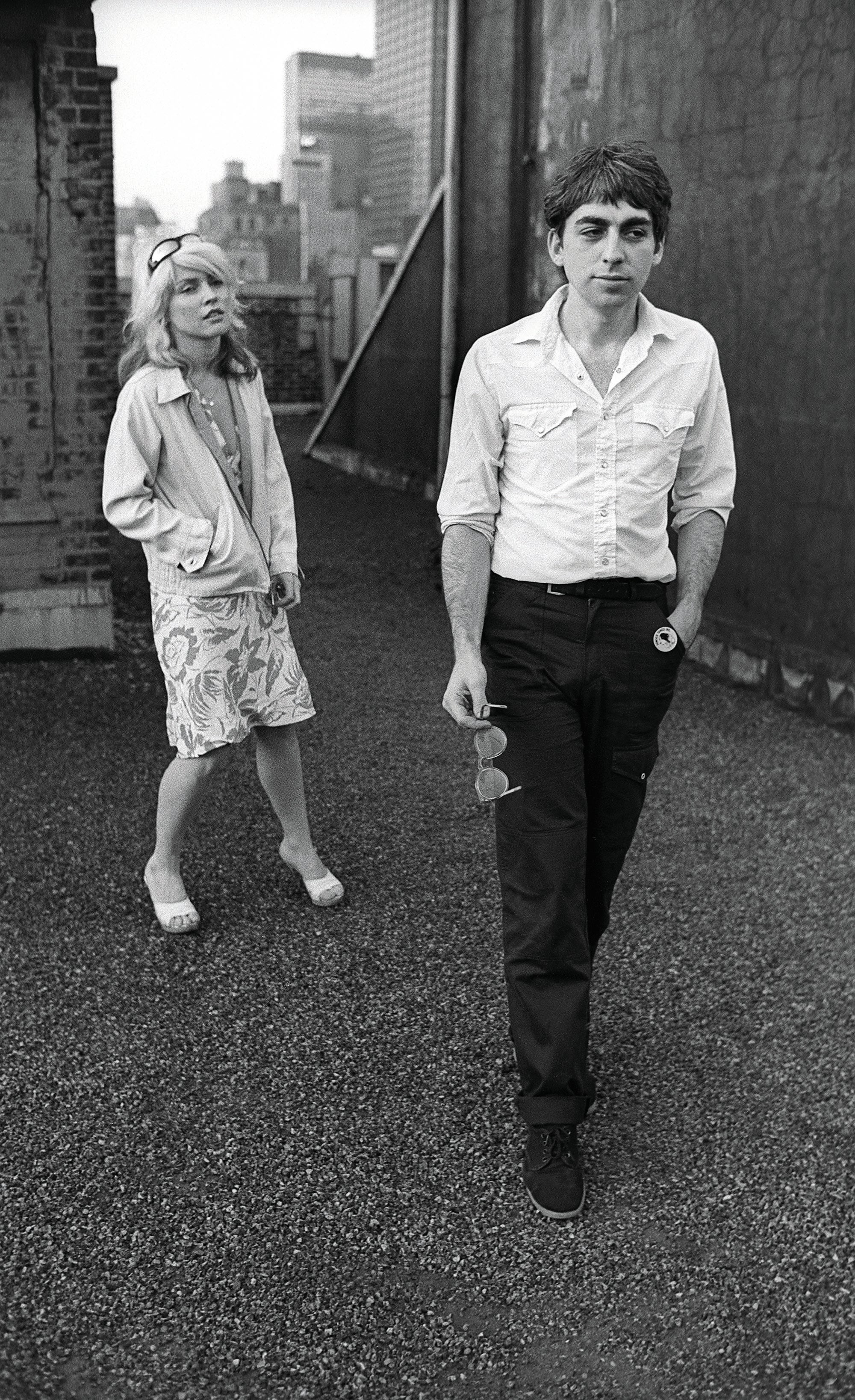

Blondie’s Chris Stein on Debbie Harry, addiction and losing the people he loved the most

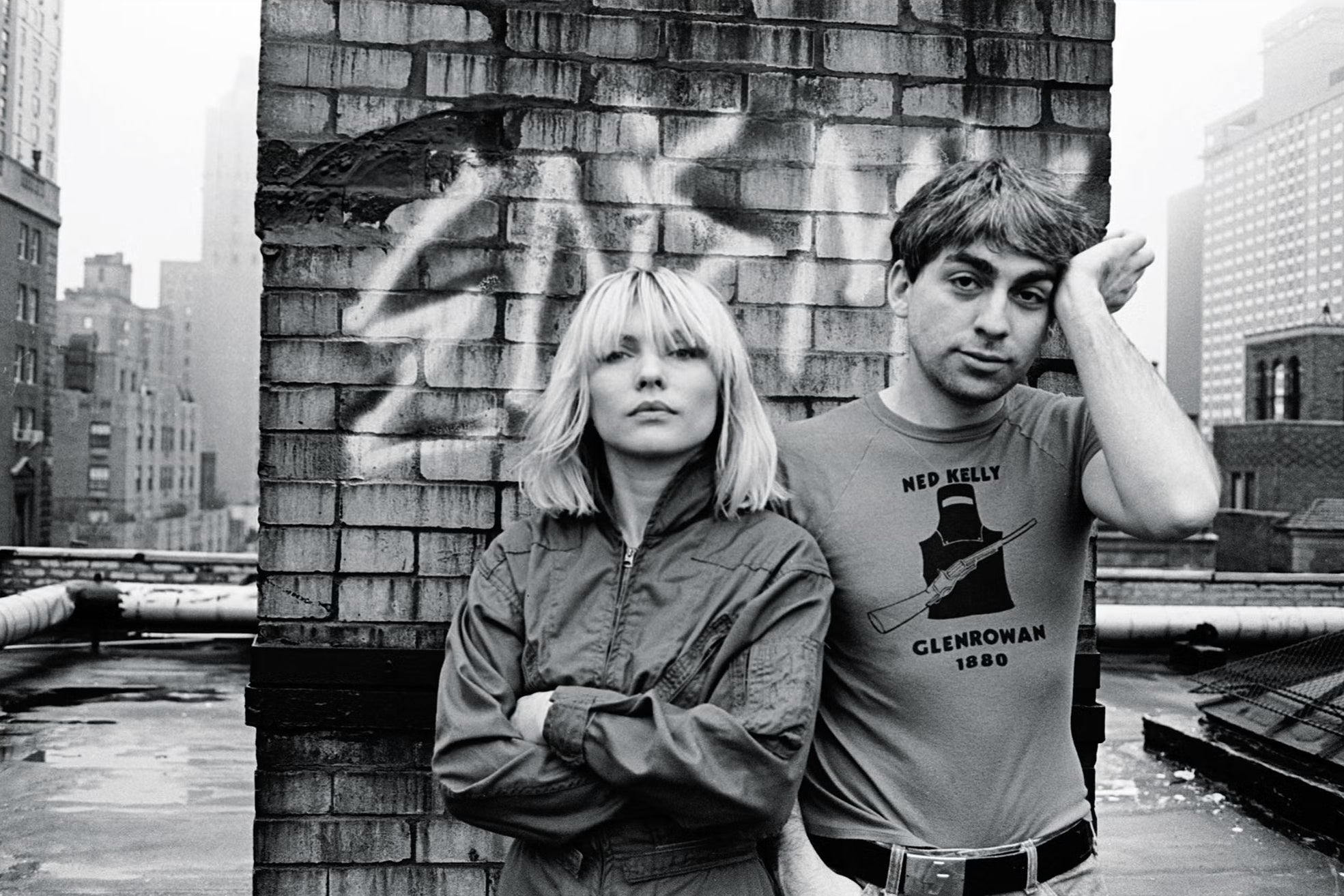

Together with his bandmate and ex-girlfriend Debbie Harry, the Blondie guitarist became a cornerstone of rock and roll in Seventies New York City. He sits down with Jim Farber on the release of his tell-all memoir, which spares no gory details on a wild and reckless life

If you want to make Chris Stein laugh, ask him how he feels about the latest view that New York City has become nearly as violent today as it was when his band Blondie emerged from its sooty streets in the 1970s. “That’s crazy!” Stein, now 74, says with a snort. “You know how today you can have that Citizen app on your phone that tells you the bad things that are going on in your neighbourhood? If you had one of those things in the New York of the Seventies and Eighties, it would be like turning on a faucet. You’d never hear the end of the mayhem.”

Small wonder parts of Stein’s riveting new memoir, Under a Rock, read as much like a crime novel as a musical biography. Like the day in 1975 when he and girlfriend Debbie Harry casually stumbled across a corpse in the doorway of the dilapidated building they lived in on the Bowery. “Some poor bastard had frozen to death on the street,” Stein says now.

Or the night he was walking across the Manhattan Bridge when he saw a young man sprawled on the pavement, dead from a gunshot to the head. “I kept going and never found out what had happened,” Stein says. Or the several times he chatted amiably with Daniel Rakowitz, who later became infamous for chopping up his girlfriend and storing her rotting skull in a plastic bucket of kitty litter. “He seemed like an OK guy to me,” Stein says with a shrug.

For Blondie, such grit was key to shaping their sensibility as a band. Along with their role as musical innovators – they famously married the warring factions of disco and punk on “Heart of Glass”, and integrated rap with new wave on “Rapture” – Blondie helped bring the aesthetics and humour of trash culture to the top of the pop charts.

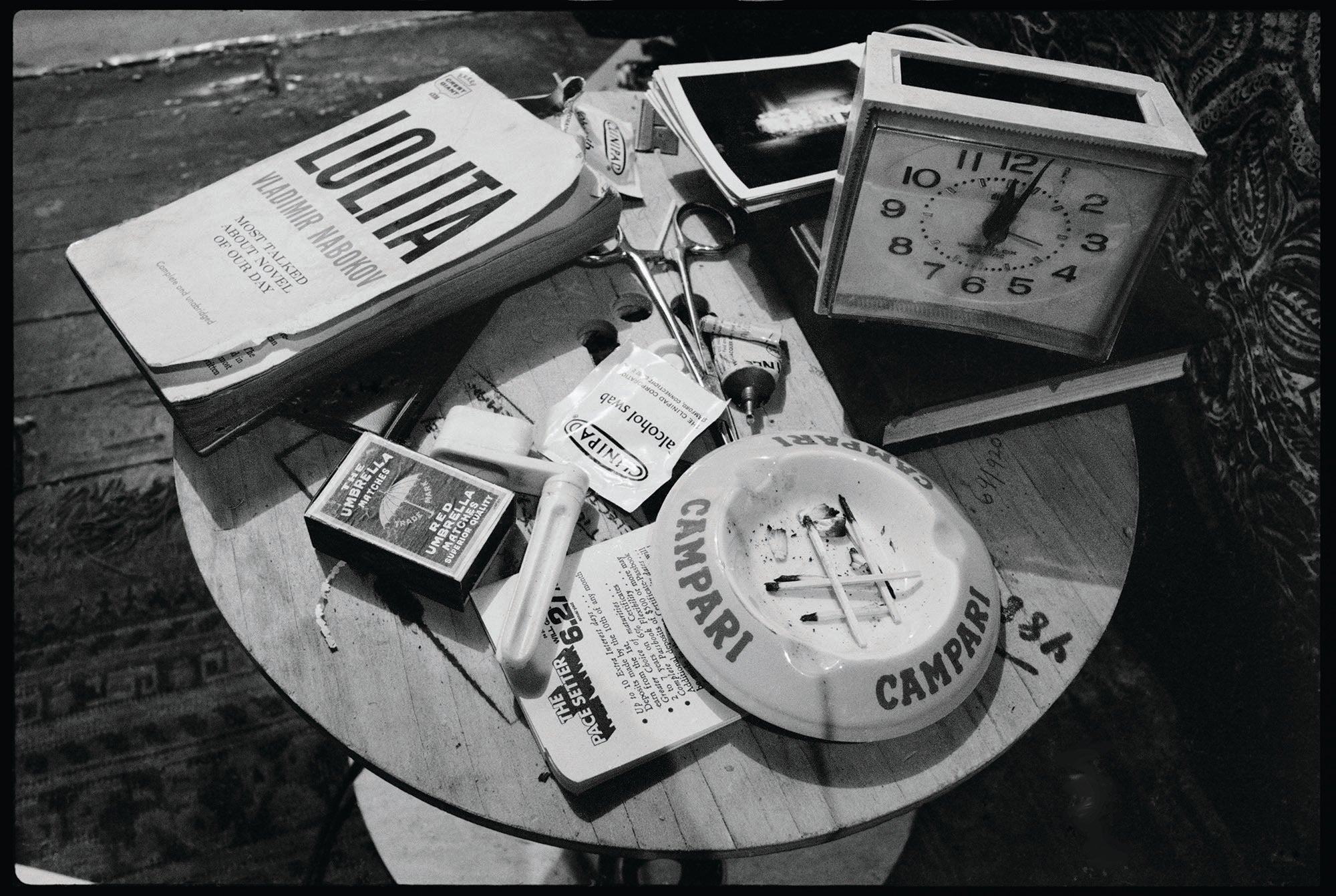

The result made them enormously popular, soaring Harry to international sex symbol status in the process, but Stein’s story includes addiction to drugs from a young age, including methadone and cocaine, which he freebased. In 1983, he suffered from a mysterious, near fatal disease and, later, endured a prolonged stretch of poverty that, ironically, came smack on the heels of the band’s greatest triumphs.

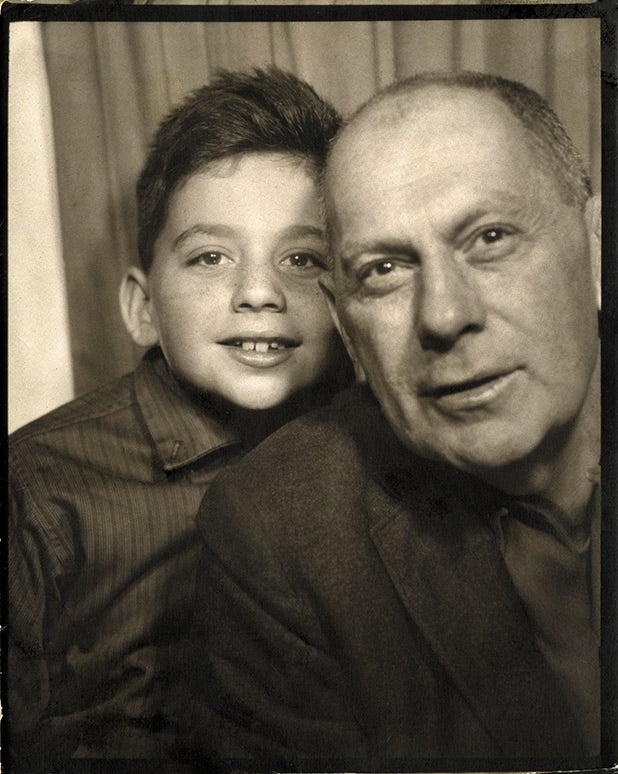

Speaking about that now, Stein keeps coming back to the same refrain: “It was a different time then.” That’s obvious from the setting of our interview at Stein’s apartment in the far West Village. Once a desolate part of town often used by gay men for public sex, it’s now arguably the most coveted part of the city. It’s light years from Stein’s working class rearing in Coney Island, where he was raised by Holocaust-generation Jewish parents who identified as communists.

At 13 years old, Stein was already making a habit of sneaking into shows in Greenwich Village by stars like Stan Getz (his first concert) and The Blues Project. In his teen years, he was everywhere a rock fan could dream of being, from catching the Velvet Underground at their Exploding Plastic Inevitable start, to driving with friends to San Francisco during the summer of love.

By 16, he was deeply into psychedelic drugs, leading to a mental breakdown that doctors tried to treat with Thorazine with varying degrees of success. Back in New York, he drifted around the city in a haze while playing with other proto-punk musicians seeking a sound. He auditioned for Richard Hell’s early band The Neon Boys but was rejected for being “too nice”.

In 1973, he met Harry, then 28, five years his senior, whom he hit it off with musically as well as romantically. “I thought, ‘She’s so charismatic and she’s a good singer too,’” Stein recalls. “I saw what everybody saw – but earlier.”

The two formed a glam-rock-influenced band called The Stilettos that kept getting into scrapes. One night after a gig, they were attacked in Stein’s apartment by a guy who tied them up separately, robbed them and raped Harry. “All these years later, I still want to kill this person,” Stein writes in his memoir. At the time, however, the couple didn’t even report the incident to the police. “It just seemed pointless,” Stein says. “I had [another] girlfriend who had been raped and beaten. She was in hospital when the guy came up for trial, so they just let him go. That kind of stuff happened all the time then.”

Stein suggests it’s hard for young people to fathom a world in which he and Harry maintained what he calls a “goes with the territory” attitude towards violent crime in the city. “With all the focus on ‘safe spaces’ today, they wouldn’t understand,” he says.

Blondie was always at the bottom of the A-list

Things were different, too, in the music industry. It wasn’t long after forming Blondie in 1974 that Stein and Harry started getting attention at the now iconic music club CBGB in the East Village. Even so, they weren’t courted by the coolest label of the day, Sire, which instead signed the Ramones and Talking Heads from the scene. “Blondie was always at the bottom of the A-List,” Stein says. “Everybody liked us, but nobody thought we would be successful.”

They did get an offer from Private Stock, a label known mainly for novelty songs like the Walter Murphy disco hit “A Fifth of Beethoven”. But the deal Blondie signed was so awful it earned them an advance of just $800. Why did he go along with such a terrible contract? “I smoked a lot of pot and trusted a lot of people,” Stein says.

By contrast, the music Blondie made on their 1976 self-titled debut was focused, catchy, and hilarious. Much of the music on that first record was influenced by the girl groups of the early Sixties, mimicking the grand arrangements, and melodramatic lyrics, shaped by producers like Phil Spector for teen acts from The Ronettes to The Shangri-Las. Surprisingly, Stein says he was anything but a fan of that sound as a kid. “I saw The Shangri-Las as novelty music, the same way I see Justin Bieber now,” he says. “But when I started working on music, I started to realise how genius it was, and I completely flipped.”

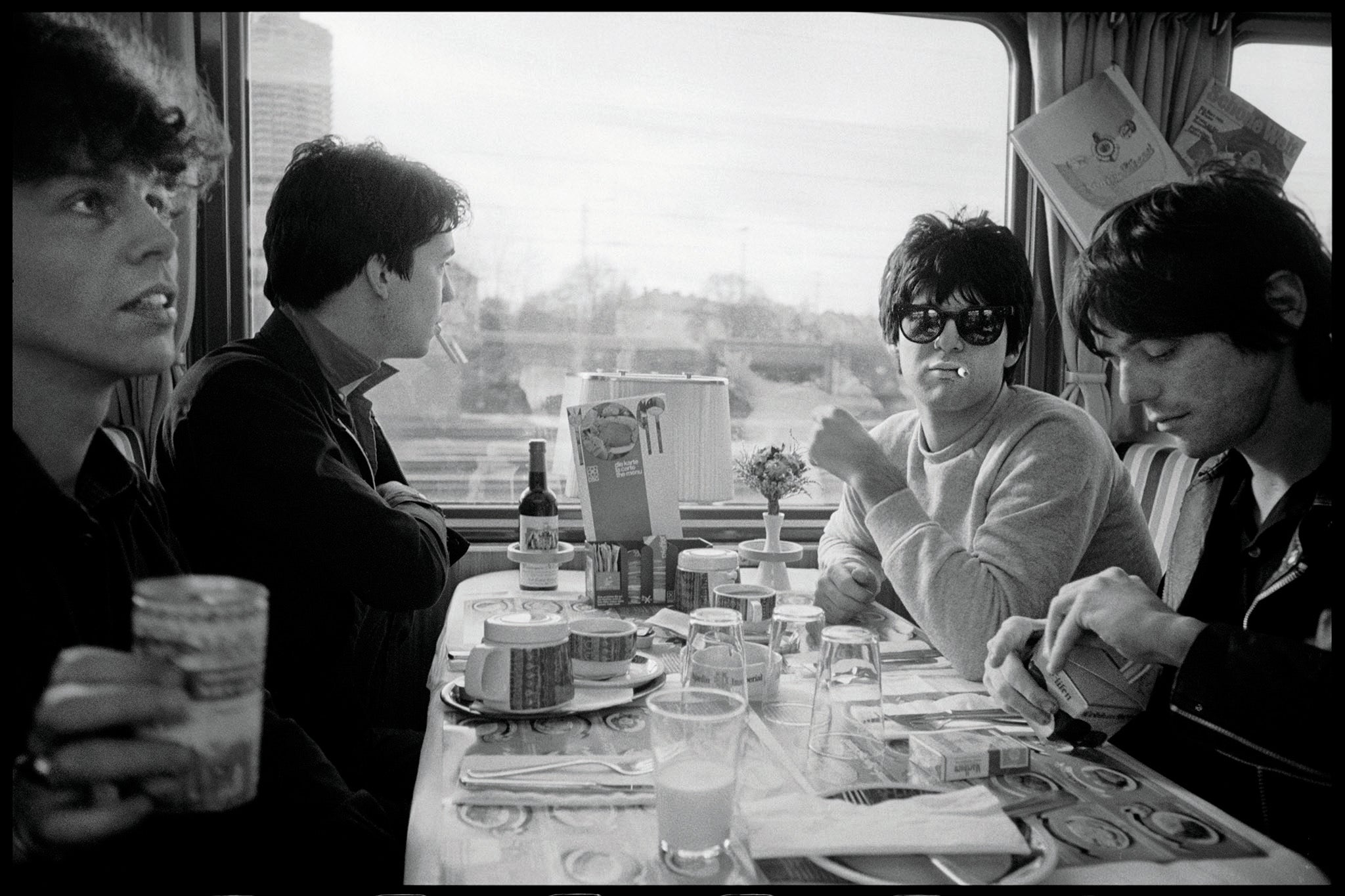

By their second album, Blondie secured a new deal with Chrysalis Records, which led to breakthroughs in the UK and Australia before the US. When Blondie hit London, it was during the of that charming trend in which fans showed their affection by spitting on performers while they played. Harry asked them to stop because spit “doesn’t go with my dress”.

She had just as tart a response to David Bowie when, in front of Stein, he asked Harry: “Can I f*** you?” “I don’t know,” she replied. “Can you?” Her cheeky response charmed Bowie and the come-on didn’t bother Stein in the least. “Me and Debbie were pretty loyal to each other,” he says. “I had girls coming on to me, too.”

There was tension, however, among the other band members over the fact that Harry got far more press attention than they did. Stein didn’t care, he says, because her appeal “was obvious. She was gorgeous”.

Already, though, they had issues with that manager, who was given to telling the members they were all replaceable, including Harry. “Let’s just say the guy didn’t have good people skills,” Stein says. He was hardly the only clueless person in their camp. In 1978, when Blondie submitted their album Parallel Lines to Chrysalis, the label initially rejected it. The record went on to hit No 1 in the UK, spurred on by such enduring singles as “Heart of Glass” and “One Way or Another”. Only the protestations of their powerful producer, Mike Chapman, forced the label to release it as it was.

I was probably pissed for a couple of weeks, but it didn’t last. We stayed friends

Likewise, when Blondie submitted their Autoamerican album in 1980, Chrysalis said they couldn’t hear any singles on it. Two of its songs later crowned the American charts: “The Tide Is High” and “Rapture”. The latter becoming the first single with a rap verse to reach No 1 in the US. Harry and Stein were famously early in recognising the importance of the hip-hop scene that was happening way uptown at the time. “But it was just so f***ing exciting”, says Stein. “It reminded me of what was going on musically downtown [within the world of punk].”

Blondie went on to enjoy huge success, but the pressure contributed to Harry and Stein both becoming heroin addicts, which eventually led to the end of the band in 1982, less than 10 years after they formed. Their romantic relationship ended as well, though Stein says there wasn’t much drama to it. “I was probably pissed for a couple of weeks, but it didn’t last,” he says. “We stayed friends.”

Though Harry cleaned up from drugs relatively quickly, Stein stayed addicted for decades. Because of the terrible deals he made, and a crooked accountant, he had so little money from Blondie’s success, he wound up living in a squat. In the intervening years, Stein sold the townhouse he once owned on the Upper East Side, as well as original paintings by friends Jean-Michel Basquiat and Andy Warhol for a fraction of what they were later worth.

He also began to waste away from a disease many thought was Aids at a time when that scourge was at its height in New York. In truth, he was suffering from a rare autoimmune disease called pemphigus vulgaris, which was eventually treated successfully with steroids. Terrifying as the experience was, Stein says, “it was also illuminating. I looked inward”.

People aren’t responding to the opioid epidemic the way they should

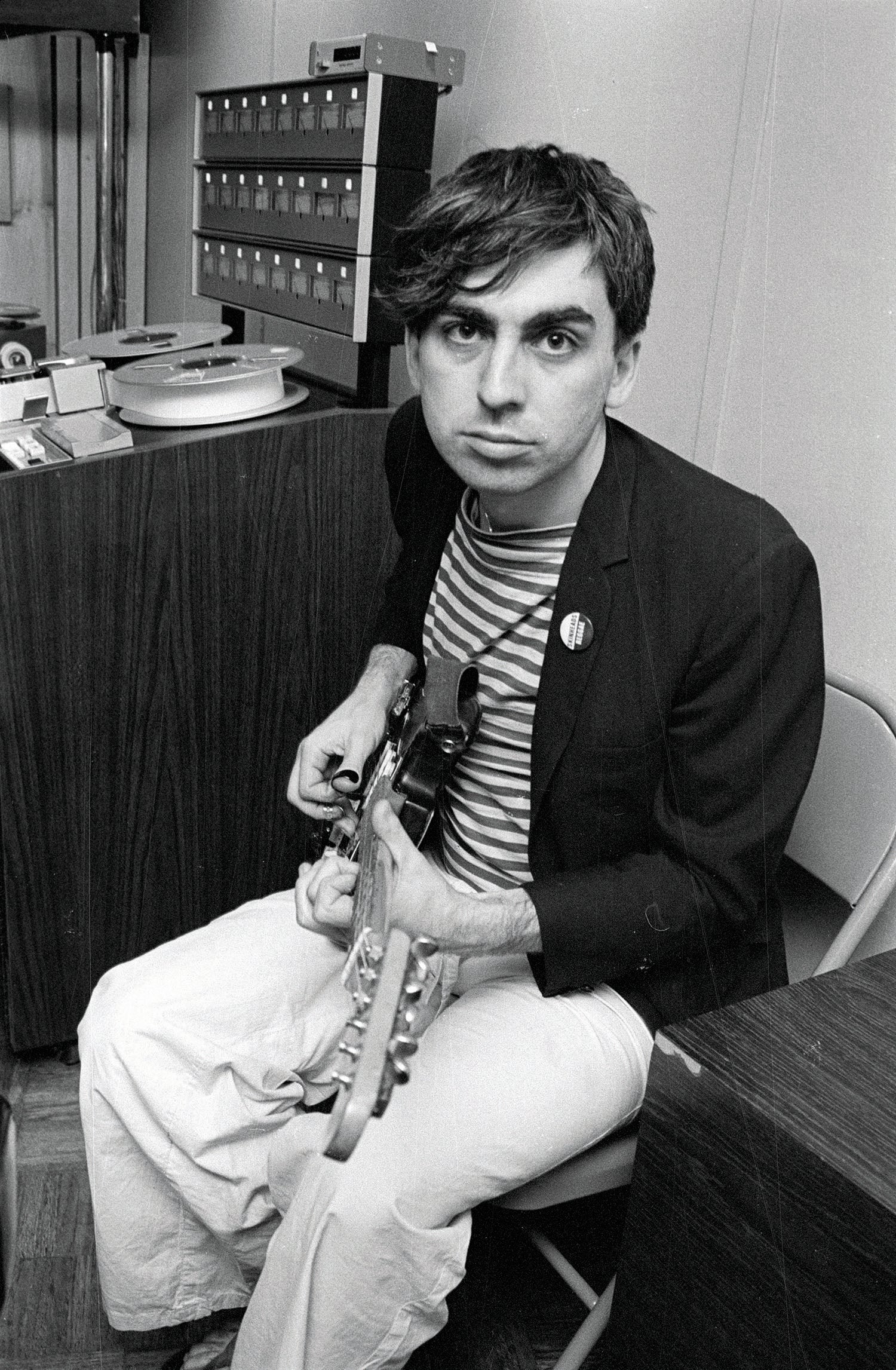

He now talks about his impoverished years with a certain wonder. Part of that likely comes from his role as an observer, evidenced by both his songwriting and his street photography, which he began in earnest in the 1960s. The results of the latter have been published in several books over the years. Things didn’t begin to turn around for Stein until 1997, when Blondie reformed, leading to the successful comeback album No Exit and a No 1 hit in the UK with “Maria”. Today, Stein is financially comfortable enough to live in the West Village with his wife of 25 years, the actor Barbara Sicuranza.

Despite that happy turn, the last part of the book chronicles a litany of loss as Stein watches his circle of friends die off, from Basquiat to Warhol to every member of the Ramones. “It was all too soon, and so sad,” he says, his voice trailing off from the collective weight of it. The most searing loss of all came last year when one of his two daughters died from an opioid drug overdose. She was 19. “It’s a f***ing epidemic,” Stein says.

In the context of all this tragedy, Stein reflects on his own issues and says he feels lucky to be alive. He no longer tours with Blondie due to his AFib, a heart condition that saps much of his energy. He spends the duration of our interview reclined in his chair. Even so, he has managed to work with the band in the studio, resulting in a new album that’s slated to appear by year’s end.

Despite the many lows he recounts in the book, there are few regrets and Stein eschews judgement and sentimentality at every turn. Instead, he honours the classic New York ethic of accepting things as they are. “I try to maintain my optimism,” Stein says. “It’s a struggle sometimes. But it’s what you have to do.”

‘Under a Rock: A Memoir’ by Chris Stein is out now, published by Corsair

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks