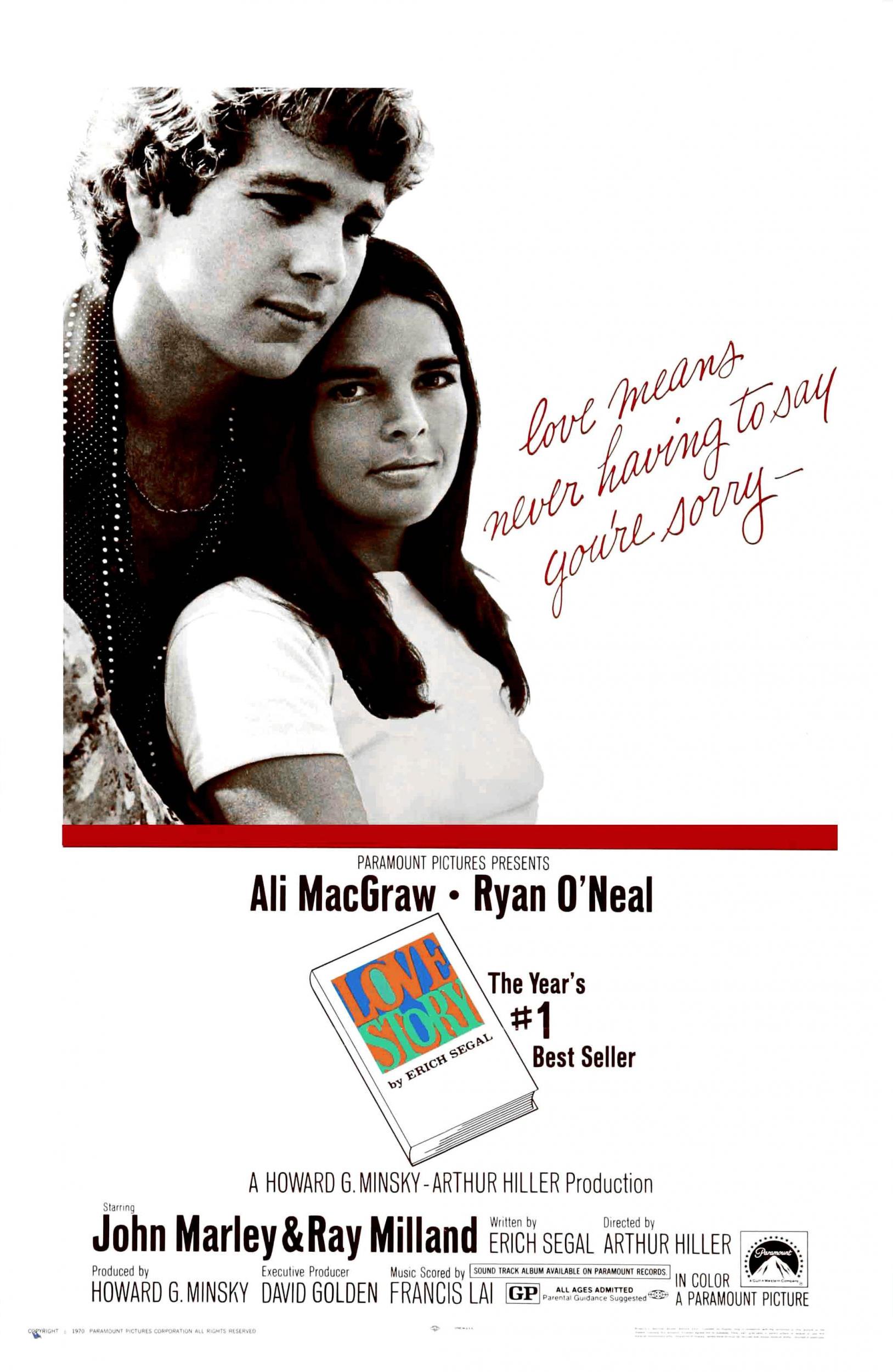

From Love Story to Fifty Shades: Why Hollywood no longer makes proper heartfelt tear-jerkers

‘Love Story’ is being re-released in the US this month in time for Valentine’s Day to mark its 50th anniversary, but when it comes to romantic dating movies in Hollywood, humour has now become their main ingredient, says Geoffrey Macnab

It’s half a century now since Yale classics professor Erich Segal, at the request of Paramount executive Peter Bart, agreed to write the novelisation of his own screenplay for the new movie, Love Story. The book, which Segal dashed off in under a month, appeared on Valentine’s Day, 1970, and the Arthur Hiller film followed 11 months later, the week before Christmas. Both were phenomenal successes, feeding off each other’s popularity.

Love Story, billed as “one of the most romantic films ever made”, has just been re-released in the US in time for Valentine’s Day to mark its 50th anniversary. However, it’s a sign of changing tastes in dating movies that the most successful Valentine’s Day film of recent times is Fifty Shades of Grey (2015). It made $570 million at the box office globally, roughly five times the $106 million haul, unadjusted for inflation, of Love Story.

Sam Taylor-Johnson’s adaptation of the EL James novel about the sadomasochistic relationship between Anastasia Steele (Dakota Johnson) and Christian Grey (Jamie Dornan) is poles apart from the Hiller film with its famous slogan, “Love means never having to say you’re sorry.” In Fifty Shades, the catchphrases tend to be about sex toys, blindfolds and safe words.

Some believe that Hollywood has now lost the knack of making romantic dramas. In today’s era of superheroes, dating apps and digital distraction, old-fashioned, emotion-driven movies for couples appear very anachronistic. “The idea of a tear-jerker becoming the number one picture seems surreal,” Peter Bart recently suggested.

Not that Love Story was an obvious commercial proposition anyway. Expectations about the project were initially very low. This was the time of Easy Rider and Woodstock, after all. A sappy yarn about “a 25-year-old girl that died” (the plot is given away in the very first line of the movie) and her romance with a preppie Harvard law student hardly fitted the spirit of the age. Love Story was made in precisely the period in which Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time in Hollywood is set but the world it depicts – snowy Ivy League campuses and dorm houses – is nothing like the dark, decadent post-summer of love world Tarantino shows us.

In the counter-culture era, many found the mawkishness in Segal’s screenplay hard to stomach. They didn’t want to be associated with a film that was so strait-laced. Peter Fonda, Jon Voight, Michael Douglas, Christopher Walken and Jeff Bridges were among the stars who reportedly turned the film down. This was, as Paramount’s ambitious young boss Robert Evans later remembered, “a picture no one wanted to be connected with”. Ryan O’Neal, a TV soap opera actor from Peyton Place, was eventually cast on the basis there were so few other viable candidates.

For months, Segal’s agent at William Morris, Howard Minsky, had failed to generate any interest whatsoever in his client’s screenplay. Minsky seemed to be the only one who believed in it. In the end, he grew so frustrated that he quit the agency and devoted himself full time to selling Love Story. Ali MacGraw, a rising young actor who had appeared in the Philip Roth adaptation, Goodbye Columbus (1969), had a deal at Paramount. She read the script “and cried”. Then Robert Evans, soon to marry her, got behind it.

The Paramount boss was painstaking in ensuring that Love Story worked. After the official shooting period was over, Evans pronounced the film “unreleasable” and sent the director Hiller and the two stars on a secret mission back to Boston to film extra material of the lovers frolicking in the snow and hanging out at different places in the city. He commissioned (and rejected) several different musical scores before eventually heading over to France to recruit Francis Lai, who had just written the music for Claude Lelouch’s A Man and a Woman. Lai’s syrupy Love Story theme, heavy on the piano tinkling and heart-tweaking strings, won an Oscar. This may have been schmaltz but it was extraordinarily well-crafted schmaltz. Its director Hiller, who had taken the job as a “filler” between two other films, was an unsung but proficient filmmaker who kept to budget and paid minute attention to character and performance.

Evans is celebrated for overseeing The Godfather and Chinatown and for revitalising Paramount at a time when the studio was on its knees. Without the success of Love Story, those later triumphs might never have happened. This was one of the most important as well as most derided films of its era. Some critics complained about the film’s “pussyfooting” approach and its blandness, the way it dealt with terminal illness and bereavement, without the two stars ever losing their Hollywood poise and glamour. Newsweek sneered that “the banality of Love Story makes Peyton Place look like Swann’s Way as it skips from cliché to cliché with an abandon that would chill even the blood of a True Romance editor.” Nonetheless, the film provoked a huge emotional response in audiences. Just as Segal wept when writing the final scenes of his own story, (some) hardened Hollywood executives couldn’t keep the tears away when first sent the screenplay, and cinemagoers also succumbed.

In his autobiography, A Kid Stays in the Picture, Evans writes about attending the premiere. “During the first hour, the silence was such that a single cough was an intrusion. Then seeping slowly through the theatre, a most peculiar sound began. All I could see was white. Cocaine? No – Kleenex! By the time the end credits began to roll the entire theatre was one white flag of surrender.”

As Peter Bart noted, audiences were “holding hands during the film; more important, they were holding each other after they left the theatre”.

There are certain superficial similarities between Love Story and Fifty Shades of Grey. Both are about relationships between a young woman from a humble background and a man from a world of power and privilege. At one point midway through Love Story, Jenny (MacGraw), sounding like Anastasia in Fifty Shades, jokingly calls her lover, Oliver Barrett IV (O’Neal), “master”. That’s when she visits his family, who live in baronial splendour in the countryside and make it clear that they disapprove of her lowly origins. (She’s the daughter of an Italian-American baker.) In both films, the women are made to suffer, albeit in very different ways, while the men look on.

The biggest difference between Love Story and the dating movies, steamy EL James adaptations and terminal illness melodramas that have followed it over the past 50 years is its complete lack of irony. The film deals with the romance between Jenny and Oliver and with her subsequent illness with heartfelt sincerity. We may see a young Tommy Lee Jones goofing around in the background from time to time as one of Oliver’s roommates, and Jenny may taunt Oliver occasionally, but this isn’t a film which otherwise demonstrates any obvious sense of humour.

“I think Love Story is going to start a new trend in movies; a trend toward the romantic, toward love, toward people telling a story about how it feels rather than where it’s at. I think Love Story is going to bring people back to the theatre in droves,” Evans boldly told the Paramount board. He was right about the latter part of his prediction. Cinema-going did increase. However, perhaps thankfully, Love Story didn’t usher in a new era of romantic weepies.

Segal’s reputation as an Ivy League academic never fully recovered from the tabloid exposure that Love Story gave him. Straight after the film was released, he was denied tenure in the Yale classics department, despite having been a professor since 1966. As his contemporary, cartoonist Garry Trudeau, said of him in an article in the Yale Alumni Magazine: “It wasn’t fair but you can’t dress up in tight leather pants to chat with starlets on Johnny Carson Friday night and expect to be taken seriously in a classroom Monday morning.”

Late in his life, the screenwriter published a very hefty book called The Death of Comedy, which he had spent a quarter of a century writing. It’s a wide-ranging study that takes in everything from classical comedy to Hollywood slapstick, citing figures from Aristophanes to Shakespeare, Samuel Beckett, Buster Keaton, Charlie Chaplin and Stanley Kubrick.

In his conclusion, Segal argues that after “the savage atrocities” and “mass slaughters” of two world wars, there wasn’t much left for comedy to engage with beyond “nuclear holocaust”.

The book was respectfully reviewed even if many critics argued that, as the The New York Times put it, “comedy wilts instantly under the glare of interpretation”.

Segal may have pronounced the death of comedy but when it comes to romantic dating movies in Hollywood, humour has now become their main ingredient. Instead of the earnestness of Love Story, we have the high jinks of Amy Schumer and Judd Apatow. Even Fifty Shades has its share of kinky jokes. Lines between romcoms and romantic dramas, which used to be two distinct genres, have blurred. There are still occasional terminal illness melodramas (John Green adaptations such as The Fault in Our Stars or the Emilia Clarke vehicle Me Before You, in which, for once, the man dies.) However, proper tear-jerkers like Love Story that once turned cinema floors into seas of discarded Kleenex are now in very short supply indeed.

‘Love Story’ is available on Amazon Prime

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments