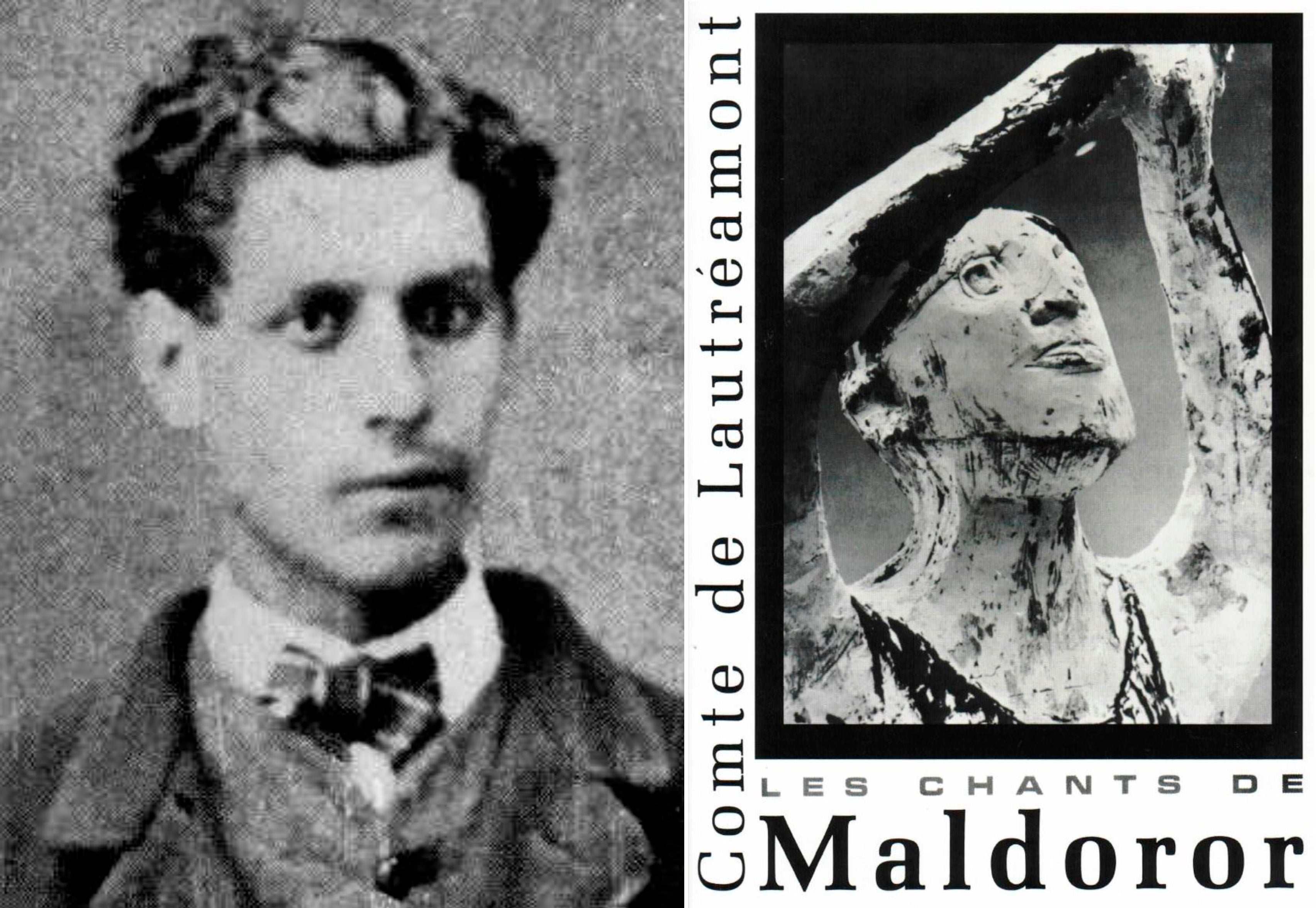

Book of a Lifetime: Les Chants de Maldoror by the Comte de Lautréamont

Richard Milward plunges into the forbidden realms of ‘Les Chants de Maldoror’ by the Comte de Lautréamont

I’m absolutely mad on mad people. Some of my favourite artworks and novels appear to have been spewed from the hands and minds of mad folk, from Henry Darger to Alfred Jarry to Jean-Michel Basquiat, but none has made a more prominent dent on my brain than the Comte de Lautreamont’s potty page-turner, Les Chants de Maldoror. It’s like an old, twisted rulebook on how to break all literary rules.

It was only a handful of springtimes ago I discovered the book, daydreaming through my Surrealism lectures at the barmy Byam Shaw School of Art off Holloway Road. I’m sure André Breton would have approved. I was probably dreaming of lobsters or eyeballs getting sliced by razor blades, when we were given this hand-out with a quote from Maldoror: “He was… as beautiful as the chance encounter between a sewing machine and an umbrella on the dissecting table!” Just like that, I’d found a literary soulmate.

You don’t have to be mad to read Maldoror, but it helps. First published between 1898 and 1869 – and devoured by the Surrealists – it is perhaps the most kaleidoscopic, stomach-churning piece of literature you’ll ever come across, where sleepy hermaphrodites rub shoulders with randy octopuses and lice “as big as elephants”. When Maldoror, the sadistic protagonist and master of disguises, isn’t giving himself a Chelsea Smile, he’s torturing people or having sex with a female shark (the only living creature with anything in common with him – a violent temperament).

Whenever I feel inclined to reach for a crap literary cliché, I feel ‘Maldoror’ breathing heavily on the back of my neck

What I love most is the way, back in the 1860s, Lautreamont wasn’t afraid to unleash his deepest secret fantasies, however murky and disgraceful the realms of his mind might seem. Today, it irritates me how a lot of writers avoid getting their teeth into sex scenes or violence but gleefully describe a lovely walk in the park for five or so pages.

Maldoror’s teeth chomp on many poor young boys’ flesh in the book’s six cantos, but his tongue remains firmly in his cheek. By the end, it’s clear Maldoror’s disregard for humankind is a metaphor for Lautreamont’s disregard for the traditional novel. Phrases such as “handsome as the retractibility of claws in birds of prey” straddle madness and genius in such a way it makes me blush with reverence.

Whenever I feel inclined to reach for a crap literary cliché, I feel Maldoror breathing heavily on the back of my neck. While Lautreamont’s filthy, rotten banquet may not be to everyone’s taste, ultimately his writing aims to invigorate our dulled, softened literary appetites. In the introduction, the author gives a “warning to readers” that “the deadly emanations of this book will dissolve [your] soul as water does sugar”. Those of you in the mood for a riotous orgy of cruelty and mayhem won’t be disappointed. Lautreamont is the master of subversion. But young boys and female sharks, beware.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks