No plastic? Fantastic! Meet the brothers who are using robotics to produce plastic-free recycled clothes

Lizzie Rivera visits a factory on the Isle of Wight and finds a firm taking sustainability to a new level

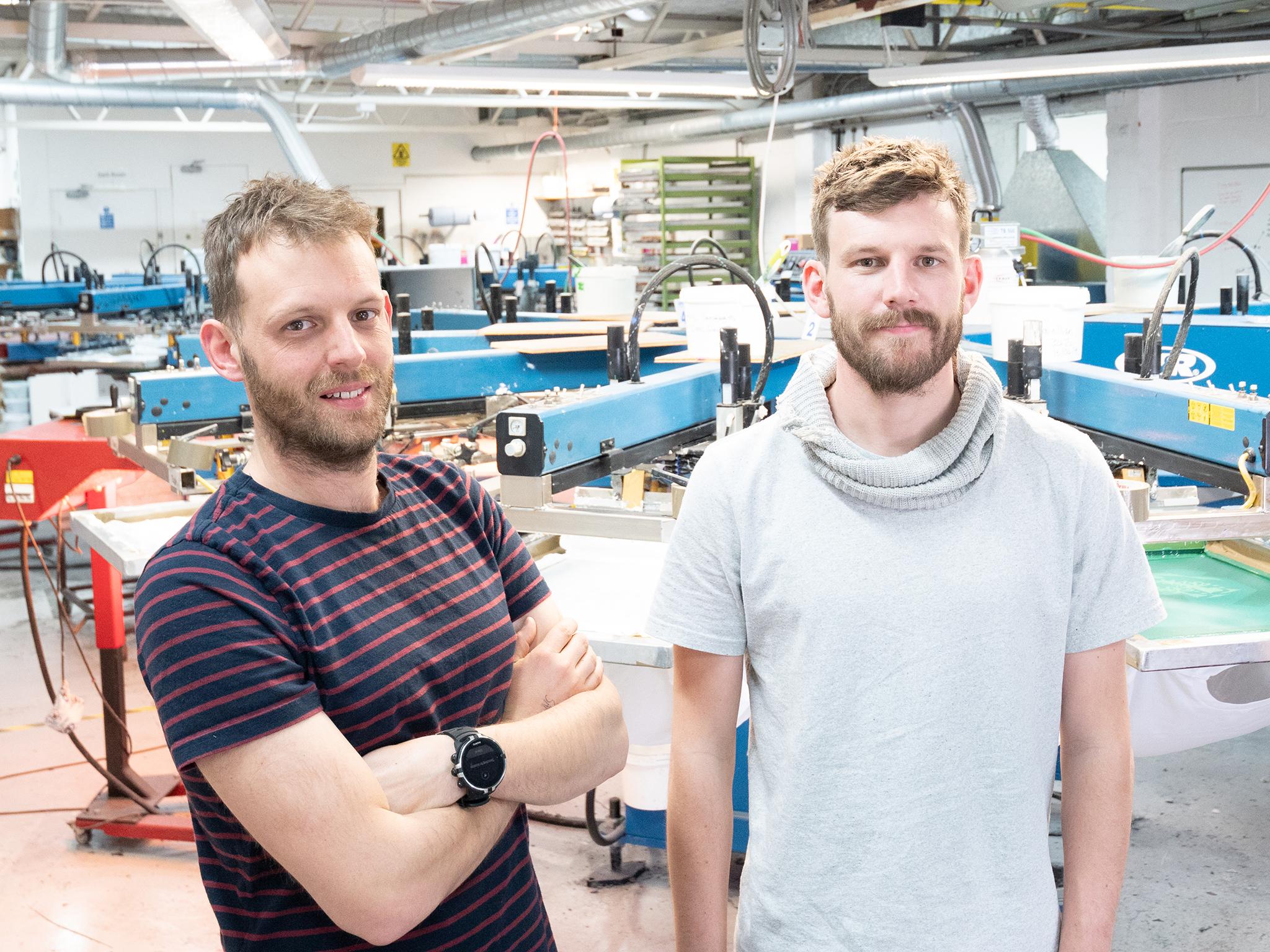

How do you introduce the brand that has cracked the supposedly elusive circular economy? You begin in the same way they design their clothes – at the end. But in true circular economy fashion, the end is just the beginning of the story... “I know, we’ll write your first piece of code, that will be fun,” says Mart Drake-Knight, the 32-year-old co-founder of the fashion tech company that is set to transform the industry as we know it. I’ve been well and truly “Marted”, as one of his employees describes it later.

A tour of the Teemill factory on the Isle of Wight usually takes around half an hour; by the time we’re coding at the boardroom table, handmade from salvaged materials, we’re already an hour-and-a-half late for lunch and I’m just learning that every programmer’s first line of code starts with those two little words: “hello world”.

But first, we have to get one thing straight, says Mart: “Technology on its own solves nothing. It’s kind of like a chainsaw – in the hands of a lumberjack, it’s life-changing for a person and their family. In the hands of a psychopath, it’s devastating for everyone. The key is the conscientious application of technology.”

For 10 years, Mart and his brother Rob, 33, have been creating solutions to our fast-fashion problems, right under our noses. Their factory is powered by renewable energy, they use non-toxic inks, 97 per cent of the water used to dye the products is recovered and they have practically eradicated single-use plastic from their supply chain.

Technology on its own solves nothing. It’s like a chainsaw – in the hands of a lumberjack, it’s life-changing for a person and their family. In the hands of a psychopath, it’s devastating for everyone

They launched their first company, fashion brand Rapanui, in 2010 from their garden shed. In 2014 the brothers set up sister-company Teemill to enable charities, initially, to use their technology for free to build e-commerce stores and print their designs to order, in real-time. This made Teemill’s 100 per cent organic cotton products more widely available, while removing the need for charities to have to invest in bulk orders or deal with surplus stock when creating merchandise.

Fashionistas Kate Moss and Vivienne Westwood have been photographed wearing their tops; comedian Ricky Gervais posted their “End Trophy Hunting Now” slogan tee on Instagram; adventurer Ranulph Fiennes took one of their hoodies to Antarctica.

They have partnerships with the likes of designer Katharine Hamnett, charities such as Save The Children and WWF, and ethical companies like Lush cosmetics. Yet, despite an estimated 1 million products being in circulation at any one time, both brands still relatively fly under the radar. You possibly own one of their T-shirts, but you’ll have no idea it was produced by them.

Perhaps it’s because the ferry across the Solent is a journey too far to be practical, and not quite far enough to be exotic: though the coastal route to Freshwater is a beautiful one. Possibly it’s because they mainly sell T-shirts, which aren’t sexy enough to make headlines. Maybe it’s that sustainability hasn’t really been a hot topic, excuse the pun, until fairly recently.

Conceivably, it’s because their achievements make a mockery of multibillion-pound fashion brands signing G7 fashion pacts and working towards 2030 sustainability goals. They are the antithesis of fast fashion and yet can deliver you a £19 T-shirt with a bespoke design within 24-hours of you ordering it. At peak performance, they are producing a T-shirt every second and their business is doubling in size every year. “Sustainability cannot be a luxury. It has to be for everyone,” insists Mart.

Just this year the brothers cracked – truly cracked – the circular economy. Importantly, the process doesn’t involve plastic.

When looking at the whole product life cycle, we realised that there’s no such thing as waste, it’s just a resource going to waste

In the race to the bottom for faster and cheaper fashion, low-quality material is often blended with polyester, which creates items of clothing that are hard to remake back into anything of value. But by using higher quality organic cotton from the start, and coming up with some clever engineering solutions inside the factories that respin recovered fibre, Teemill has built a supply chain where their T-shirts can be sent back and remade into new T-shirts. Like the energy that powers their factory, the process is renewable – older and newer material streams are mixed together so T-shirts can be remade time and time again.

“When looking at the whole product life cycle, we realised that there’s no such thing as waste, it’s just a resource going to waste,” says Mart. “Utilising it is common sense, and that happens to be great for the environment and good for business because we keep the value in the system.” Even the unusable fibres are mixed with water and used to make paper notebooks, stickers and packaging, printed with soy sauce.

They have been working towards this goal since their inception, always conscious of the materials they are using, not just for the garments, but for the labels and dyes as well. Every product is designed to send back for remanufacturing, with customers incentivised by free postage and a £5 credit to go towards their next purchase.

“I think the most interesting part of our business is the fact that everything we’ve ever made, we designed with the end of life in mind,” says Mart.

“Regardless of how long you have a garment, most fashion systems design clothes to be thrown away at the end of their life and that currently leads to a truckload of textile waste, burned or buried in landfill every second. If everyone halves their waste that’s a good start. It means a dump truck full of waste getting burned or buried in landfill every two seconds.

“But that’s not a solution. If you’re in a car driving towards a cliff with your friends, slowing down doesn’t change the end result – you’re still going off the cliff.”

30,000

products made with waste material so far

Currently, a ton of material is being recycled each month, with 30,000 products made with waste material so far. Their T-shirts are like a baker’s starter dough, they could be one year old or 10 years old.

They aim to recycle everything ever bought from them – the challenge is their products are built to last so this could take some time. Mart explains: “It doesn’t matter how many times the system goes round. You could say, let’s buy fewer items and it goes round slower. Or you might say, I want to buy more, so it goes around faster. The system goes round, not along.”

100bn

items of clothing bought each year

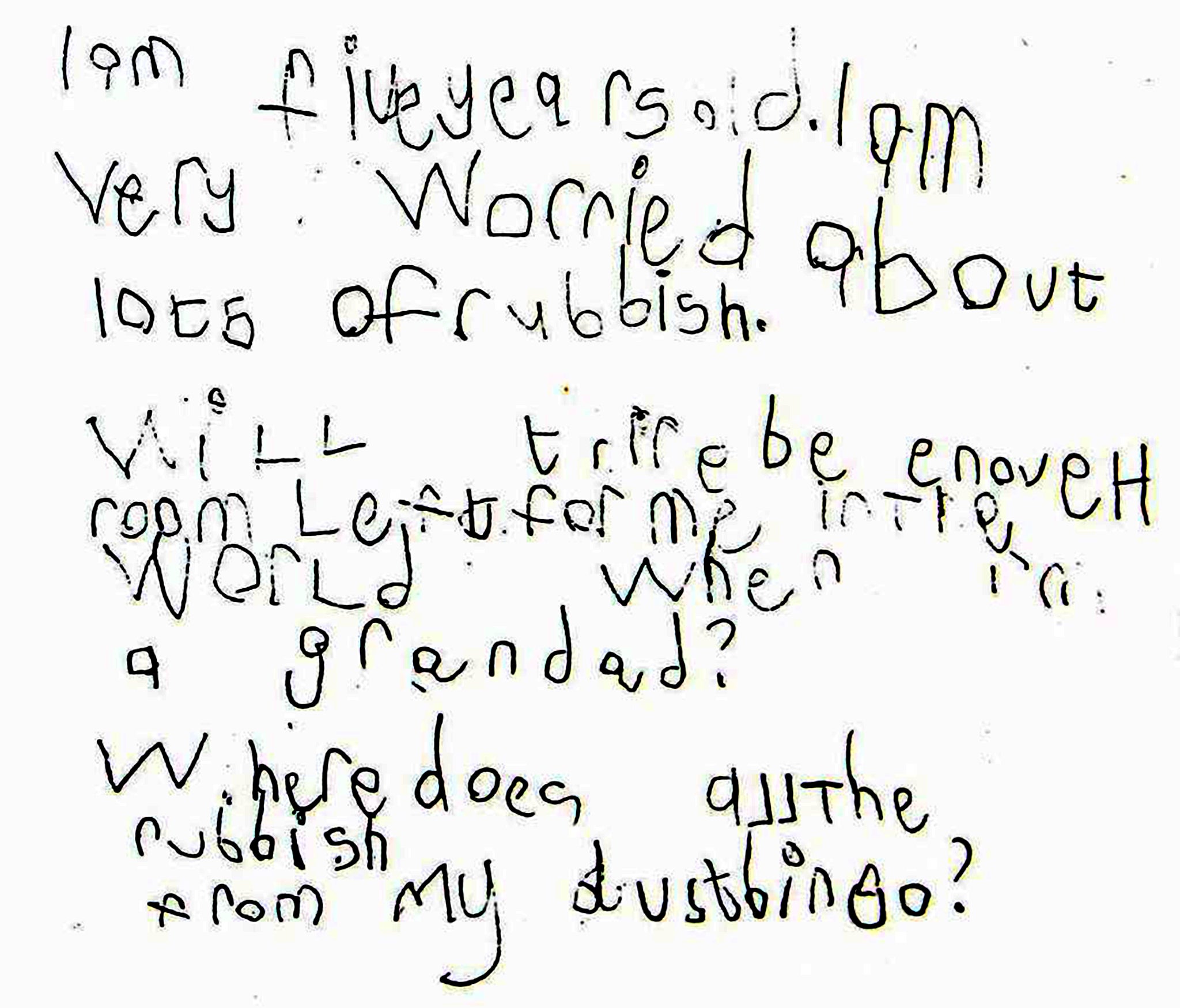

Rapanui’s whole reason for being is to eradicate waste from the fashion industry. The story starts when Mart was just five years old walking to school, hand-in-hand with his mum. He innocently asked about where rubbish from the bin ends up and was so traumatised by her answer (landfill) that she had to take him home. He shows me the letter they wrote to the binman together, which reads: “I am five years old. I am very worried about lots of rubbish. Will there be enough room left for me in the world when I’m a grandad? Where does all the rubbish from my dustbin go?”

Today, a staggering 100 billion items of clothing are bought each year, and three out of five T-shirts will end in landfill within 12 months.

We’re trying to do to fashion what Elon Musk did to the car industry with Tesla

The brothers didn’t go into fashion because they have a particular eye for design and love of style, they saw a “dirty” industry they wanted to disrupt. “We’re trying to do to fashion what Elon Musk did to the car industry with Tesla,” Mart says.

Broadly speaking, Mart, who studied engineering at university, looks after the tech, while Rob studied business and handles that side of things. Their garments are the canvas for both established or aspiring designers to work. Just over two years ago, they opened their e-commerce platform to anyone and now 97 per cent of the 40,000 people using it are start-up brands, with profits split 50:50 between Teemill and store owners.

This technology has designed waste – and waste-inducing economies of scale – out of the making process by digitally printing designs one at a time to order, using a reconditioned classic Epson inkjet printer similar to the one you probably had at home a few years ago. “Why are we waiting for big brands to turn around and say they had a change of heart and are going to be values-based organisations now?” asks Mart. “We’re providing the tools for people to build their own ready-made values brand instead. It’s disruption, pure and simple.”

Mart is passionate that solving sustainability is also a social issue. Theirs is a classic entrepreneurs tale that began with £200 savings each, £70 of which they blew on letterheads and business cards. At the time, both Mart and Rob were struggling to find jobs locally. Youth unemployment is a big issue on the Isle of Wight, almost nine per cent of the current resident population aged 18-24 are claiming out of work benefits. Most leave to pursue higher education, employment and career opportunities on the UK mainland and beyond.

At Teemill, the average age of their 65 employees is 25 years old. All have access to an employee-ownership scheme and a clear path for progression. With the help of a dedicated mentor, the most motivated employee can follow a transparent digitised programme to go from complete newbie to a leadership role within 18 months.

Their robotics engineer, Adam Bullen, was a seasonal farmworker with no qualifications or experience to suggest that should be his path when he joined as an apprentice, five years ago. But he had passion and motivation and a willing teacher in Mart. It’s another Alan Sugar cliche, and one that Mart is very aware is the exception, not the rule. Employee self-confidence is usually one of the first things they have to build up.

Everyone, from the people packing, folding and sorting clothes to coders, is encouraged to come up with ideas for improvements with whiteboards around the factory on which to write their ideas. These are then discussed every Friday, with the best ideas implemented by the team, then and there if possible. Their motto is “our favourite time is now”.

“These innovations are possible because automation frees up people’s time and capacity to do this sort of thing,” says business development manager James Gray. “There are no wrong ideas, which sounds naff, but it isn’t.”

One comment said that carrying socks and underwear from A to B across the factory was literally a pants idea – time-consuming and non-value-adding. So the manufacturing team are custom printing 3D parts to create a new robot out of an old vending machine. “We’re automating away the jobs that are an insult to humanity. We shouldn’t expect young people to do the rubbish jobs we had to do, they should have better jobs where they can provide more value,” explains Mart.

The brothers have built the machine that, in the right hands, can transform the clothing industry

Teemill reinvests the profits these efficiencies generate – the picking and packing robot directly pays for the eco-friendly paper packaging, for example, which is at least five times more costly than plastic. There are no rush jobs or zero-hour contracts at the printing factory because they have built a bespoke AI scheduler that accurately predicts orders, how fast each person works and creates the shift schedules in real-time – giving each worker two weeks’ notice.

This means there’s no need for middle management, either. Workers know whether they’re on track or not by a simple green or red light system and can manage themselves and any issues, accordingly. This allows them to get on with the job energised by the dulcet tones of Justin Bieber – or techno tunes, depending on who’s controlling the playlist – blaring at full volume on the production line. With the circular economy T-shirts now in production, the final piece of the sustainable puzzle is in place.

The brothers have built the machine that, in the right hands, can transform the clothing industry. It’s a blueprint for a factory that can be replicated anywhere in the world. “That’s what this piece of paper is over there,” says Mart, nodding to some plans, for now top-secret, casually folded over at the end of the table.

Goodbye waste. Goodbye plastic. Hello world.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments