Books of the month: From Pity by Andrew McMillan to The Fetishist by Katherine Min

A new novel from Howard Jacobson, the insightful diaries of women across the ages, and Paul Theroux on George Orwell’s time in Burma – Martin Chilton picks the best reads for this month

Older book lovers who visited or grew up in central London may well have fond memories of Silver Moon, the defiant women’s bookshop on Charing Cross Road, founded in 1984, which sold radical and feminist books in an era of rampant homophobia and misogyny. Jane Cholmeley, one of the co-founders, tells its intriguing 17-year history in A Bookshop of One’s Own: How a Group of Women Set Out to Change the World (Mudlark). There are highs – including a delightful signing session by Margaret Atwood – and some lows, including a court battle with a petty Westminster Council and the dubious career delight of “having to clean the carpet from a w**ker’s sperm”. A Bookshop of One’s Own is funny and warm.

The spectre of Donald Trump as president is back and so it seems timely to look at two books in which the dangerous orange oaf features. John Rennie Short, emeritus professor at the University of Maryland School of Public Policy, takes an (unduly, I fear) optimistic view about the “fading” political future of Trump. In Insurrection: What the January 6 Assault on the Capitol Reveals about America and Democracy (Reaktion Books), Short writes that he believes Trump will be “abandoned by the political leadership of the Republican Party”.

Nevertheless, in his thoughtful study of the polarisation in the United States that led to the attack on Congress, Short offers a damning account of the impulse for Trump’s alleged incitement of insurrection. “The prime motivation for Trump’s actions was to avoid being seen as a loser. He told White House Chief of Staff, Mark Meadows, ‘I don’t want people to know we’ve lost… this is embarrassing,’” writes Short. “Democracy was shaken, seven people died and 114 law enforcement officers were injured, all because Trump did not want to be seen as a failure.”

Trump also features in Deterring Armageddon: A Biography of NATO (Wildfire), Peter Apps’ hugely impressive history of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation, which marks its 75th anniversary in April. In the three-quarters of a century that NATO has been in existence, the US passed from the statesmanship of Eisenhower to the crassness of Trump. App records that when he was in the White House discussing NATO manoeuvres in Europe, Trump told a military aide: “My generals are all a bunch of f***ing p***ies.”

James Pratt and John Smith were executed on 27 November 1835, becoming the last two men to be hanged in Britain for homosexuality. In James and John: A True Story of Prejudice and Murder (Bloomsbury), MP Chris Bryant explores a shameful chapter in England’s past. In just three decades, 404 men were sentenced to death for “sodomy”. Bryant’s book is powerful and demoralising, not least in his observation that the pair’s Newgate hangings proved to be a “money spinner”, particularly for the pie-makers supplying a gawping crowd. In case you think this is all arcane, Bryant points out that the judicial murder of men for adult consensual sex still exists in countries such as Brunei, Somalia and Nigeria.

Peter Carty, who used to write book reviews for The Independent, follows a group of politicised young Hoxton-based artists in his dark, zestful satire Art (Pegasus), a debut that also explores crime and London gentrification.

Finally, a recommendation for The Fetishist (Fleet), a rescued posthumous novel by Katherine Min, who died in a hospice in 2019, the day after her 60th birthday. The Fetishist is an excoriating, challenging work, centred around a daughter avenging her mother’s death. Min’s novel is a complex and at times bitingly funny exploration of the fetishisation of Asian women by white men. Her callous protagonist Daniel is “nothing special, just one in a long, boring line of fetishists – white boys who got hard whenever a slant-eyed, slim-hipped Asian girl went by”. With The Fetishist, Min has left the world something original and highly potent.

Novels by Paul Theroux, Howard Jacobson, Roisin Maguire and Andrew McMillan are reviewed in full below, along with a history of the US and Saddam Hussein and A Year of Women’s Diaries.

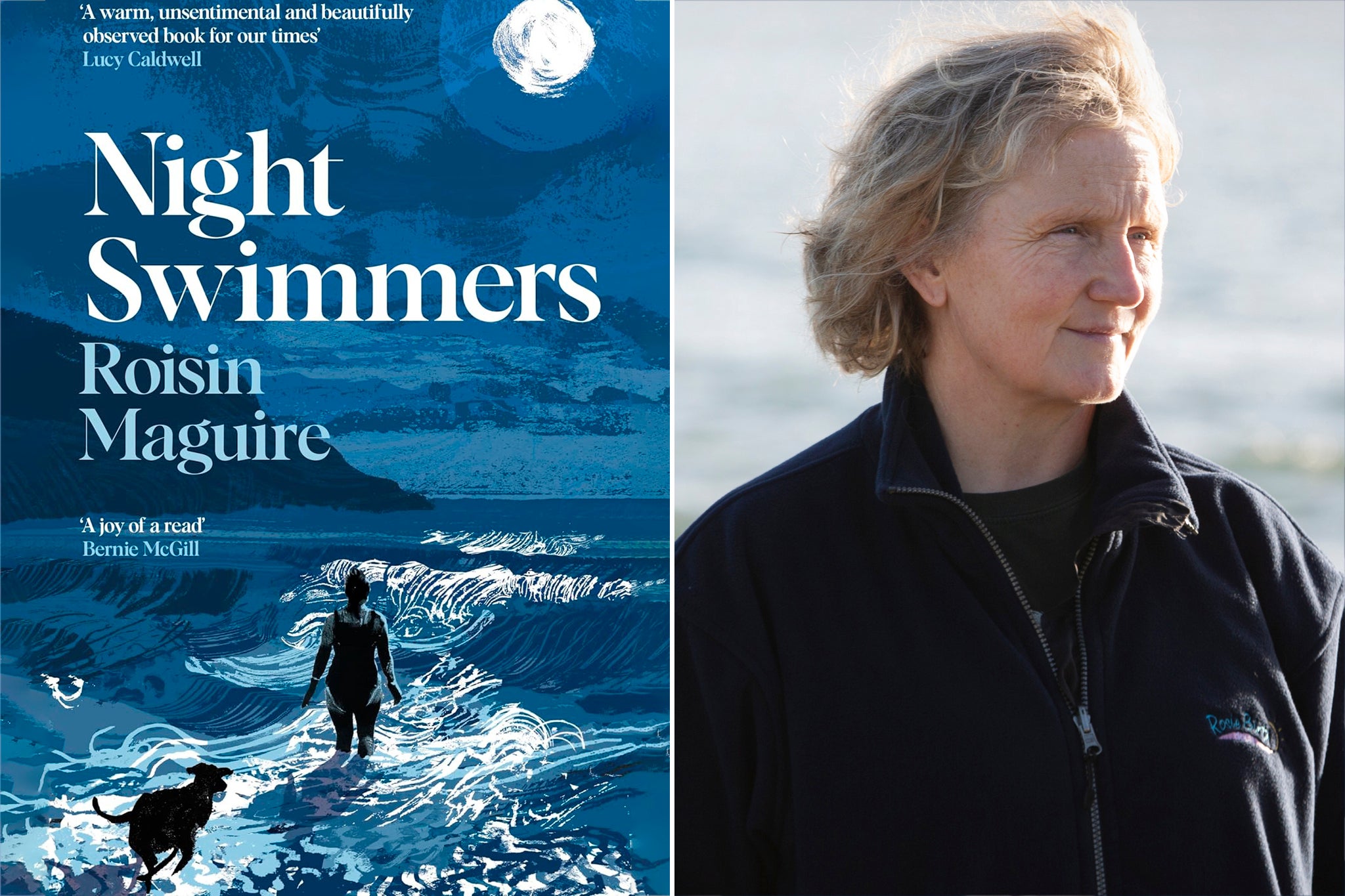

Night Swimmers by Roisin Maguire ★★★★☆

Roisin Maguire’s sparkling debut novel Night Swimmers is set in Ballybrady, a small village on the east coast of Northern Ireland, during lockdown. Evan, a “townie” seeking refuge from Belfast after the death of his baby daughter and implosion of his marriage, is at the end of his rope when his life is saved by Grace Kielty, a woman who looks “like a bag lady” and is regarded locally as “mad as a box of frogs”. Grace herself is still reeling from an old trauma and hasn’t left Ballybrady since the late Eighties.

In Night Swimmers, Maguire deftly explores mental health, loneliness, guilt, grief, and individuality. Grace, Evan – and his son Luca, a deaf eight-year-old who is as lost as anyone when he comes to stay with his troubled father – are strong characters. Around them, Maguire assembles an engaging cast that includes the pub regulars; Becky, the sharp-tongued and wise shopkeeper, and Grace’s gentle niece, Abbie.

Maguire’s enthralling story is full of wonderfully deft touches: the intimacy of two misfits gutting coalfish together, the explanation for why Becky always has the same smudge on her spectacles. She even excels in utilising text messages to add impact to a scene, a plot device that jars in less subtle hands. I loved Night Swimmers and was won over by Grace, who muses that “she hoped it wasn’t f***ing genetic, the despair”. Amen to that.

‘Night Swimmers’ by Roisin Maguire is published by Serpents Tail on 1 February 2024, £16.99

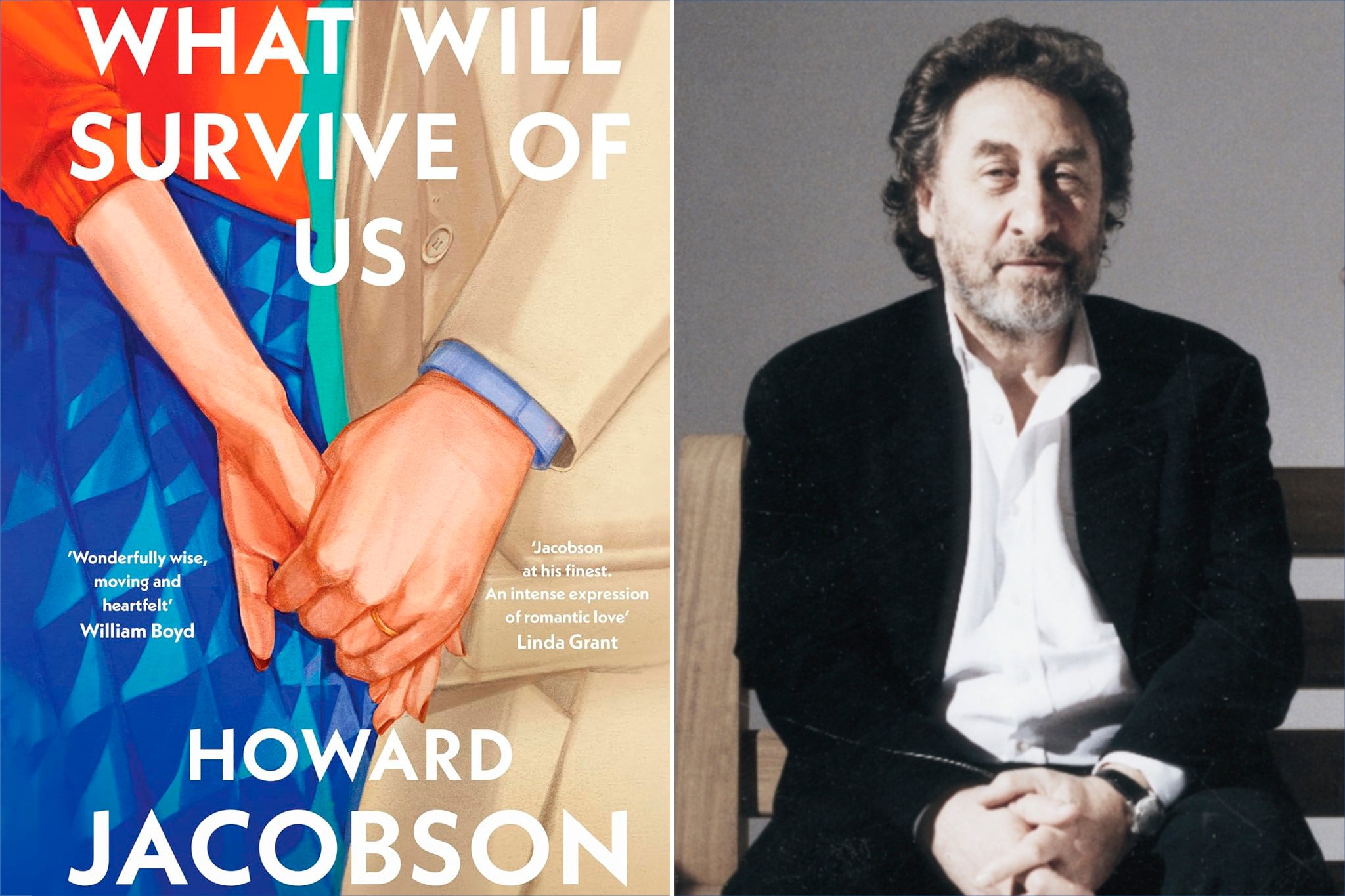

What Will Survive of Us by Howard Jacobson ★★★☆☆

Tragi-comic romantic entanglements and the damage that men and women do to one another are recurring themes in Howard Jacobson’s rich body of work. In his new novel, What Will Survive of Us, Sam Quaid, a prize-winning playwright, has a late-life affair with Lily Redfearn, an award-winning television documentary maker. This London-centric novel – Muswell Hill, Chelsea, Camden, and The Groucho Club (yawn) all feature – is divided into six parts and spans decades.

Quaid (“dishevelled trying to look like a dandy”) and Lily dissect the problems of infidelity and ageing (bigger silver pillboxes become a go-to present) as they negotiate life together in the wake of the break-ups of their respective marriages, and their reluctant decision to get hitched again. The novel is replete with the clever literary references and asides we have come to expect from Jacobson, who taught English at Wolverhampton Polytechnic. There is also a memorably confrontational scene involving Quaid and his foul-mouthed, odious old father Ossian Freud.

For part of the novel, Quaid and Lily become enthusiasts of risqué sex clubs. The idiosyncrasies of the “leather and PVC mob” provide Jacobson with the sort of comic moments (Quaid rubs down Lily’s whips with antiseptic wipes and she is caught doubting whether she really enjoys trussing up “a naked unresisting Etonian like a chicken”) that will delight the 81-year-old’s fans. I found it all a bit limp. Perhaps it’s me, but I also failed to raise a smile at quips about a gynaecologist called Dr Umlaut and a pun on vaginal atrophy.

What will survive best of Howard Jacobson is perhaps his other works, but there is still much to enjoy in this novel, especially the opening section, “Miss Picky”, in which Quaid and Lily’s courtship and the cut-and-thrust of their clever seduction is full of sparkle. As Lily muses, “talking was something they had always done well”.

‘What Will Survive of Us’ by Howard Jacobson is published by Jonathan Cape on 1 February, £18.99

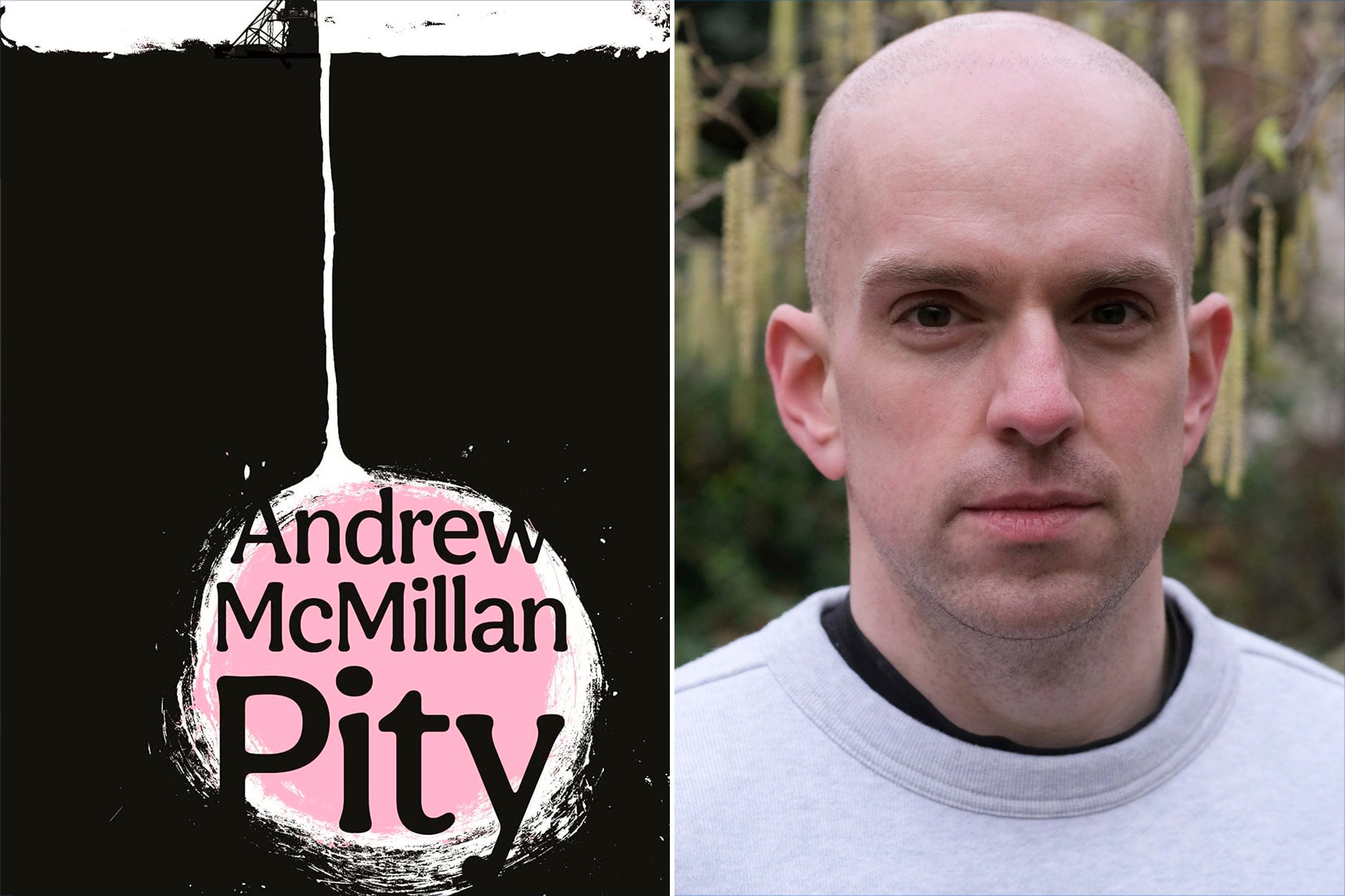

Pity by Andrew McMillan ★★★★★

“Monday, and the weekend is still unshaven stubble in his mind,” is the lovely metaphor Andrew McMillan ascribes to Brian Banks as he trudges at early dawn towards work down a dark, fearsome mine in the 1970s. He is crushed to death in this pit at the age of 51. In his debut novel, McMillan, an acclaimed poet, brings all his gifts for language to short, sharp flashbacks, which capture his narrator’s forlorn working life.

Pity is set in Barnsley across three generations of a South Yorkshire family, including Brian and his namesake son. Alex, the miner’s other son, has an only child called Simon who is trying to navigate life in modern Britain, working in a call centre, piecing together cash from a side hustle in sex work, and living for his passion: gigs as a drag artist. Broken into multiple perspectives, Pity is a fascinating look into a world forever changed by the closure of the pits – and the impact it had on marginal lives and masculinity especially.

The book shines with humour. Simon parodies Margaret Thatcher in his act – moving from “The Lady’s Not for Turning” to “This Turn is Not a Lady” – and the scene in which Simon and his father suggest possible names for his drag act, including Martha Scargill, made me laugh out loud. Through stories of Simon and his lover Ryan (his work as a security guard allows McMillan the neat trick of using CCTV surveillance as a way of filling in background events), the writer explores what it was like to grow up queer in Barnsley in a bygone era. Simon’s desire to just survive offers a parallel to the daily endurance tests his grandfather faced. The relationship between Alex and Simon is knotty, sad, and not without its own poignant twist.

I also enjoyed the sections labelled “fieldnotes”, observations from fictional academics studying Barnsley’s past; their interactions with the younger Brian are excellent. These asides offer real food for thought, prompting me to look into the true backstories of some of the Barnsley history mentioned, including the high-end fashion shop Pollyanna and the fateful Civic Hall disaster of 1908 in which 16 young children were trampled to death trying to get in to see a Saturday morning movie picture. I’m ashamed to say I knew nothing of this tragedy, but Pity makes clear that Barnsley’s past has, to an extent, been “erased, hidden, buried”.

Pity is a magnificent kaleidoscope of a novel: sad, wise, enlightening and empathetic.

‘Pity’ by Andrew McMillan is published by Canongate on 8 February, £14.99

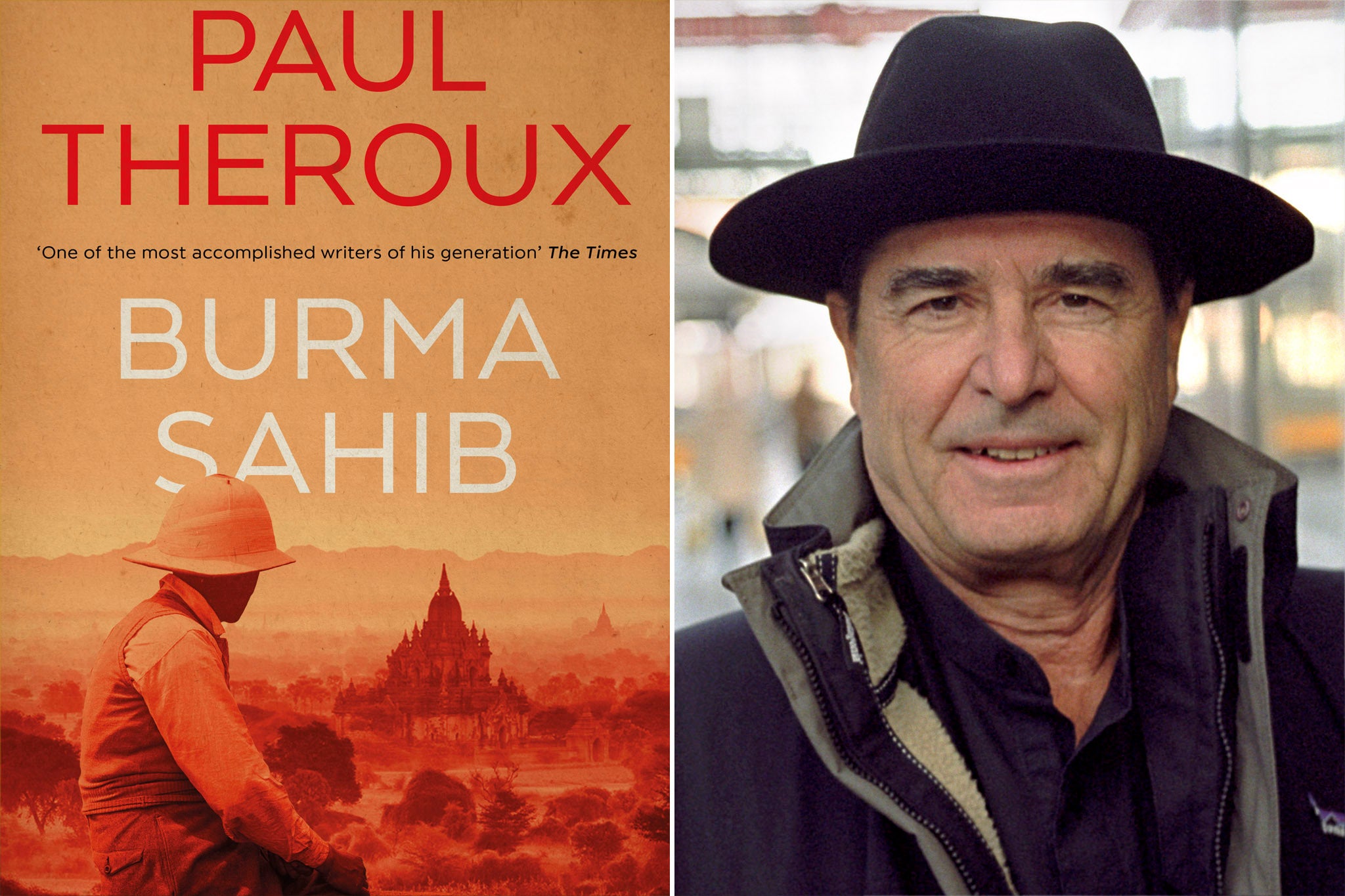

Burma Sahib by Paul Theroux ★★★☆☆

Nineteen Eighty-Four turns 75 this year and the searing hatred of authority and imperialism that are integral to that novel can, in part, be traced back to George Orwell’s experiences as a member of the Indian Imperial Police in Burma in the 1920s. Paul Theroux’s novel, Burma Sahib, a portrait of that time in Orwell’s life (then known as Eric Blair), opens with an epigraph from the author’s first novel Burmese Days: “There is a short period in everyone’s life when his character is fixed forever.”

Orwell’s maternal grandmother lived at Moulmein, and the former Eton pupil chose a posting to Burma, which was, at the time, still a province of British India; Burma Sahib is a bold, atmospheric portrait of Orwell’s life there from the age of 19 to 24. Theroux cleverly reconstructs what it must have been like to be a sensitive young loner suddenly exposed to a world of hacked corpses, raped children, and religious hatred – a world in which women could be accused of witchcraft and drowned in wells.

Massachusetts-born Theroux, an accomplished novelist and travel writer, elegantly captures Orwell’s discomfort, and ultimately revulsion, at being part of the British colonial system in its slow death throes. He came to believe that the British empire was a “colossal bluff”. Through the fictional character of a Glaswegian lout called Angus McPake, Theroux also shows the vileness of high-ranking officers who relied on the muscle of brutish lower-ranked policemen to keep the locals in check.

The young Orwell’s sex life is a prominent theme of the novel – readers are possibly left to judge for themselves his culpability for using very young sex workers in Burmese brothels – and the rancid attitudes of the representatives of the British Raj are shown in the way women are routinely referred to simply as “c***”, there solely for the pleasure of “prowling” officers.

All in all, though, I was left ultimately unsure about Burma Sahib. For all its merits as a piercing account of the despotic nature of the British Empire, and as a nuanced and sympathetic account of the young Orwell, it left me cold.

‘Burma Sahib’ by Paul Theroux is published by Hamish Hamilton on 22 February, £16.99

The Achilles Trap: Saddam Hussein, the United States and the Middle East, 1979-2003 by Steve Coll ★★★★☆

It seems George Bush and Tony Blair didn’t spend all their time together discussing whether Iraq really held WMDs. Strangely, according to Steve Coll in The Achilles Trap: Saddam Hussein, the United States and the Middle East, 1979-2003, they bonded over viewing Ben Stiller’s family-comedy Meet the Parents. Bush said Blair’s enjoyment of the movie proved he was not “stuffy”.

Although the controversial WMD saga is featured in the book, The Achilles Trap is, in the main, a study of the failed geopolitics that led to the war and Saddam Hussein’s downfall. Coll, a Pulitzer Prize winner and Dean of the Graduate School of Journalism at Columbia University, deals with Saddam’s rise to power and “furtive collaboration with the CIA”, chronicling his horrific reign of torture and murder. Among the adjectives used to describe him are “cunning, delusional, angry, inward-looking, manic, erratic and cruel”.

One bizarre thing I learnt from the book is that Saddam regarded fiction as an “instrument of propaganda”, and wrote several novels himself, including The Fortified Castle, which one scholar later called “a particularly boring and repetitive read”. It’s hard to envy any Iraqi book reviewer who had to give a star rating to Saddam’s publications.

The Achilles Trap, more than 500 pages long, is a masterful piece of modern history: well-written, judicious, and thoroughly researched. It makes sense, then, that western leaders don’t come out of it well. If you want an example of how compromised and morally bankrupt British politicians were when dealing with Saddam, Coll cites the case of 31-year-old British resident Farzad Bazoft, a freelance journalist who was hanged in 1990 for allegedly being a spy. He was “executed”, said Saddam, as “punishment for Margaret Thatcher” and her anti-Iraqi stance. Coll cites declassified British records to note foreign secretary Douglas Hurd’s advice, five days after the murder of Bazoft, advising Thatcher not to cut off trade with Iraq. “Our competitors would happily take up our share of the market,” Hurd weaselly wrote.

‘The Achilles Trap: Saddam Hussein, the United States and the Middle East, 1979-2003’ by Steve Coll is published by Allen Lane on 27 February, £35

Secret Voices: A Year of Women’s Diaries, edited by Sarah Gristwood ★★★☆☆

Books into which you wish to readily dip are always a delight and Secret Voices: A Year of Women’s Diaries, which features date-linked entries from more than a hundred diarists, is an intriguing, highly snackable guide to women’s experiences over the past four centuries.

Some diarists feature regularly – including Barbara Pym, Anne Frank, Sylvia Plath and George Eliot – but there are lots of quirky jewels to be found at random. There is humour – Lloyd George’s family all forgetting his birthday; Emma Thompson overhearing Kate Winslet and Alan Rickman bantering about the actress’s complaint that “Oh God, my knickers have gone up my arse” – alongside startling insights into the hidden worlds of power.

One revealing entry for 2 July 1956, for example, comes from political hostess Cynthia Gladwyn, whose diary candidly lifted the lid on royalty. “Tonight we had our annual dinner with the Windsors,” Gladwyn wrote. “The party was chiefly American and included Mrs Donahue, the colossally rich Woolworth woman who pays for a great deal of the Windsors’ life. She is the mother of the homosexual Donahue, for whom the Duchess conceived such a notorious passion two or three years ago, and during which she became rude, odious and strange. One had the impression that she was either drugged or drunk. She spent all her time with the effeminate young man, staying in nightclubs till dawn and sending the Duke home early. ‘Buzz off, mosquito’ – what a way to address the once King of England! Finally Donahue’s boyfriend is alleged to have told him, ‘It’s either her or me,’ and so he chucked the Duchess.”

‘Secret Voices: A Year of Women’s Diaries’, edited by Sarah Gristwood is published by Batsford on 29 February, £25.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks