Books of the month: From Hilary Mantel’s ‘The Mirror & the Light’ to Maggie O’Farrell’s ‘Hamnet’

Martin Chilton reviews six of March’s releases for our monthly book column

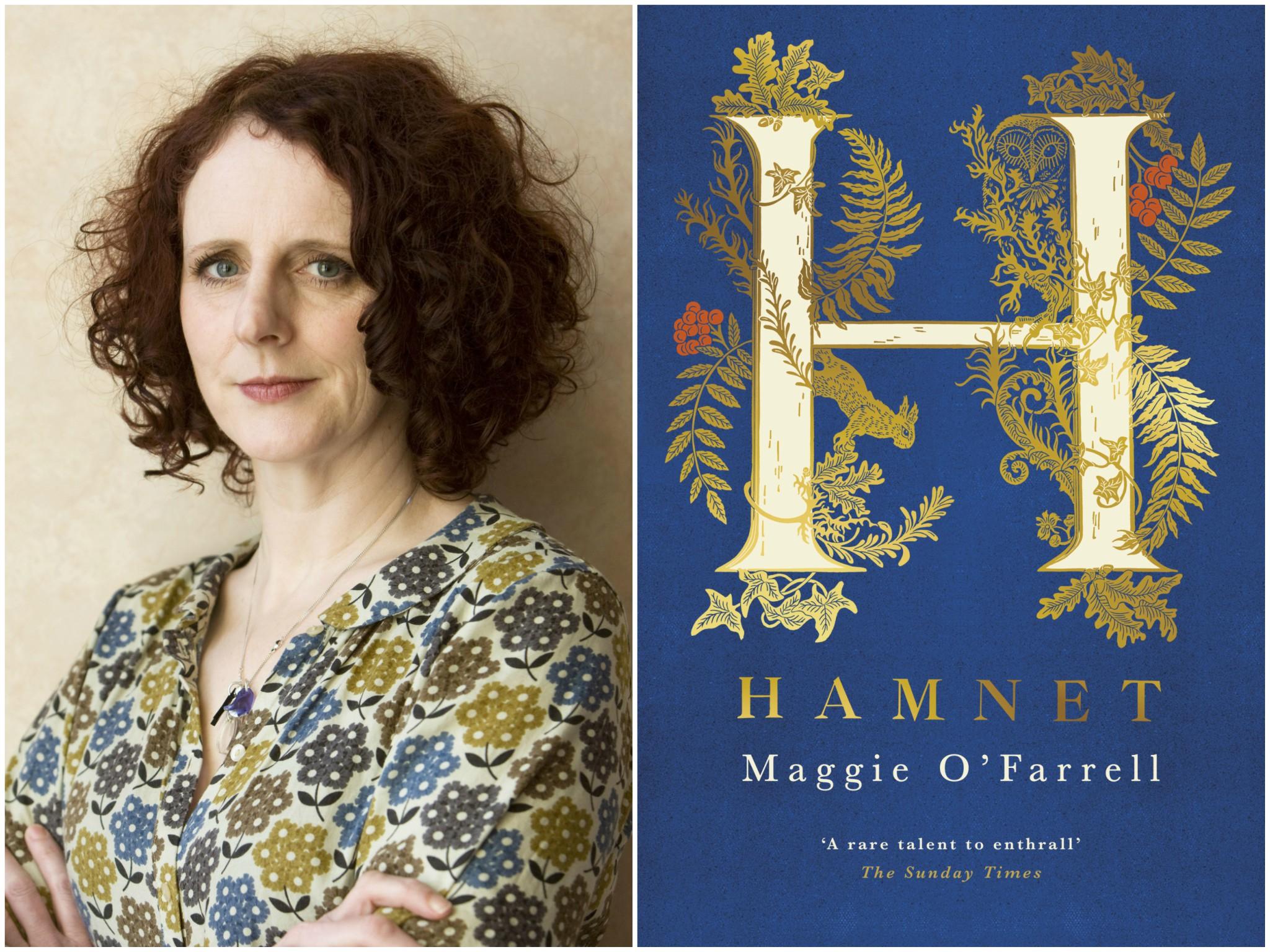

Thomas Cromwell and William Shakespeare are brought brilliantly to life in new novels by Hilary Mantel (The Mirror & the Light) and Maggie O’Farrell (Hamnet). The novelists, both giants of modern literature, are astute chroniclers of the human experience, and their respective works of historical fiction are rich with the sights, smells and textures of 16th-century England. As you would expect, they are also full of penetrating insights into two remarkable characters.

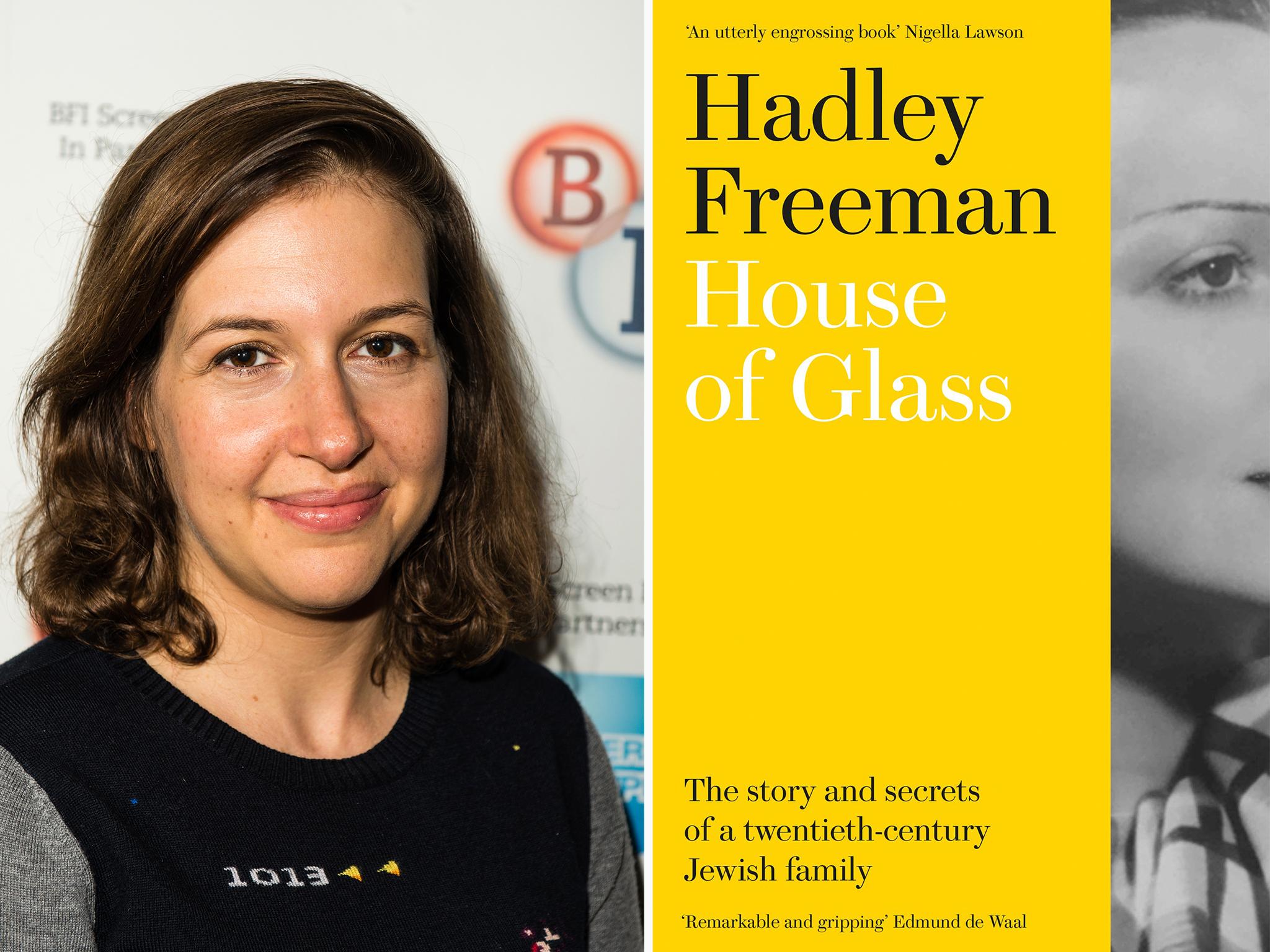

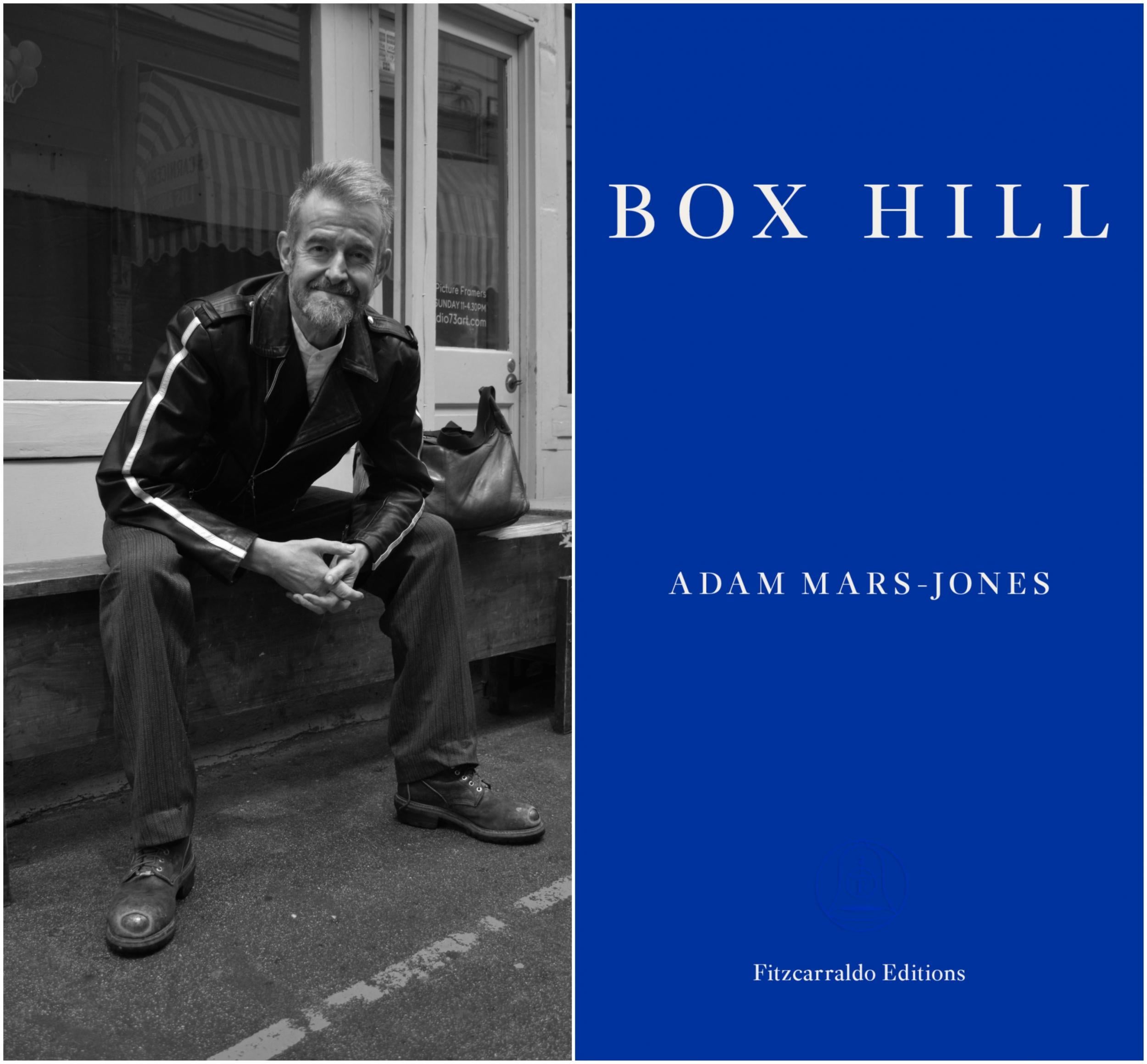

March is also a boom month for memoirs set in the 1970s. Stuart Maconie’s The Nanny State Made Me is part-witty memoir and part-stirring defence of the benefits of the welfare state; while Pete Paphides’s Broken Greek is an amusing tale of growing up and being influenced by music, football and television. House of Glass by Hadley Freeman is an achingly poignant history of her Jewish family and the traumas it faced in the 20th century. All five books mentioned so far, along with Adam Mars-Jones’s novella Box Hill, are reviewed in full below.

Paphides was an elective mute as a young child, as was Greta Thunberg. Our House is on Fire: Scenes from a Family and Planet in Crisis (Allen Lane) by Malena and Beata Ernman, and Svante and Thunberg tells the family story of the teenage climate activist. Thunberg was taken to the Centre for Eating Disorders in Sweden and diagnosed with high-functioning autism. “We could formally diagnose her with selective mutism, too, but that often goes away on its own with time,” her mother was told. Happily, she found a voice – and it’s one our crumbling world needs to hear.

The phenomenon of celebrity – a term first used in 1849 to describe stardom – is explored in Dead Famous: An Unexpected History of Celebrity from Bronze Age to Silver Screen (Weidenfeld & Nicholson). Greg Jenner, the consultant to Horrible Histories, looks at the poets, actors, writers, singers and criminals who have come under fame’s freakish spell. The PBS show An American Family (1971-1973), which is considered the first television reality series, turned Lance Loud into that genre’s first celebrity. “Lance who?”, do you say? He died in 2001, at 50, and his final words included an expression of regret over the harmful effect the show had on his family. Jenner describes celebrity as “a form of harmless radioactivity”, although the danger to the mental health of those in the public eye is increasingly obvious.

Loud’s notoriety came a few years after Andy Warhol’s 1968 prophesy that “in the future, everyone will be world-famous for 15 minutes”. Warhol’s fame has endured, however, and he is the subject of an impressively detailed 900-page biography by Blake Gopnik. Warhol: A Life as Art (Allen Lane), coincides with the Tate Modern opening a six-month exhibition of the artist’s work.

Warhol, who died in 1987, may well have been an Instagram influencer in today’s world. Professor Matthew Cobb’s authoritative The Idea of the Brain: A History (Profile Books) includes a withering assessment of the supposedly enslaving nature of feelgood neurotransmission on social-media users. “There is no evidence that Twitter has hacked your dopamine system,” writes Cobb. “The claim that all addictive behaviour can be blamed on dopamine is an example of what is commonly called neurobollocks.”

A recurring pattern in some of the best books this month is the predatory nature of some men and the suffering of women. Rebecca Solnit’s essay Men Explain Things to Me inspired the term “mansplaining” and her memoir, Recollections of My Non-Existence, is a challenging look at her own feminism. “People watching is one of life’s great pleasures,” says Solnit. Coming into contact with people is not always so enjoyable. The American author gives examples of the horrid harassment she has faced, including the time a stranger spat full in her face.

Evie Wyld’s The Bass Rock (Jonathan Cape) is a powerful tale about the violence men have inflicted on women across the centuries. The novel spans the lives of an 18th-century girl accused of being a witch, a post-war housewife and a young woman facing 21st-century problems. Although The Bass Rock is unsettling, it is humorous and full of sharply observed vignettes, such as the moment when protagonist Viv scales a garden wall in the East Lothian wilds to get a mobile phone signal, only to encounter a small slice of modern misogyny. She gives a friendly wave to three golfers. “None of them wave back. It’s not part of the game, waving at women,” Wyld notes, laconically.

Tayari Jones, the author of An American Marriage, excels again in Silver Sparrow (Oneworld), which is also set in Atlanta in the 1980s. The novel is about two teenage girls caught up in the deceptions of their bigamist father. They find that truth is “a coin that can be pulled from behind your ear”. James Scudamore’s accomplished novel English Monsters (Jonathan Cape) is about the horrors of the boarding school system, while Alain Mabanckou’s The Death of Comrade President (Serpent’s Tail, translated by Helen Stevenson) is an imposing tale of colonialism in the turbulent Congo of the 1970s. Nazanine Hozar’s Aria (Viking) is the skilfully told story of a young woman struggling to find her place in intolerant, revolutionary Iran.

It is another month of cracking debut novels. Kate Elizabeth Russell’s My Dark Vanessa (4th Estate) is a compelling MeToo-era examination of manipulation and the guilt and self-doubt that predatory behaviour implants in girls who have been groomed. “I’m going to ruin you,” declares 42-year-old English teacher Jacob Strane to 15-year-old schoolgirl Vanessa Wye. Adunni, the protagonist in Abi Daré’s The Girl with The Louding Voice (Sceptre), is just 14 when she is sold as a domestic servant and bride to Morofu, a Nigerian who is “king in this house”. Daré’s description of the girl’s miserable, unwilling sexual initiation is desperately sad, and her book gives an eloquent voice to the victims of modern slavery.

Contemporary womanhood is also explored in The Voice in My Ear (Jonathan Cape), the first work of fiction from award-winning poet Frances Leviston. The short stories are crisp and thought-provoking, particularly The Man in Room Six, the tale of a creepy middle-aged hotel guest (“hairs poking from his nose”) and the uneasy young girl who has to bring him room service.

Eliese Colette Goldbach’s Rust (Quercus) is another debut that explores the exploitation of women. The author, a former steelworker who was a rape survivor, has written a gritty coming-of-age memoir. She recalls confronting her own Republican-supporting father about his support of Donald Trump, explaining why she took exception to the president’s boast about “grabbing women by the pussy”. This was “just locker room talk”, her father replies.

Louise Hare’s debut This Lovely City (HarperCollins) tenderly evokes the experiences of the Windrush generation in post-war London, while Jane Healey’s The Animals at Lockwood Manor (Mantle) is a Gothic love story, set in a natural history museum. Healey’s book is another in 2020 to feature startlingly good cover illustrations. Neil Lang based his design on letters used by the Rare Bird Font Foundry and drawings of birds from a 19th-century book of illustrations.

There are plenty of suspenseful tales about missing people in this month’s crop of books. The main character in Sarah Elaine Smith’s Marilou Is Everywhere (Hamish Hamilton) is a teenager on the margins of society, while Kate Bradley’s gripping To Keep You Safe (Zaffre) is about a teacher who intervenes to stop an abduction. Norwegian author Camilla Bruce’s clever Gothic thriller You Let Me In (Bantam Press) is laced with horror and perplexing clues. Dominic Nolan’s After Dark (Headline), based around the story of a girl who has been held captive all her life, is also full of good twists. A more unusual tale of abduction is A Godawful Small Affair (Cherry Red Records) by JB Morrison, the pen name of Jim Bob, the former lead singer of indie band Carter The Unstoppable Sex Machine. When 15-year-old Zoe goes missing, her 10-year-old brother suspects that aliens are involved.

It’s hard to get away from Trump. He even pops up in Stephen Moss’s brilliant nature book The Accidental Countryside: Hidden Havens for Britain’s Wildlife (Faber). Former Springwatch presenter Moss says Trump built his golf course in Scotland on a Site of Special Scientific Interest, destroying one of the most exceptional sand dune systems in Britain in the process.

Trump’s mention is a small sour note in an otherwise thoroughly uplifting book. Among the fascinating ground covered by Moss is the story of the revival of Britain’s peregrine falcon population. If you are in London, Derby, Norwich or Exeter, look up in the sky sometime, and you may well see a pair of the fastest creatures on the planet.

The book also covers the beauty of urban parkland walks, and pays tribute to the progressive policies for countryside verges that are producing mini-nature reserves. Moss also salutes the ecological transformation of former colliery sites – which have allowed different species of invertebrates to flourish in the UK – and enthusiastically explains the joys of London’s Woodberry Wetlands.

Julian Barnes is among the notable writers (a list that includes Jenny Uglow and Simon Armitage) who have contributed to Lives of Houses (Princeton University Press, edited by Hermione Lee and Kate Kennedy), a series of interesting essays about the houses of famous writers, composers and politicians. Barnes’s essay is about the home of Jean Sibelius, and he recalls the words the Finnish composer used to console a young colleague after a bad review. “Always remember, there is no city in the world which has erected a statue to a critic,” said Sibelius.

With that caveat in mind, here are my extended reviews of six books published in March 2020.

The Mirror & the Light by Hilary Mantel ★★★★★

From the razor-sharp opening paragraph to the dramatic ending 863 pages later, Hilary Mantel’s The Mirror & The Light is superb, right to the last crimson drop.

The portrait of Thomas Cromwell that started with Wolf Hall (2009) and continued with Bring Up the Bodies (2012) – both Booker Prize-winning novels – concludes with another masterpiece of historical fiction. The Mirror & The Light opens with the execution of Anne Boleyn in May 1536. She was killed by a hired Frenchman, who used a sword made of Toledo steel from Spain. It’s doubtful the so-called Calais executioner, the foreigner brought in to separate the Queen’s skull from her neck, would have ranked highly on Priti Patel’s points-based immigration system. “A head is heavier than you might expect,” the executioner notes drolly, as one of Anne’s attendants swaddles the severed remains in linen to carry away for burial.

Cromwell is in his early fifties by the time of Anne’s death. As Lord Privy Seal, deputy head of the church in England and chief minister, he is left to organise a new Queen and maintain English power in Europe, while outmanoeuvring enemies close at home. Cromwell, we are told, is always there to “shovel up the shit”.

Mantel’s depiction of royal court intrigue is excellent. She captures the atmosphere of a place choking on itself, where councillors take turns at being humiliated. Cromwell, a former cloth merchant, a self-made man, is at the centre of most machinations. He is constantly watchful. He posts guards at every door. “The times being what they are, a man may enter the gate as your friend and change sides while he crosses the courtyard,” he remarks. Everything is a performance for this scheming, hateful man with “small, quick eyes” and “a black heart”.

Mantel’s Cromwell trilogy, set in such an accessible period for historical fiction, has deservedly struck a real chord with the reading public – and this concluding instalment has understated messages for our own era of conflict and unbridled ambition. The Mirror & the Light takes place from 1536 to 1540, a time of rebellion, when “England is collapsing in on itself, like a house of straw”. Henry worries that Europe regards England as a “low-hanging fruit, exhausted game”.

Mantel depicts a king capable of turning on those closest to him at any moment. When Henry is sporting a turban (he liked dressing up in Turkish costumes), Cromwell kneels at his feet but does not praise the outfit. “There is a limit to how much awe a man can feign,” Mantel notes. Even a master of dissimulation such as Cromwell can run out of luck, but maybe he always knew his end would be bleak. “This is what life does for you in the end; it arranges a fight you can’t win,” he says, sitting in jail like a piece of “broken meat”.

The Mirror & the Light is another shrewd character portrait of Cromwell, and it is also a complex, insightful exploration of power, sex, loyalty, friendship, religion, class and statecraft. A single reading hardly seems sufficient to grasp the intricate treasures of Mantel’s novel – but it is enough to know for sure that The Mirror & the Light is a stunning conclusion to one of the great trilogies of our times.

The Mirror & the Light by Hilary Mantel is published by 4th Estate on 5 March, £25

Broken Greek by Pete Paphides ★★★★★

The 1970s was a weird era. Nine-year-old Jimmy Osmond was at No 1 for five weeks in December 1972, singing a pop hit called “Long Haired Lover from Liverpool” in which he promised to “do anything you ask”. In Broken Greek, Pete Paphides’s memoir of growing up in the suburbs of Birmingham in that decade, the young Mormon singer is described as the “twinkle-eyed Satan of kid-pop”. It’s one of many fine lines in a book that will leave you smiling.

Although lots of the references – Rod Hull and Emu, the Wombles, Evel Knievel, Findus Crispy Pancakes (yuk!) and the comics Whizzer and Chips and Whoopee! – will obviously resonate more with old farts like me than millennials, readers of all ages will find much to enjoy in a humorous portrait of a bygone age. The book is also a loving testimony to the part music played in helping Paphides find a cultural identity. The music journalist and DJ writes passionately about the role that bands – ABBA, the Police and Madness, in his case – play in one’s formative years.

There is also plenty in the book for football fans. His quips about the players who featured on Panini stickers in the 1970s are pitch-perfect. For example, England’s once-capped lugubrious-looking goalkeeper Phil Parkes is nicely nailed by Paphides, who says the player bore “the faithful grin of a beloved Afghan hound”.

Broken Greek is also a highly personal book about family life and the problems the young Paphides saw in his mother and father’s relationship. Nevertheless, he offers a warm-hearted observation about coming to terms with a difficult family past. “It doesn’t feel useful or fair to stand in judgement,” he writes. “What feels more useful is to accept that things happen and that you can try to understand them in the hope that the mistakes of the past aren’t repeated.”

Broken Greek by Pete Paphides is published by Quercus on 5 March, £20

The Nanny State Made Me: A Story of Britain and How to Save It by Stuart Maconie ★★★★☆

Stuart Maconie also has a real gift for bringing to life the bizarreness of the 1970s. His description of bus rides is terrific, recalling the dangerous thrill of climbing the stairs to the upper level, where smoking was practically compulsory. “The top deck was really a kind of filthy, penumbral speakeasy, dangerous and secret, the air blue with Player’s smoke and obscenities which stung your eyes and throat and made your hair and school blazer reek”, he writes in The Nanny State Made Me.

The 58-year-old writer and presenter tells his own life story with wit. He was raised in a working-class home in Wigan and attended a Catholic grammar school run by the Christian Brothers “who seemed about as Christian as Pol Pot”. The book details excursions around Britain, including a self-mocking return to his northern hometown. “I became very aware of my man-bag,” he jokes.

The Nanny State Made Me will reverberate with anyone who grew up swimming in council-run pools that reeked of chlorine; re-enacted FA Cup classics in kick-arounds at public parks; or simply wondered about “the curious cross-species ménage à trois that was Hector’s House”. If, like me, you’ve also had your tonsils out, fumed at Wimbledon wannabees invading your council tennis courts for two weeks each summer, and undergone the strange rite-of-passage involving collecting “supplementary benefits” from “the dole”, you will start to feel eerily companionable to Maconie.

Although he is clearly describing a lost world – one where tattoos were the preserve of the aging Teddy Boy or the ex-squaddie – it was apparently a happier one. Maconie quotes a study from the University of Surrey that calculated 1976 to be “the best year in modern British history”. It seems so distant from a 21st-century world colonised by Amazon, Google, Apple, Microsoft and Facebook.

The heart of the book, though, is about modern Britain and the calamitous effect of privatisation and outsourcing. Jacob Rees-Mogg – “a kind of alt-right Harry Potter” – and Chris Grayling are recurring targets. The former transport secretary even gets his own adverb (“most Graylingly of all”) in reference to the £50m of public money he wasted during the Brexit debacle on a contract to a ferry company with no ships.

Maconie offers a strongly argued counterpoint to the “false and damaging narrative” about the so-called “nanny state” of the 1970s. “What was so terrible about properly funded hospitals, student grants, decent working conditions, affordable houses, trains that ran for convenience not profit, water that poured from the tap whose function was to slake your thirst, not to make shareholders a dividend?” he insists. “What exactly was so wicked about public libraries, free eye tests and council houses? We may be coming to realise that the people who complain about the nanny state are the people who had nannies.”

This book will obviously appeal to old snowflakes (hands up, me included) who believe that there is a necessary thing called society and agree with Maconie’s assessment that “a man or woman who would close a library is capable of anything”.

The Nanny State Made Me: A Story of Britain and How to Save It by Stuart Maconie is published by Ebury Press on 5 March, £20

House of Glass by Hadley Freeman ★★★★☆

The family tree at the start of House of Glass comes in useful as you track Hadley Freeman’s story of her Jewish family and the horrors they faced. One of the most endearing characters is Alex Glass, who had an extraordinary escape when he jumped off a train on the way to the death camps and hid in a pile of manure to escape the Nazi soldiers hunting him. He went on to became a wealthy art collector, and a friend of Pablo Picasso. “Life is worth the trouble of fighting death,” was the last line of his memoir.

The early sections of House of Glass are mentally bruising to read, especially Freeman’s account of what the Glahs family (they anglicised their surname) faced in Poland in November 1918, six days before the end of the first world war. Antisemitics in Chrzanow attacked Jews “like wild beasts”. Among the witnesses was Freeman’s grandmother Sala (Sara), then just eight years old, and her 17-year-old brother, Jehuda. They knew some of the attackers. “Something in me died in the face of this inhuman explosion of savagery. From that day, my childhood was over,” Jehuda recalled.

The violence of 1918 was a mere dress rehearsal for the second world war, when 90 per cent of Poland’s Jews were murdered, many “denounced, hunted and killed by the Poles themselves”. Forty Jews were slaughtered in Kielce on 4 July 1946, a full year after the end of the war.

Sara escaped France just as Hitler rose to power. The Glass tendency was “to obsess privately about the past,” explains Guardian writer Freeman. She originally knew precious few details of Sara’s story. Long after her grandmother’s death, Freeman found a shoebox tucked in a closet that contained letters, photographs and documents that provided vital investigative tools for the book. It is possible Sara would not have wanted this tale told, but she was incapacitated by a stroke and died before she could destroy the evidence.

Sara escaped poverty and pogroms when she fled to America, but she did not leave all her troubles behind. She married a man she didn’t know well, or even really like. Life for this elegant French Jew in the rough Long Island town of Farmingdale was tough. Outside the walls of the home there was still antisemitism – the town had a thriving John Birch Society and Ku Klux Klan sect – and inside she was bullied by her husband’s disapproving American family.

“Individual lives are always more complicated than sweeps of history,” says Freeman, who tells the family history with panache. The photographs in this excellent book are evocative, and Freeman, who makes little of her own battles with anorexia, is a balanced family historian, a chronicler who understands the vulnerability of historical truth.

Antisemitic acts are on the rise again throughout the world, and Freeman notes that 41 per cent of Americans “do not know what Auschwitz is”. The poor people gassed to death there included Sara’s cousin, Rose Ornstein. After relocating to America, Sara received a postcard that had been held up in the post for several years. It contained Rosa’s final, heartbreaking message: “They are coming for me. I love you. Goodbye.”

House of Glass by Hadley Freeman is published by 4th Estate on 5 March, £16.99

Box Hill by Adam Mars-Jones ★★★★☆

Box Hill is a beautiful part of the Surrey Hills. The local Rotary Club might prefer to think of it as a place for picnics, Easter Egg hunts and bicycle trips, but in Box Hill, Adam Mars-Jones’s tragic love story set among the gay biker community of the 1970s, it is also where people went for an entirely different sort of pleasure ride.

The author has a sure touch as he conjures up an England from half a century ago. It’s a time of lax concerns over drink-driving, where people waited over a week to get their holiday ‘snaps’ back from the chemist and where local cub scout Akelas were still a big deal. However, there is an underbelly to all this nostalgia, one suggested in a wry reference to buying kaolin and morphine over the counter from the chemist: a medicine that had enough legal drugs to stupefy an adult.

Londoner Colin, the protagonist and narrator of Box Hill, ventures to Surrey one Sunday afternoon for an 18th birthday trip out. He literally trips over a cool biker called Ray. This dramatic outdoor assignation marks the start of a strange six-year relationship, which is explored by Mars-Jones in this subtle, biting novella. Colin, who left school at 15 because he was “short and fat and tired of being bullied”, can’t believe that charismatic Ray would even take a second look at him.

There is a sinister undercurrent to the mysterious Ray. He is controlling and weirdly secretive. It’s hard not to sympathise with Colin, whose role seems to include having to sexually gratify other members of the biker commune. “All for one, and Colin for everybody. Colin on demand,” he notes grimly.

Box Hill is also a profound exploration of parenthood in the 1970s, and reveals the dismal realities of having to keep your sexuality hidden at home, especially from a dried-up father. One of the most telling comments is when Colin reflects that his mum’s final years with her husband “were more like being under house arrest than like being married”.

Although repressed boomers of Surrey are probably not the target audience of this intimate, stirring novel, they would probably enjoy this portrait of an impossibly lost age. Ray and his gang ride famous British motorbikes such as Triumphs, Royal Enfields and Nortons. On the day I finished reading Box Hill, I noticed a newspaper story about Norton Motorcycles, who were founded in 1898, going downhill into administration.

Box Hill by Adam Mars-Jones is published on 18 March by Fitzcarraldo Editions, £10.99

Hamnet by Maggie O’Farrell ★★★★★

In his plays and poetry, Shakespeare almost seemed capable of taming brutal reality, such was his gift for expressing lightly the unbearable. In real life, his only son, Hamnet, twin of Judith, was just 11 when he died, killed when the pestilence sweeping Europe reached Stratford-upon-Avon in August 1596. “No, my love, he will never come again,” says the playwright’s sobbing wife Agnes in the novel (echoing Lear’s “thou’lt come no more” to his dead child Cordelia).

In Hamnet, Maggie O’Farrell tells the agonising story of the boy’s death and the part this family disaster played in inspiring Shakespeare’s famous tragedy Hamlet, written a couple of years later. The England of Shakespeare is so softly and cleverly recreated by O’Farrell that you feel as if you can actually smell the flowers and herbs, touch the fabrics, taste the food and hear the mice in the walls.

At the centre of the story is Shakespeare’s wife Agnes (Anne Hathaway), who was 26 when, pregnant with their first child Susanna, she wed the 18-year-old son of a glove-maker. Agnes is a fascinating character, a woman “of another world”. When she takes hold of the skin and muscle between a person’s thumb and forefinger, with a firm, intimate grasp, she can foretell their future. Sometimes she does this just by looking at a person. After spotting a neighbour with grizzled hair and a yellowish tinge to his face, she knows he is doomed. “He will not last a year, Agnes thinks, the fact flitting through her mind like a swallow across a sky.”

Hamnet had a difficult childhood. His father was often away, and the boy had to navigate life around the “cutting, sharp, unpredictable” temper of a grandfather subject to “black humours”. Hamnet is a joyful child, depicted so lovingly by O’Farrell that a recreation of his death eviscerates a reader’s emotions more than four centuries later. Tragically, what Agnes fails to predict is that her son is in mortal danger from the Bubonic Plague. “All along she thought she needed to protect Judith, when it was Hamnet who was destined to be taken,” writes O’Farrell.

Hamnet, stricken with large and hideous buboes and soaked in the musky, dank, salty smell of this terrible disease, is “borne away like thistledown”. O’Farrell’s delicate description of the way Agnes and Shakespeare’s mother, Mary, prepare young Hamnet’s corpse for burial is haunting. The whole novel is overflowing with memorable imagery. “The grave is a shock. A deep, dark rip in the earth, as if made by the careless slash of a giant claw,” O’Farrell writes.

The Shakespeare family are all affected in different ways by the cruelty of fate. Agnes becomes unmoored, her mind adrift as she struggles to find a painless way to remember her talkative, restless, loveable son. His twin Judith is bereft. “I am only half a person without you,” laments Judith, who survived the plague.

Hamnet’s father, a man who had been subject to melancholy moods from a young age, retreats into the landscape inside his head, seeking an illusory release in writing about old battles and long-dead kings, inventing histories and comedies. “Only with them can he forget who he is and what has happened,” writes O’Farrell.

Things come to a head when Agnes finds out that Shakespeare has written a play with their son’s name in the title. “How could he thieve this name, then strip and flense it of all it embodies, discarding the very life it once contained?” she wonders. She heads to London to confront him. No spoilers, but I marvelled at O’Farrell’s entrancing, moving conclusion to his triumph of imagination.

Hamnet by Maggie O’Farrell is published by Tinder Press on 31 March, £20

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments