Book of a lifetime: Lolita by Vladimir Nabokov

From The Independent archive: Joanna Briscoe is beguiled by the book and falls in love with the most playful, lyrically virtuoso prose writer of the 20th century – if not of all time

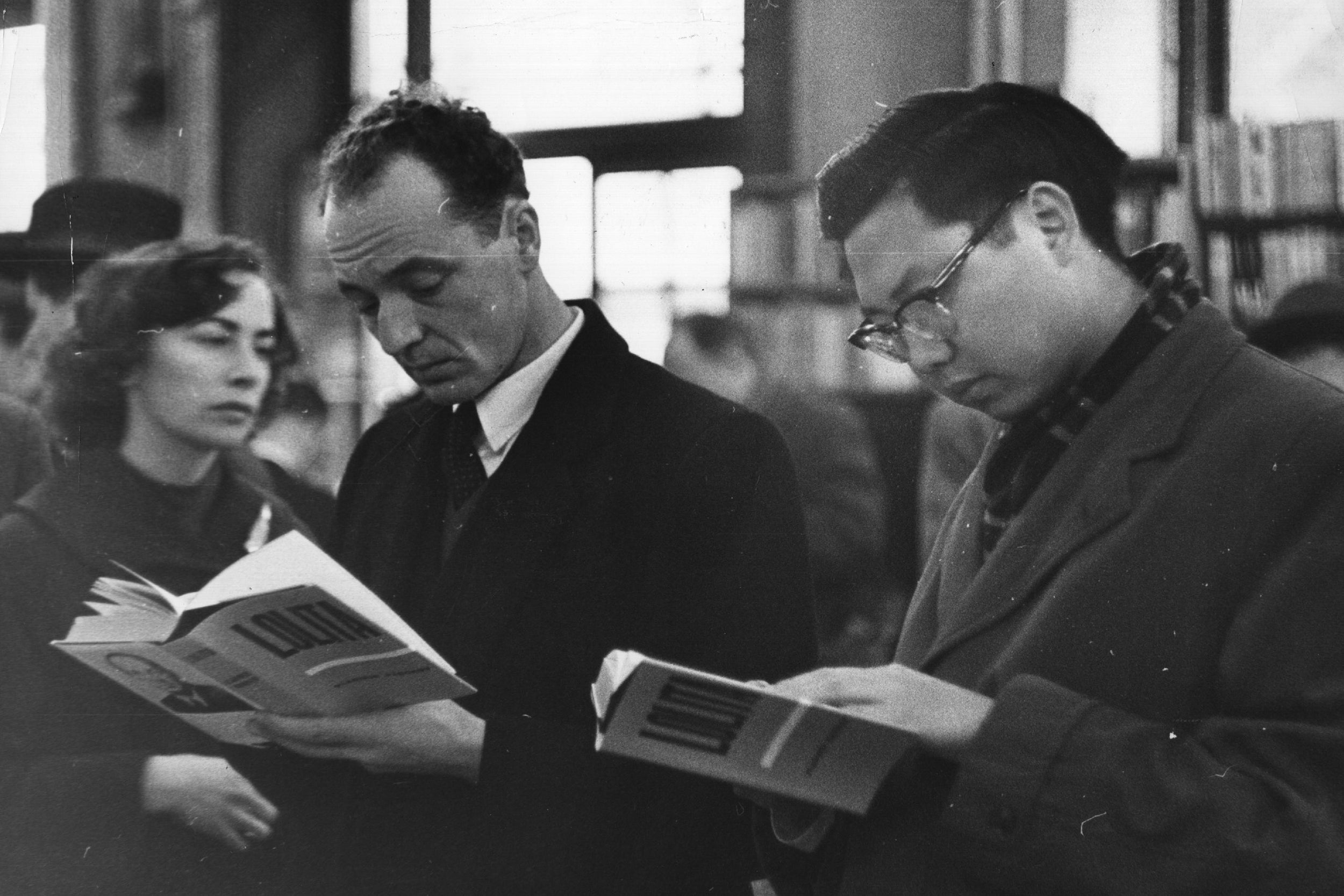

The summer after A-levels. I had promised myself that once all the cramming was over, I would buy Lolita. I felt both furtive and outrageously adult as I purchased it in The Totnes Bookshop. I nurtured hazy notions of a racy read to ease my brain after all the Chaucer, imagining this was the Valley of the Dolls with class.

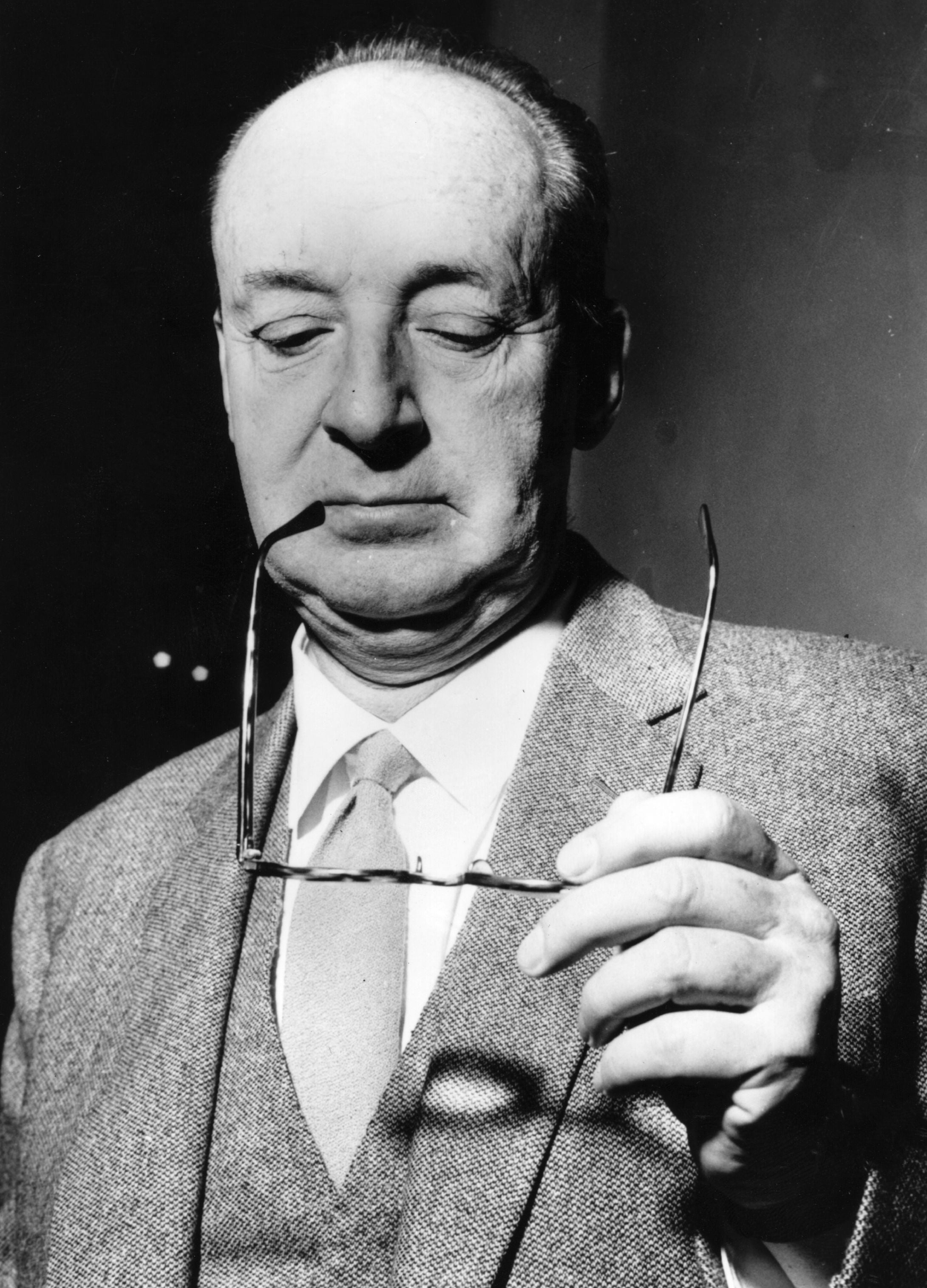

What I didn’t realise, of course, was that I was about to fall in love with the work of the most playful, lyrically virtuoso prose writer of his century – if not of all time. I started reading, and the writing inevitably blew my mind, and has never stopped astonishing me over so many re-readings. It’s like watching a tightrope walker perform Swan Lake while singing Don Giovanni while laughing at a private joke.

This is a novel so very famous; so reviled then lauded by generations of writers and critics; so filmed and misused as a concept, that ideas about it are bound to be warped. At its simplest, it’s the tale of an academic, Humbert Humbert, who is attracted to what he terms “nymphets” – certain underaged girls. One summer, he chances upon the ultimate nymphet, Dolores Haze, whom he refers to as Lolita. After a strategic marriage to her mother, he spends the rest of the novel chasing the elusive girl, while attempting to thwart a rival.

But the plot is subsidiary to a novel that works on so many levels, that is so exuberant yet controlled, witty, allusive, and breathtakingly beautifully written. Published in 1955, it is many things: a love story; by its own admission a disturbing tale of child abuse; an elaborate game of language, rhythm and subtext, and much more. What never ceases to amaze me is the fact that English was not even this Russian writer’s first language, yet his fluency and poetic agility outclass almost any native author you care to name.

What stays in the mind are throwaway descriptions: Humbert’s “salad of racial genes” and his “princedom by the sea”; the list of the names in Lolita’s class – “a poem, forsooth!”, and the “luminous globules of gonadal glow” of the jukebox. Was there ever more economy than in his recounting of his own mother’s death: “(picnic, lightning)”?

When my publishers described my novel as “Lolita meets Wuthering Heights”, I was taken aback. Did my influences show that much? But in writing of a 17-year-old schoolgirl and her relationship with her older teacher, the themes of longing and obsession and the power difference created by age come into play. In thinking back to the age I was when I first read Nabokov, perhaps I had absorbed more of its themes than I had thought.

One of my most treasured possessions is a rebound first edition of Lolita. It’s a novel that never goes away.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments