Camp, ironic, extravagant: How Diamonds Are Forever irrevocably changed James Bond

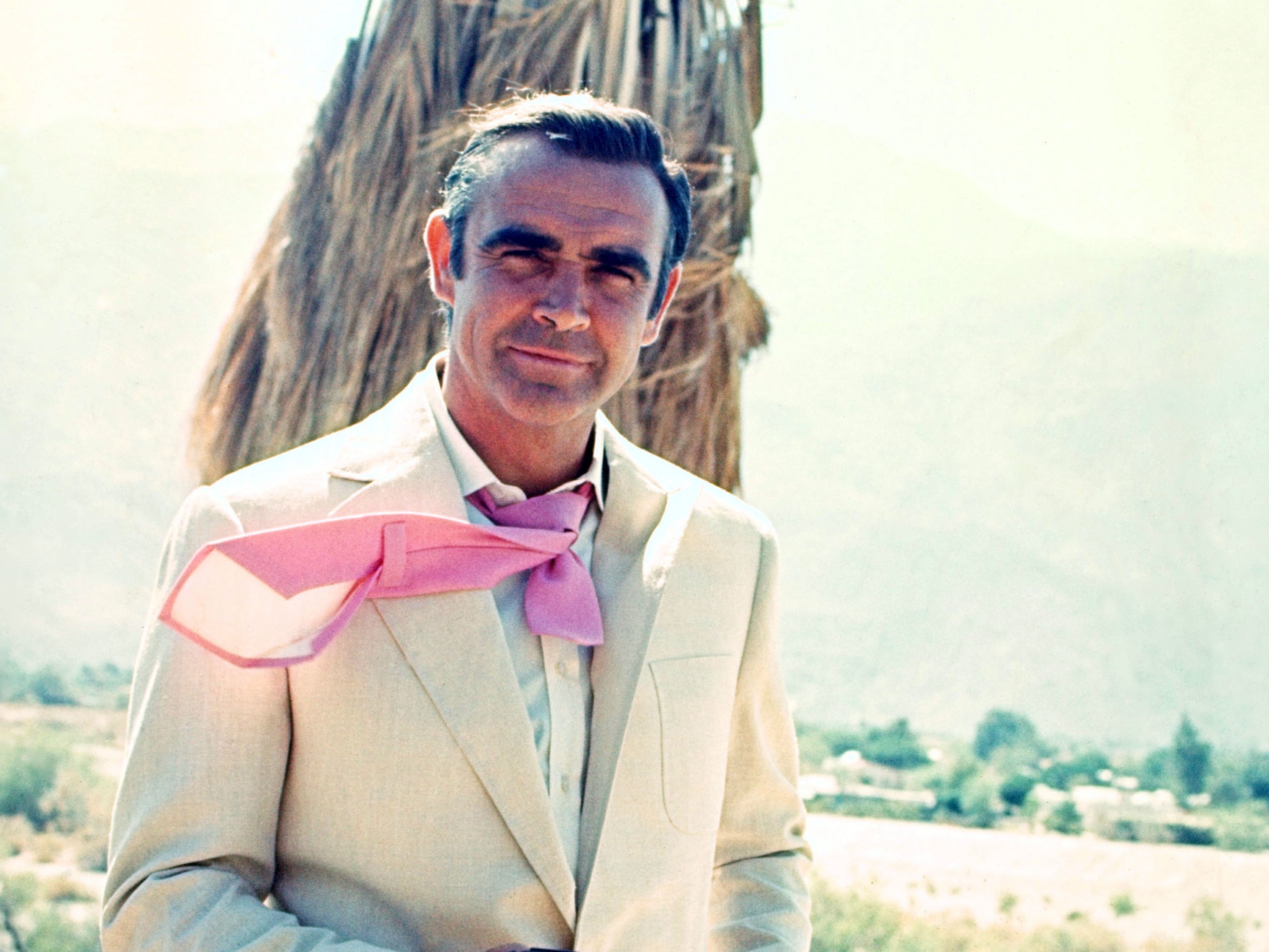

It’s the 50th anniversary of Sean Connery’s final Bond film, one of the most playful and idiosyncratic in the franchise. Geoffrey Macnab looks back at how the movie served as a turning point in the evolution of the world’s most popular screen spy

Speaking this week, writer-director Andrew Birkin says he can’t remember “much that will be of interest” about Diamonds Are Forever (1971), “having only spent a few days at Pinewood doing second-unit directing (if one can call it that) with Blofeld’s white cat”. However, his reminiscences give a flavour of a movie that changed the direction of the James Bond franchise forever.

Birkin’s job was to shoot inserts of the cat. “I remember that it had a fake diamond collar,” he says of the furry white Persian, which he filmed leaping off a sofa, sitting purring on a desk and being petted by arch-villain Ernst Stavro Blofeld.

While the film’s director Guy Hamilton, star Sean Connery and the rest of the team were busy on an adjoining set, an increasingly frustrated Birkin was on cat duty, working with the animal, its trainer, a Blofeld double and occasionally the real Blofeld himself (Charles Gray).

“They’re always quite tricky, those animal trainers,” says Birkin. “You have the trainer that comes with the cat and you relay instructions to the cat via the trainer. It was a pain in the neck and that was why Guy Hamilton handed the job to me.”

The film, which celebrates its 50th anniversary this year, marks the moment when Bond ceased being the “quiet, hard, ruthless, sardonic, fatalistic” figure described by Ian Fleming and which the original Bond screenwriter, Richard Maibaum, had worked hard to preserve.

Two major changes were occurring to Bond during Diamonds Are Forever. One was the accelerating shift toward the extravagant, self-parodic humour that would characterise the later Roger Moore 007 films. Blofeld’s cat was part of this transformation. In a famous scene, confronted by Blofeld and his doppelgänger, Bond kicks the furry creature to see where it will go and then shoots the man whose lap it lands on. A second cat wanders into view and Bond realises he has killed the wrong Blofeld.

This was the film in which Blofeld dresses in drag and in which Bond races across the Nevada desert in a space buggy. It’s the one with all the plot devices that would have been dismissed as too far-fetched in the Austin Powers spy spoofs made by Mike Myers.

Bond was also being (at least partly) Americanised. Except for one or two preliminary scenes in London and a memorable interlude in Amsterdam where the spy goes under an assumed identity for his first meeting with Tiffany Case (Jill St John), the entire film plays out in the US – and largely in Las Vegas.

There was an obvious symbolism in bringing Bond to Vegas. It was where big stars went when their managers wanted to cash in on them. Elvis had a residency there; so did Frank Sinatra and Tom Jones. Now it was Bond’s turn.

The “bright light city” provided obvious opportunities, but it also suggested a lack of creative imagination. While Vegas offered entertainment value – in the form of circuses, casinos, showgirls, and British secret service boffin Q (Desmond Llewelyn) using magnets to rig the fruit machines – it was all very generic.

There had long been a paradox about Bond on screen. He was a quintessentially British spy in a movie franchise produced by an American (Cubby Broccoli) and a Canadian (Harry Saltzman) and bankrolled by a Hollywood studio.

Diamonds Are Forever’s predecessor, On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (1969), which starred George Lazenby, had underperformed at the American box office and the producers were determined to get the US audiences back on side with their next film.

Screenwriter Tom Mankiewicz, the son of All About Eve director Joseph L Mankiewicz and nephew of Herman J Mankiewicz (the “Mank” in David Fincher’s recent award-winning movie), had therefore been drafted in. “I want to have an American writer because it takes place in Vegas and the Brits write really lousy American gangsters,” Broccoli told the young writer.

Bond himself had come perilously close to being played by an American. Scottish star Connery had sat out On Her Majesty’s Secret Service even though it would have given him a rare chance to play the character in a kilt. He didn’t want to come back. Nor had the producers wanted him back. They had already given a contract to John Gavin, the strapping American actor from Psycho.

However, United Artists boss David Picker offered Connery an astronomical amount of money – and he took it (later giving his fee to the Scottish International Educational Trust). Gavin’s contract was quietly paid off. An ardent Republican, he went on to serve as President Reagan’s ambassador to Mexico. “He is certainly a good ambassador. He might also have made a first-class Bond,” Broccoli wrote in his autobiography with evident regret.

As Mankiewicz conceded, the Ian Fleming novel on which Diamonds Are Forever was ostensibly based “probably coincides with the movie for 45 minutes out of its two-hour ten-minute running time”.

“Fleming’s stories were tailored for the light read. They were never constructed with films in mind. Which is why we have to build on them, restyle them for the age of lasers, computers, space travel and genetic engineering,” was how Broccoli justified the cavalier approach to the source material.

The plotting was on the baffling side. Locations range from dirty South African diamond mines to the further reaches of outer space. The precious jewels are hidden everywhere, from inside the mouths and boots of the miners to around a chandelier in Tiffany Case’s Amsterdam apartment. They also end up on the tip of a galactic laser weapon with which Blofeld threatens to destroy the world.

For reasons which remain hard to fathom, the denouement plays out on an oil rig.

At every juncture, Mankiewicz fills the film with acerbic, witty lines that you would more commonly expect to find in one of his father’s sardonic Hollywood comedies with Bette Davis.

“As La Rochefoucauld once observed, Mr Bond, humility is the worst form of conceit. I have the winning hand,” Blofeld sneers, referring to the 17th-century French moralist and author. Mankiewicz remembers that Broccoli was completely bewildered by such a literary reference.

Some of Mankiewicz’s puns were also far too much for Broccoli. When the diamonds are smuggled inside the anal cavity of a body in a coffin and CIA agent Felix Leiter (Norman Burton) wants to know where they are, Connery tells him: “Alimentary, my dear Leiter.” The producer tried to have the line scrubbed but Hamilton insisted it be left in.

The world had been changing since 007 had last tussled with Blofeld in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service. The Sixties were over. The new Bond movie started shooting in April 1971, the month Charles Manson was sentenced to death (a verdict later reduced to life in prison). One might have expected the film-makers to acknowledge social and political shifts. Instead, they blithely ignored them. The women are still generally treated abominably. Early in the film, Bond tells Marie (played by Denise Perrier, a former Miss World) that “there’s something I’d like you to get off your chest”, rips away her bikini top and throttles her with it until she reveals Blofeld’s whereabouts. Plenty O’Toole (played by Natalie Wood’s sister Lana) is casually tossed out of a top-storey window – by chance, there’s a swimming pool below. The high-kicking bodyguards Bambi and Thumper (Lola Larson and Trina Parks) are nearly drowned by Bond. At one stage, Bond slaps Tiffany. Such scenes wouldn’t be countenanced today.

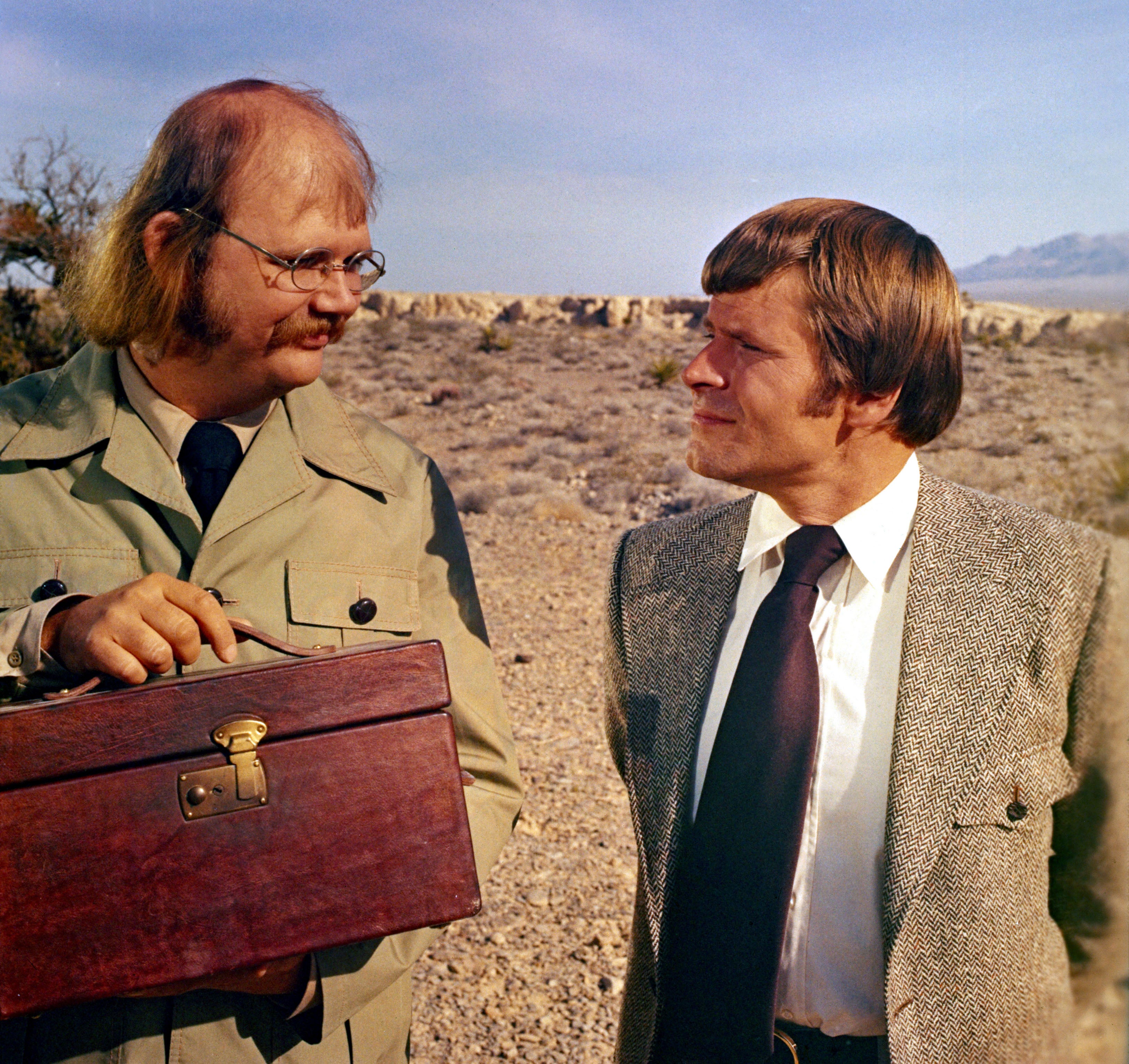

Meanwhile, the portrayal of the gay, hand-holding villains Mr Wint and Mr Kidd (Bruce Glover and Putter Smith) is openly homophobic. Bond gags at the overwhelming smell of their aftershave and recoils at their mannerisms. There is a strange coda aboard an ocean liner in which Wint and Kidd pretend to be waiters. They’re serving an extravagant dinner to Bond and Tiffany Case with a bomb for dessert but betray themselves at the vital moment because they know even less about fine wine than Robert Shaws’ Spectre agent did in From Russia With Love.

The storytelling is cartoonishly repetitive. Again and again, Bond is caught in a near-lethal predicament: locked in a coffin in a crematorium, stuck in a lift or trapped in a pipe under the desert with only a rat for company. Every time, he escapes, brushes his suit or tuxedo down and carries on as if nothing has happened.

Nevertheless, the film achieved its goals. It was a huge box-office success and recaptured the American audience who hadn’t bought into Lazenby as Bond in its predecessor. In its own scattergun way, it remains highly entertaining: full of chases, fights, witty repartee and exotic locations.

“It was a very enjoyable film even though it wasn’t remotely scary and you don’t think for a minute that Bond was in any danger whatsoever,” Birkin reflects. “Retrospectively, I think it was almost too tongue in cheek.” His opinion may be jaundiced by his less than affectionate memory of Blofeld’s cat, but he makes a fair point.

Daniel Craig, whose much-delayed next Bond film No Time to Die is now due to be released in October, has brought back some of the old ruggedness to the character, but something happened to Bond in Diamonds Are Forever that can’t be undone. Fifty years on, Diamonds Are Forever looks like a turning point in the evolution of the world’s most popular screen spy. It was the moment he went to Vegas. Like Elvis and Sinatra before him, he would never be quite the same again.

Diamonds Are Forever is available on Amazon Prime

‘No Time to Die’ will be released in October, Covid restrictions permitting

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks