Ben Nicholson at Pallant House review: Artist’s story illuminates the struggle of British culture to revitalise itself

The show effectively draws you into Nicholson’s world, highlighting the influence of still life on even his most apparently abstract work, with many of the original objects displayed beside the paintings they inspired, writes Mark Hudson

These days, the Father of British Modern Art is best known as Mr Barbara Hepworth. For decades, Ben Nicholson appeared to be almost the only credible British modernist, who kept the flag flying for abstract art in the dark days of the Thirties. He squared up to international giants of the order of Mondrian and Walter Gropius as part of the interwar Hampstead scene, and later as kingpin of St Ives modernism. Meanwhile his wife, collaborator and later rival, Hepworth, appeared too tied to the human figure and to landscape to be fully “modern”, and was, as a woman, an inevitably anomalous figure.

Over the decades since, of course, Hepworth’s status has kept on rising – it seems only a matter of time before she’s hailed as the greatest British artist of the 20th century – while Nicholson now appears just one of many slightly neglected “modern British” artists.

Indeed, where Hepworth is currently riding high with an acclaimed new biography and accompanying exhibition at Hepworth Wakefield, Nicholson is making do with a show focusing on his still lifes. And while there’s no disgrace in a show at Chichester’s excellent Pallant House, the exhibition does – probably unintentionally – underline the current gap in status between the artists by having a whacking great wooden sculpture by Hepworth towering over the entrance.

Once inside, however, the show effectively draws you into Nicholson’s world, highlighting the influence of still life on even his most apparently abstract work, with many of the original objects displayed beside the paintings they inspired.

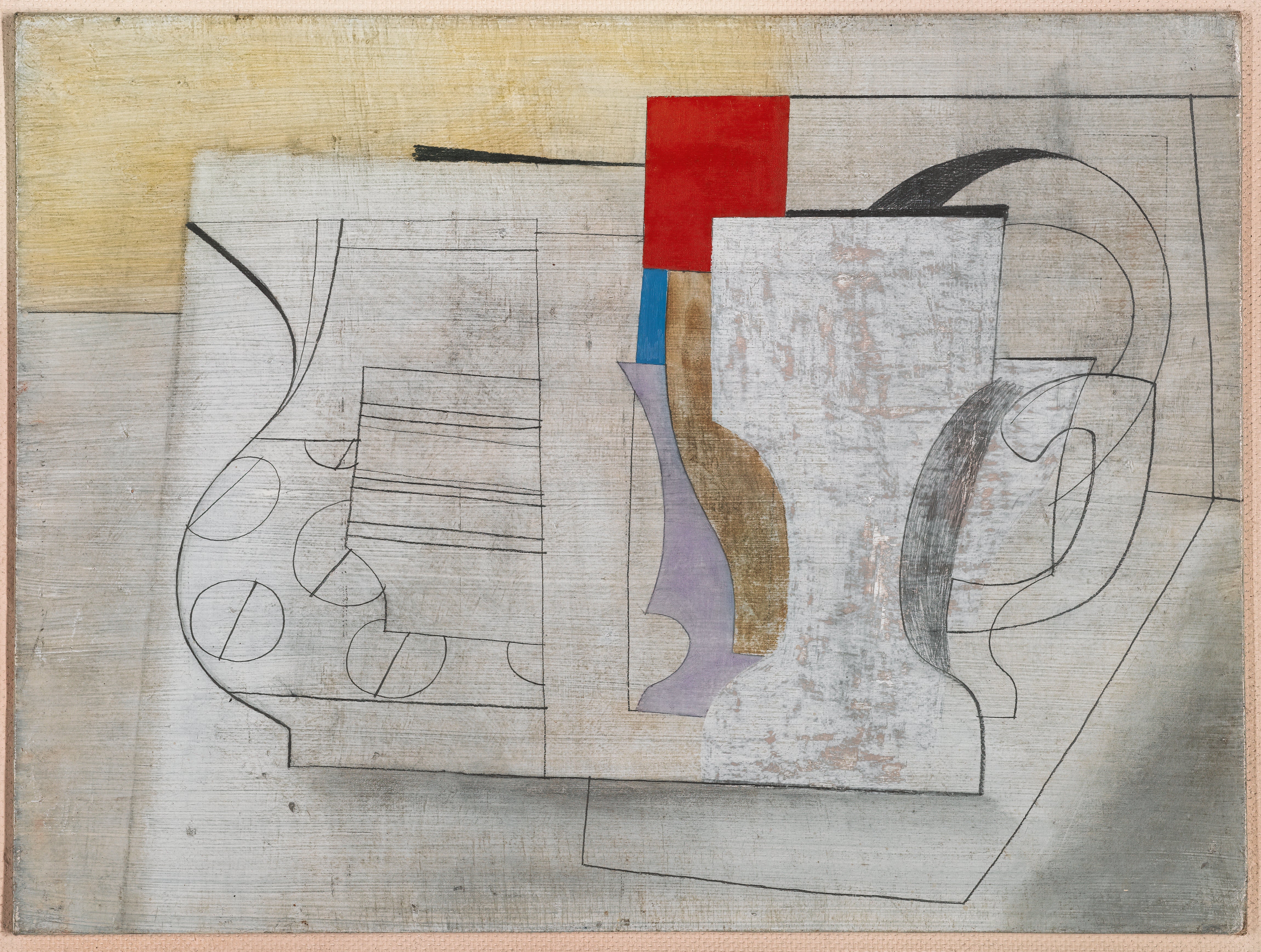

Overpowered by his famous father, the Victorian academic painter William Nicholson, he comes across as a faintly dilettantish figure who progressed through creatively fruitful (but competitive) relationships with powerful women artists. His first wife, the painter Winifred Roberts, had an essential role in his immersion in European modernism and in building an appreciation of brilliant colour. Nicholson’s own instinct, however, was for tastefully earthy browns and ochres, evident in 1925 (Still Life with Jug, Mugs, Cup and Goblet), with its seductive textural contrasts between roughly applied washes and elegantly incisive pencil lines. An aspiring cubist, he was drawn more to Braque’s subtle refinement of form than Picasso’s anarchic visual gamesmanship.

With a new understanding of the painting as a quasi-sculptural object, rather than just a picture of something, and inspired by his second wife, Hepworth, Nicholson began scraping the paint from his canvases with a razor blade to create an artfully distressed look, and gouging into wet paint with the head of his brush.

Yet put into faux-naïve still lifes, with playing-card images and random text from bottles a la Picasso, these techniques feel ultimately decorative. A large painting of a criss-crossed guitar and violin, their outlines overlaying each other in quasi-cubist fashion, feels very Braque-lite, with its elegantly sombre browns. The forms are slightly flaccid, with none of the rhythmic tension required for an image of musical instruments.

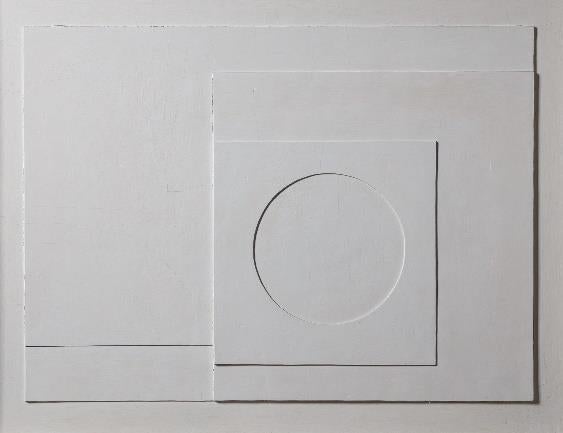

Yet following a visit to Mondrian’s Paris studio in 1934, there’s a sudden incursion of just the kind of less-is-more severity you’d hope for from the First British Modernist. Comprising just four layered sheets of white-painted hardboard with a circle cut into the top, 1936 (relief) has a perfect, serene balance that mystified most contemporary commentators, but which Nicholson’s fellow painter Paul Nash proclaimed as “the discovery of a new world”.

This feels much more like it. And the display of white china bottle and goblet in the adjacent cabinet convinces that the work is a kind of hyper-abstracted still life.

While it’s a shame that only one work from this series (arguably the best things Nicholson produced) is included, the serial composition 1940-42 (two forms) feels in tune with the most exacting expectations of European modernism – one of nine canvases in which the same rectangular elements were redeployed in various colour combinations. Yet still-life elements soon reappear: the handle of an old English mug here, the curve of a goblet there. The inclusion of an abstracted union flag in 1945 (Carbis Bay) reminds us that the Second World War has ended. While it’s reassuring that Nicholson – with his rarefied visual preoccupations – was at least aware of real-life events, the quirky arrangement of abstracted St Ives townscape and yet more mugs carries the image close to the whimsy of retro-leaning illustrators of the time, such as Edward Bawden and Eric Ravilious. It’s just the kind of parochial Englishness that Nicholson is thought to have transcended.

In the last room, covering the period of his greatest fame, from the early Fifties to his death in 1982, he synthesises the elements from the earlier work, with planes of pure colour and fetchingly worn surfaces held in tension with those characteristically elegant pencil lines – and with constant visual nods towards the same few domestic objects. If these works are never less than interesting – always a slightly damning word in this sort of context – there’s a fatal tastefulness; touches of mint green and muted turquoise bring a slight flavour of a John Lewis furnishing department. The sense of urgent decisiveness necessary to great art is most evident right at the end, in tiny etchings from 1967, in which Nicholson’s seductive lines are pared to a crucial, minimal essence.

Nicholson may in the greater scheme of things have been a relatively minor artist, but he is a major British cultural figure. His story illuminates the struggle of British culture to revitalise itself in response to the massive upheavals of the 20th century – a struggle that points straight through to where we are now. This beautifully mounted exhibition takes us enjoyably, at times poignantly, to his world. If the emphasis on still life highlights some of his slightest works, the sheer mundanity of most of the real objects we’re shown pinpoints one of his strengths: the ability to extract vital form and perceive the universal in everyday utensils that were, in every other respect, utterly unremarkable.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments