Why the Avatar saga might never be completed

James Cameron is continuing to make the most grandiose movies imaginable, even as the cinema-releasing landscape is changing around him, says Geoffrey Macnab

In the summer of 1997, there were terrible misgivings in Hollywood that film director James Cameron was about to blast a gigantic hole in the finances of two major studios. His blockbuster Titanic, which Fox and Paramount were co-financing, was over budget, over schedule and had just moved its release date from July to December. According to film trade paper Variety, the delay had cost Fox “an additional $20m or so in interest payments” to what was already the most expensive film ever made.

Media outlets were circling the project with the same morbid and ghoulish relish they always show when they sniff blood in the water. Reports and rumours were circulating of the director’s bullying, autocratic behaviour on set, of injuries to stunt performers, and of how the star Kate Winslet had allegedly caught pneumonia after spending too long in the freezing cold.

Winslet, who said she suffered hypothermia and nearly drowned twice, contemplated leaving the production, reported the LA Times. “You’d have to pay me a lot of money to work with Jim again,” she said.

The headlines were instructive. “The curse of Cameron”, “Going down with the ship?”, “Titanic sinks again”, and, most memorably, “Glub, Glub Glub” were among the ways the film’s supposedly dire predicament was summed up in the press. Memories were still horribly fresh of Waterworld (1995), the disastrous, big-budget post-apocalyptic action yarn starring Kevin Costner and industry pundits feared that Titanic would fare even worse.

In 2009, the same routine was repeated with Cameron’s next dramatic feature, Avatar. This film, which he was shooting in 3D, was even more expensive to make than Titanic and there were again dire prognostications about the damage the maverick and profligate auteur was doing to the delicate Hollywood ecosystem with his wastrel ways.

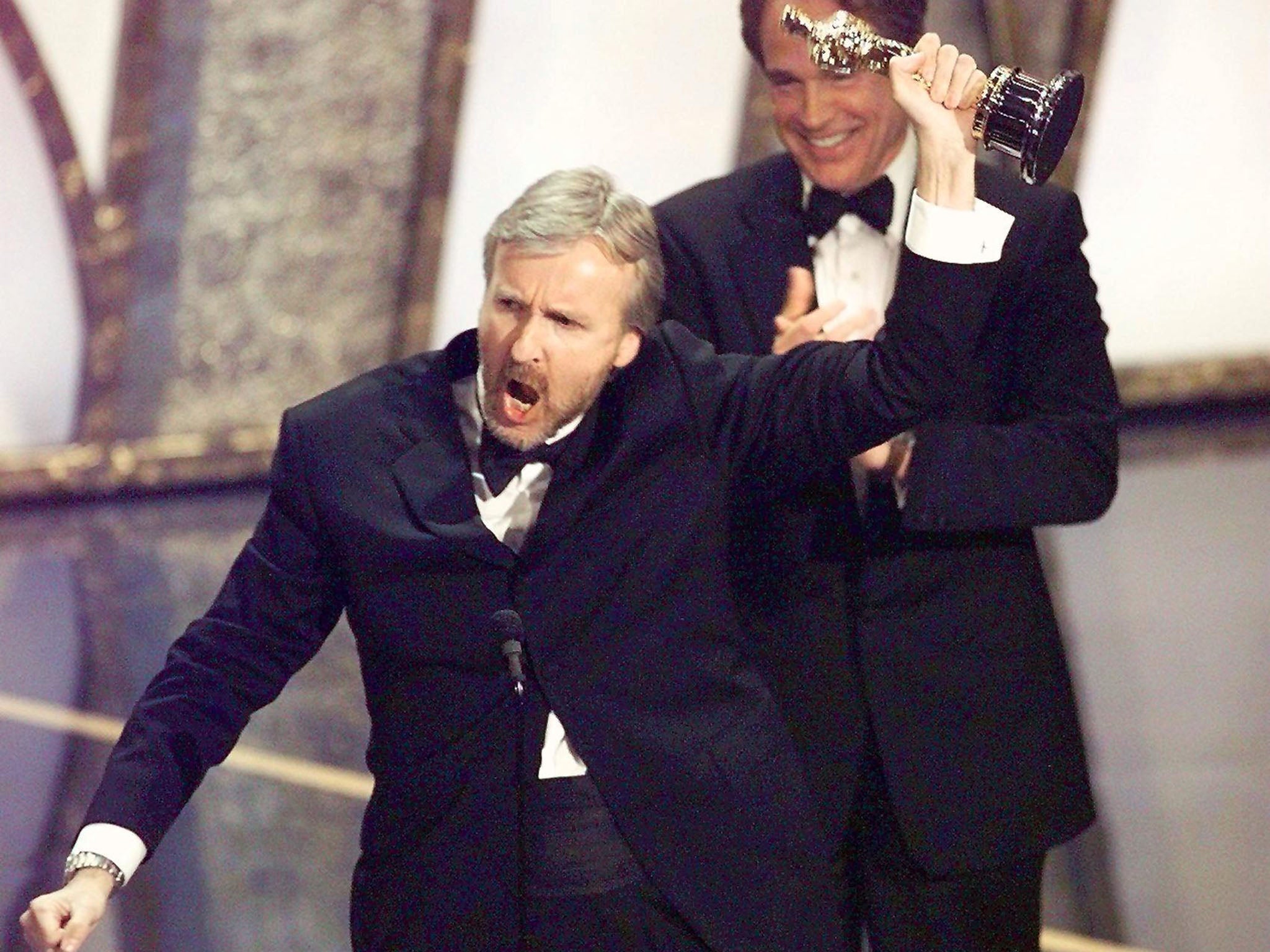

Of course, in both instances, the famously macho and belligerent Cameron was able to shove the criticisms right back down his detractors’ throats. There were two of the most commercially successful films of all time. The fact that they cost a fortune and were so painful to make was very quickly forgotten once the box office tills started ringing.

Not that the criticisms bothered Cameron. While other filmmakers might have been daunted by the whispering campaign against him and the very obvious desire many had to see him get his comeuppance, Cameron thrived on the antagonism. He worked best when the world was against him. He liked to view even his ostensible allies as his die-hard enemies. As studio executive Bill Mechanic, in charge of Fox at the time Titanic was made, told The New Yorker: “Even though he knew I was on his side, nobody’s ever on his side. It’s like you’re in the trenches and your infantry-mate is shooting at you, even if you’re the only one who can save his life.”

In the same interview, there were quotes from Cameron that made him sound like one of those madly obsessive, uncompromising heroes in Ayn Rand novels. “If you set your goals ridiculously high and it’s a failure, you will fail above everyone else’s success,” he declared.

Eleven years after Avatar, we are now back into the familiar Cameron dance. It’s again a case of the Canadian filmmaker against the world. He has made his feelings for the Hollywood studios clear by putting as much distance between them and himself as possible, working not in LA but far away in New Zealand on his long-gestating new feature, Avatar 2, and its various successors.

The global film industry has more or less ground to a halt during the Covid-19 crisis but Cameron, true to form, appears to see the pandemic as just another challenge for him to overcome. “It’s putting a major crimp in our stride here,” he told Empire magazine last month when he was at home in Malibu waiting to get back to New Zealand to resume shooting. However, by the end of May, he had already secured permission to re-enter the country.

As the New Zealand Herald reported, Cameron and many of his crew “touched down in Wellington through a little known loophole that allows foreigners through our closed borders”. The filmmakers were providing a significant boost to the local economy and were therefore allowed back into the country. They went into a 14-day government-supervised self-isolation period. Then, last week, they resumed shooting. The goal now is to have Avatar 2, the first of several planned Avatar sequels, ready for its 17 December 2021 release date. Avatar 3 will follow in December 2023, Avatar 4 in December 2025 and Avatar 5 in December 2027.

As the new Avatar films queue up like buses, the legacy of the first film in the series is not at all clear. Despite its enormous initial box office success, Avatar hasn’t had the same cultural impact as Titanic. Its actors aren’t revered in the way that Winslet and Leonardo DiCaprio were. Its much-vaunted special effects have been matched by those in many subsequent films.

Avatar was expected to usher in a new period of 3D storytelling on screen. However, the 3D boom hasn’t been nearly as extensive as originally predicted. This year, only a handful of major films are still being released in 3D.

The project’s real significance from an industry point of view is that it forced cinemas to move into a new digital era and signalled the demise of 35mm film projection. In its own way, the film was as influential as The Jazz Singer (1927) had been at the start of the talkie era. Hollywood had previously struggled to convince exhibitors, a notoriously conservative bunch, to convert to digital. This was going to be expensive, inconvenient, and time consuming. The attitude among many cinema owners was – why bother? However, when they realised they wouldn’t be able to share in the Avatar bonanza unless they adapted to the new technology, they quickly fell in line.

The irony is obvious. Cameron had always presented himself as being at war with the studios and yet he had ended up doing them an enormous favour with Avatar. His film paved the way for a new era of Hollywood blockbusters. He had shown that you could spend over $200m on a movie and still make monster profits. It was a lesson that Marvel Studios, in particular, picked up on as the scale and cost of their films began to rise and rise. The first film from the Marvel Cinematic Universe, Iron Man (2008), made the year before Avatar, cost a modest $140m but the reported budget for Avenger’s Endgame (2019) was $356m.

Cameron’s attitude towards Marvel is ambivalent. He offered his congratulations when Avengers: Endgame surpassed Avatar at the box office last year to become the top-grossing film of all time. But he also told film industry website Indiewire in a 2018 interview: “I’m hoping we’ll start getting Avenger fatigue here pretty soon … not that I don’t love the movies. It’s just, come on guys, there are other stories to tell besides hyper-gonadal males without families doing death-defying things for two hours and wrecking cities in the process. It’s like, oy!”

It’s clear that Cameron wants the Avatar sequels to restore him to his place at the top of the all-time box office charts. They have already reclaimed him the mantle of the director of the most expensive films ever made with a combined budget reported to be in excess of $1bn.

However, some believe that the golden age of modern-day mega-blockbusters may be nearing its end. For them to justify their enormous budgets, these films need instant access to audiences in every corner of the globe. Seventy per cent of the revenue for Avengers: Endgame came from overseas while the US accounted for only 30 per cent. The figures for Avatar were roughly similar: 72 per cent of the box office was generated in international markets. In a nervous post-virus world, it remains to be seen whether it will even be possible to give these kinds of films the saturation releases they need to achieve such astronomical box office numbers and to cover their production costs.

From the outside, it seems that Cameron is still going in one direction while Hollywood is heading in another altogether. He is continuing to make the most grandiose movies imaginable even as the cinema-releasing landscape is changing around him.

Just like Star Wars and Marvel, the Avatar sequels are being released by Disney, who took over from the projects’ original backers Fox last year.

Disney last year posted mind-boggling results for its films in cinemas. Thanks to films such as Avengers, The Lion King, Frozen 2, Captain Marvel, Toy Story 4, and Aladdin, Disney made over $13bn at the global box office.

Since then, though, the company has launched its Disney+ online service. Even without the coronavirus crisis, Disney has been tweaking its strategy, moving its emphasis away from the cinema and on to streaming. The traditional US theatrical “window,” the 90-day period in which films can be seen exclusively in cinemas, has come under intense pressure. Disney itself is making its films available digitally earlier than ever before. That doesn’t bode well for the Avatar sequels. Like all Cameron’s films, these will need to be seen on the biggest screens possible for both aesthetic and economic reasons. If they are going to claw back their $1bn outlay, they will need as much play in cinemas as they can get.

Last year’s Alita: Battle Angel, which Robert Rodriguez directed but which Cameron produced and co-wrote, hinted that the master might be losing his Midas touch. This was a Manga-inspired sci-fi action movie cluttered with so many visual effects that it looked closer to animation than it did to traditional live action. Audiences weren’t sure what to make of it. Alita didn’t even make it into the top 30 films at the US box office in 2019.

Can Cameron’s new batch of Avatar sequels repeat the phenomenal performances of Titanic and the first Avatar? From today’s vantage point, that seems a very tall order. Audiences are already punch drunk from far too many other VFX-driven blockbuster spectacles. It’s hard to see how Cameron can surprise them or trump what he has already achieved in Aliens, Terminator, and all his other films. Then again, this is one director who makes a habit of defying the most downbeat expectations. At his best, he is a consummate storyteller. People like his movies not just because of their size or groundbreaking special effects but because they are moved by them. If the Avatar sequels have enough of an emotional kick, his detractors might have to eat their words all over again.

‘Avatar 2’ is due to be released on 17 December 2021

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments