintings”; one misshapen great-aunt is “all bird above, brontosaurus below” – and lots of alliteration amid a memorably affectionate, biting portrait of an old family patriarch, described as “Updikean in his defects and indulgences”. Ferris recognises the bittersweet truth that we miss even those loved ones who drive us mad.

No giveaways but the final 50 or so pages, in which Charlie’s family confront Jake over the content of the tell-all memoir, is easily the funniest chapter of a novel I’ve read all year.

A Calling for Charlie Barnes by Joshua Ferris is published by Viking on 16 September, £16.99

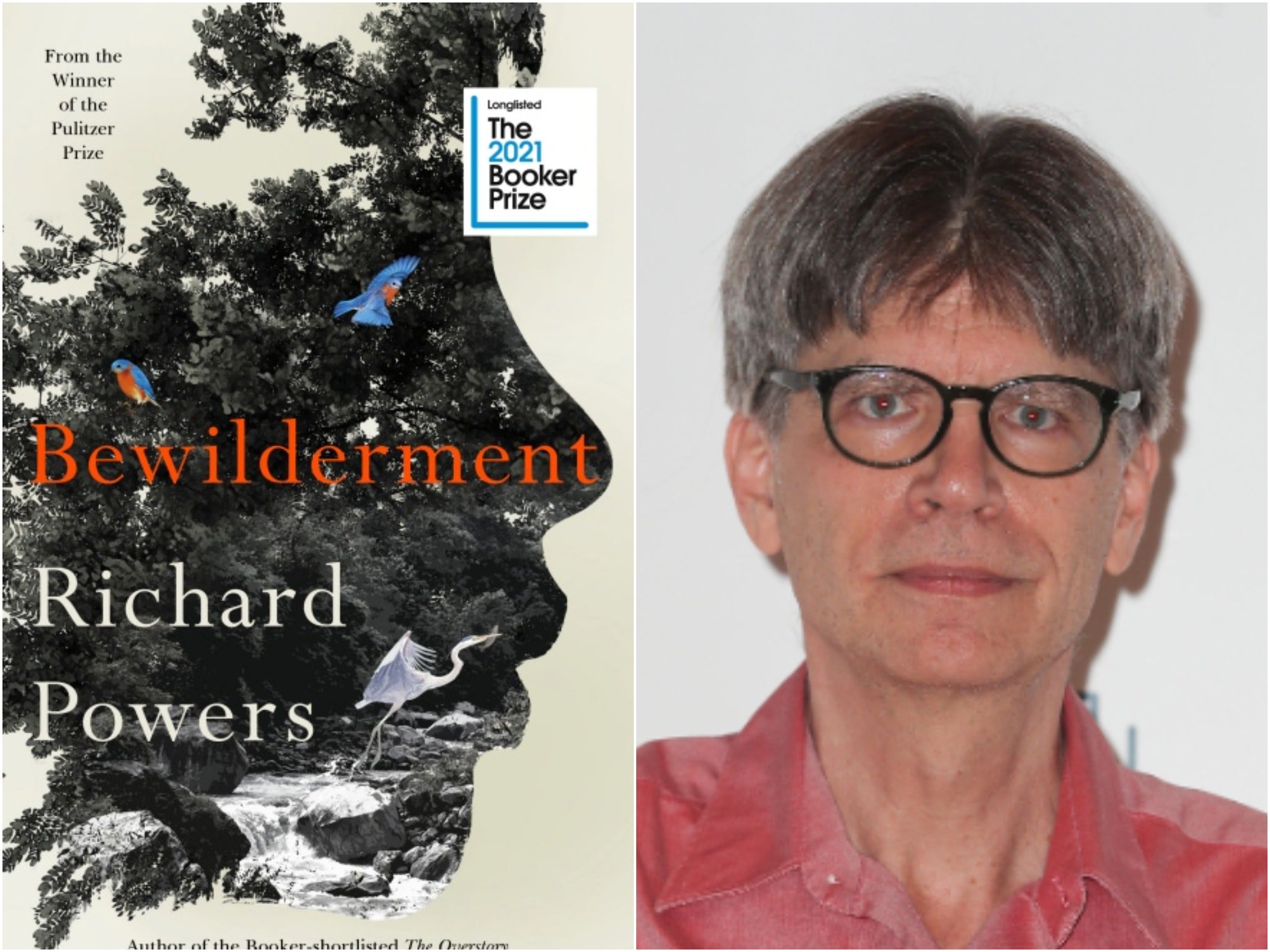

Bewilderment by Richard Powers ★★★★☆

“Life became a fire drill from the moment Robin came out of the incubator,” says widowed astrobiologist Theo Byrne, the narrator of 2021 Booker Prize-longlisted Bewilderment, about his troubled nine-year-old son.

The power of this outstanding novel comes from the description of a fraught father-son relationship, which is lived in the shadow of Robin’s late mother, Alyssa, a woman who died fearing that “the world is going to take this child apart”.

At the start of the novel, Theo takes his son, in trouble for attacking a classmate at school, on a camping trip. Powers, author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel The Overstory, lives in the Great Smoky Mountains, and his descriptions of the natural wonders of the Southern Appalachian mountains, a place where there are more tree species than in all of Europe, are stupendous.

Bewilderment offers a heartrending account of a father’s anxious battle to help his on-the-spectrum child overcome grief and rage without resorting to psychoactive drugs. They try out an unusual form of neurological therapy – the book references the science fiction classic Flowers for Algernon – and find comfort in imagining other planets and what goes on in distant galaxies.

Powers shows us the marvels of existence through the eyes of a confused, frightened and angry child. Theo wonders how any of us can survive “this Ponzi scheme of a planet”, one where the human race is mutilating nature at every step. Bewilderment is very much of our times, with political leaders who “test the outermost limits of public gullibility” and revel in their hostility to scientific research.

Poor Theo admits to “doom-scrolling” on the internet and although there is an element of that in this gimlet-eyed look at modern America, the novel is also an enriching planetary romance. Robin is a memorable, heart-wrenching character and Bewilderment is a bleak, stirring work.

Bewilderment by Richard Powers is published by Hutchinson Heinemann on 21 September, £20

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks