Robert Paul: The showman and pioneer who was written out of cinematic history

Armed with a filming device of his own invention, the dynamic Victorian captured a world very alien to our own. David Barnett explores the figure who helped define the big screen we know today

There is a lot of debate about who was the true inventor of cinema. Was it the Lumière brothers? Louis Le Prince? Georges Méliès? Thomas Edison? William Friese-Greene? Historians and students of film have their own favourites for the title, and it’s true that all of them, to some extent, played their part in the dawn of the moving picture.

But what about the actual cinema industry itself? While those names above have gone down in history for their parts played in developing the technology that eventually led to the rise of one of the biggest industries on the planet, the credit for getting bums on seats to actually watch the films should go to a more unknown, yet no less important figure in cinema history: Robert Paul.

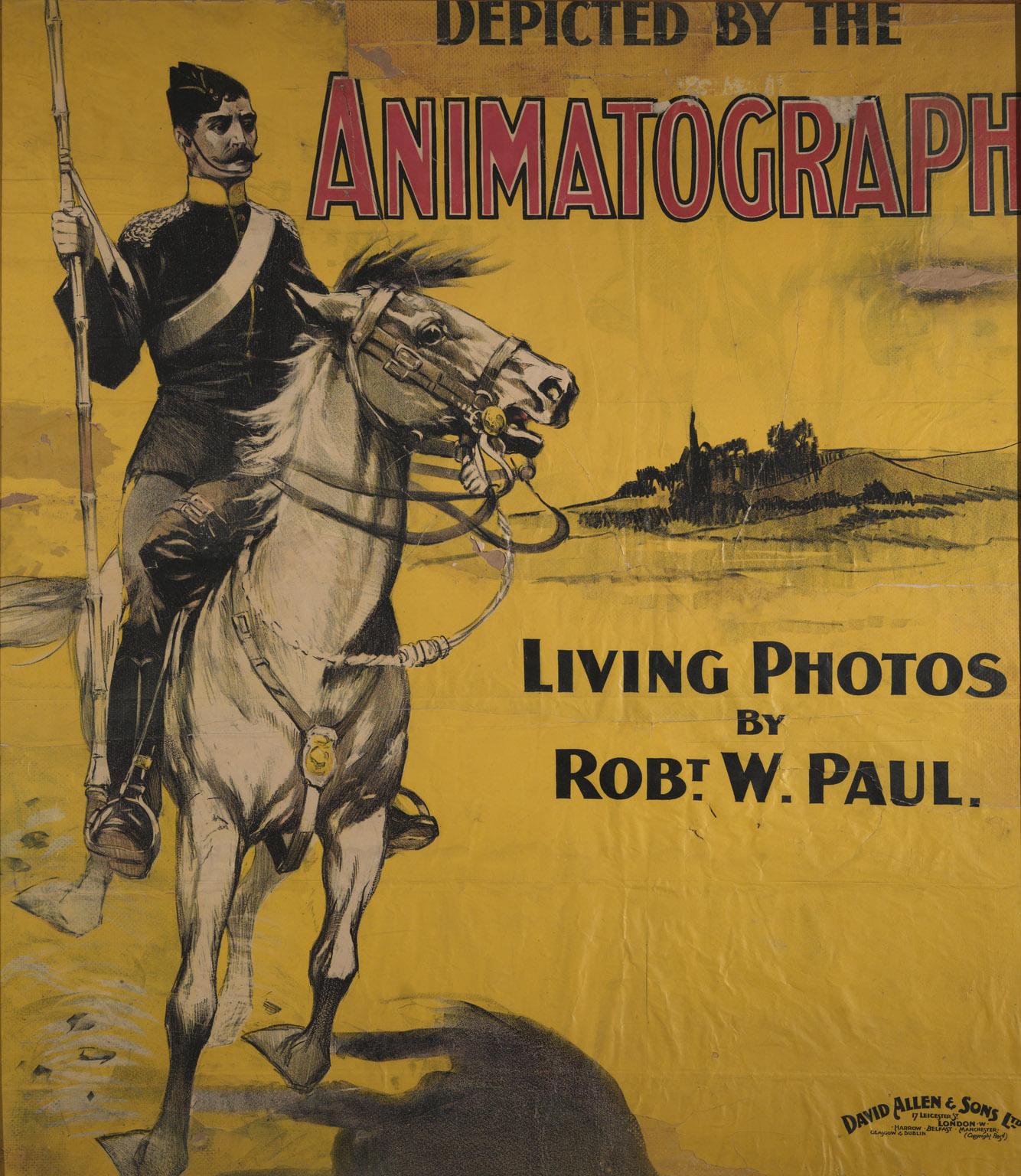

This year marks the 150th anniversary of the birth of Paul, who went on to build the first commercially successful film projection equipment in the 1890s and set in motion the industry that would get the films from the studios of the auteurs and into the sightline of the viewing public.

Although largely forgotten these days, Paul was an entrepreneur, a pioneer and a showman of almost PT Barnum-esque proportions, with ideas that not merely led to the formation of industry but other, unrealised schemes including, astoundingly, a forerunner of what we today know as the immersive 4D cinema experience.

Which is why a new exhibition devoted to Paul and beginning today (22 November) at the National Science and Media Museum in Bradford, West Yorkshire, has the title The Forgotten Showman: How Robert Paul Invented British Cinema.

Toni Booth, curator of film, says: “We are thrilled to be highlighting the important contribution of Robert Paul to the British film industry.

He was the principal figure during the British film industry’s first decade – he produced over 800 films, made the first commercially successful projector, built his own film studio and devised trick effects

“Paul’s story has remained relatively hidden from the public yet his contribution to cinema as we know it is hard to rival. Britain had been at the forefront of a number of new technologies in the 19th century, not least in photography and film, but Paul was able to take innovations in film to the next level and to a global audience.

“We want to celebrate the beginning of the British cinema industry, and Robert Paul is the perfect person through which to do this. He was the principal figure during the British film industry’s first decade – he produced over 800 films, made the first commercially successful projector, built his own film studio and devised trick effects.

“But he remains largely unknown to the British public. He should be thought of in the same way the Lumière brothers are to French cinema and Thomas Edison is in the US.”

Robert Paul was born on 3 October 1869 at 3 Albion Place, off Liverpool Road, Highbury, north London. He studied at the City and Guilds Technical College in Finsbury and started his career working in the electrical instrument shop of the Elliot Brothers company on The Strand.

In 1891 he began his first business, working out of Hatton Garden and producing instruments to meet the growing demand in the growing electrical industry.

His move into cinematography came almost by accident, when he received a commission that intrigued him beyond merely fulfilling the client brief.

Author John Barnes, who wrote the five-volume The Beginnings of the Cinema in England, explained in a piece for the victorian-cinema.net website: “Paul’s involvement with cinematography came about by chance, when he was asked to make replicas of Edison’s Kinetoscope, a peepshow device for viewing 35mm films by transmitted light, which had not been patented in England. Having agreed to manufacture the machines for his clients, Greek entrepreneurs Georgiades and Tragides, he then decided to make others for himself.”

The Kinetoscope was a forerunner of cinema but a more personal experience rather than a shared one; the movies were viewed through a peephole rather than projected on a screen.

Paul perfected the technology, but there was only one problem: the movie industry was as in its infancy as the equipment development, and there weren’t many films available to actually show on the device. So he decided to solve this problem as well.

Barnes writes: “The only films available were controlled by the Edison company and so in order for Paul’s Kinetoscope business to succeed, it was essential that he make his own films.

“With only the Kinetoscope machine and its films to go on, Paul, with the assistance of a professional photographer, Birt Acres, designed and manufactured a cinematograph camera, now known as the Paul-Acres Camera.

“By 29 March 1895, the first successful English film had been shot, showing Paul’s friend Henry Short outside Clovelly Cottage, Barnet, the home of Birt Acres.”

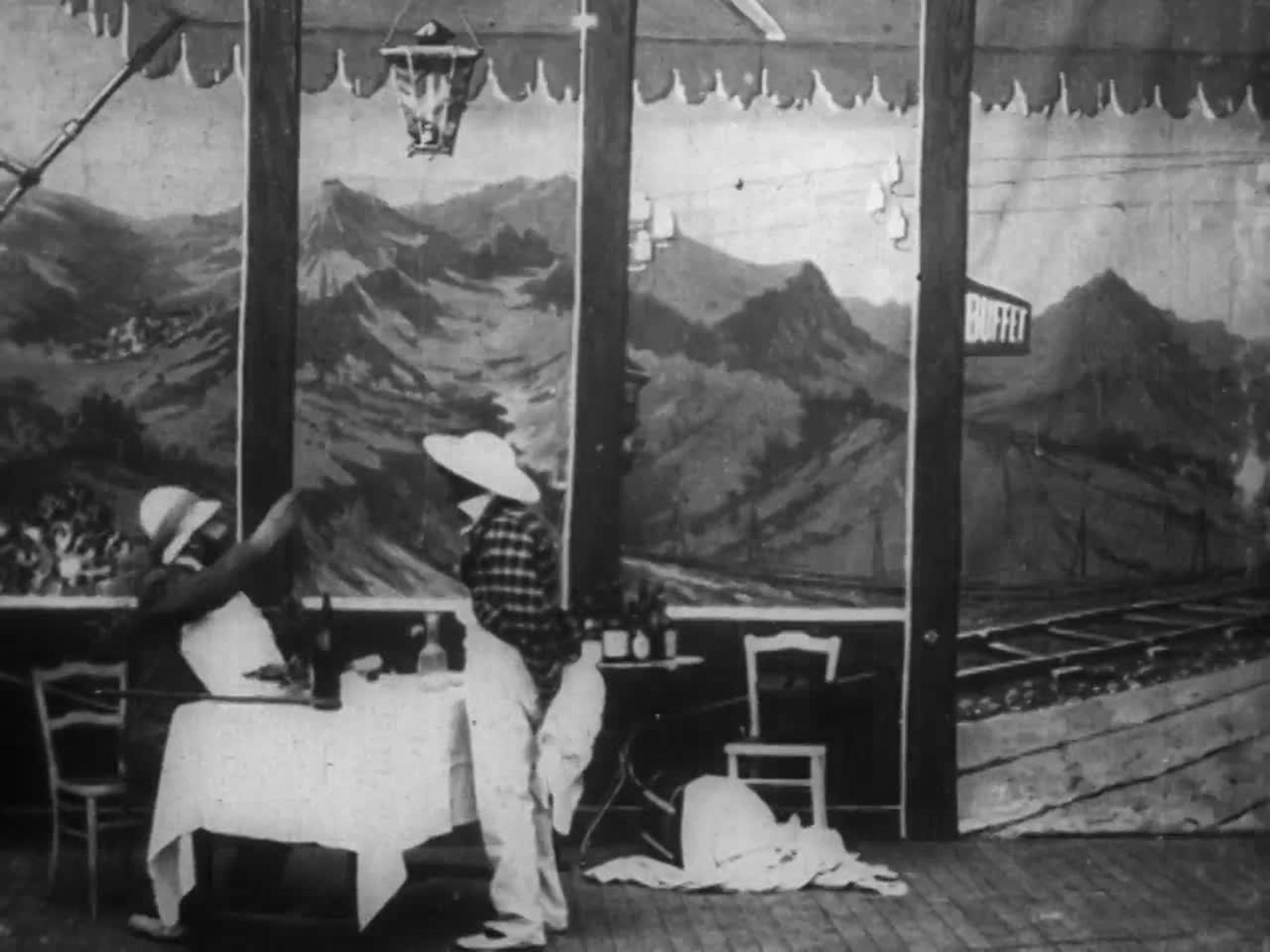

Over the next three months, Paul and Acres made a slew of short films for the Kinetoscope, many based on sporting and cultural events, with titles such as Oxford & Cambridge University Boat Race; Arrest of a Pickpocket, which has the distinction of being the first dramatic film made in England; The Derby; Comic Shoe Black; Boxing Kangaroo; Performing Bears; Boxing Match; Carpenter’s Shop; Dancing Girls; Rough Sea at Dover; and Tom Merry, Lightning Cartoonist. These early films were seen for the first time at the Empire of India Exhibition at Earl’s Court, where Paul had installed a number of his Kinetoscopes.

The following year in 1896, Paul – who had at this point parted company with Acres – began to get more ambitious, and hit upon the idea of of projecting images on to a screen, to be viewed by many people at the same time, rather than through a Kinetoscope eyepiece. This essentially formed the basis for the birth of the modern cinema age.

Paul also filmed the topical events of the day and his film of the Derby of 3 June 1896 was shown at two major London theatres within 24 hours of the event taking place, thus marking the true beginning of the news film

Paul was the first to sell apparatus, films and projection equipment to the wider market, including to French director Georges Méliès, as well as launching Britain’s first film studio, where he produced the country’s largest number of films annually until the end of the 1890s. He made Britain’s first fiction film The Soldier’s Courtship (1896), frames from which are held in the collections of the National Science and Media Museum and a reconstruction will be screened as part of the exhibition. He also created the first two-shot film in which the camera cut between scenes in Come Along Do! (1898), and the earliest on-screen titling and intertitles, which can be seen in Scrooge, or Marley’s Ghost (1901).

Although many of these films are lost, around 80 are known to survive, says Sarah Bemand of the British Film Institute, who adds to the praise heaped on Paul’s contribution to the birth of cinema. She says: “A contemporary of the Lumière brothers, Robert Paul created the foundations for what we take for granted as cinema today, leading the way in so many different areas as an engineer, inventor, exhibitor, producer and filmmaker.

“The most prolific British filmmaker of the early film period, he made over 700 films of which 80-plus films are currently known to survive, although more are being discovered in film archives around the world.”

Alongside the Science and Media Museum’s exhibition, the BFI has released several of the films on a new digitised collection available on the BFI Player, including Fun on the Clothes-Line, from 1896, A Miner’s Daily Life (1904) and Extraordinary Cab Accident (1903).

John Barnes writes: “Paul also filmed the topical events of the day and his film of the Derby of 3 June 1896 was shown at two major London theatres within 24 hours of the event taking place, thus marking the true beginning of the news film. Paul was one of the first English producers to realise the possibilities of cinema as a means of presenting short comic and dramatic stories and to this end he built the first studio in England, with an adjacent laboratory capable of processing up to 8,000 feet of film per day.”

During his time in the industry he continued to experiment with new techniques, subjects and formats, including distributing films of foreign locations, hand colouring films and capturing panning shots. Throughout his film career Paul produced more than 800 titles, quitting the business in 1910 and destroying the negatives of many of his films, his motive for which remains a mystery. He would return to his original career as a pioneer of scientific instrument making and industrialist.

The Forgotten Showman exhibition at the Science and Media Museum also looks at the work of his contemporaries in the film industry, such as the Lumière brothers.

Visitors can see original objects showcasing innovations in cinema, including Paul’s Theatrograph projector, the 35mm camera made and used by Paul to film the Diamond Jubilee Procession of Queen Victoria in 1897, and original frames from one of his earliest works, Incident at Clovelly Cottage, made with Birt Acres in February 1895.

The exhibition has been co-curated with Professor Ian Christie, a renowned film historian and professor of film and media history at Birkbeck University of London. Prof Christie has worked with artist ILYA to produce a graphic novel telling Paul’s story. His reference book on the subject is also due to be published later this year, titled Robert Paul and the Origins of British Cinema.

Prof Christie says, “Paul has been ignored for too long in British histories and internationally. Given the scale of his innovation and enterprise, it’s time we brought these to wider attention, and there’s nowhere better than the National Science and Media Museum, which houses some of Paul’s surviving equipment.

“It’s important too that young people today, living through the digital media revolution, can draw inspiration from knowing that Britain led the original film revolution in the mid-1890s, which is why we’ve also told Paul’s story in a graphic novel, Time Traveller: Robert Paul and the Invention of Cinema.”

“The Time Traveller” is an important part of the Robert Paul story, as in October 1895 he tried to achieve his most ambitious scheme yet, which proved a step too far for the technology he had available, if not his imagination.

Taking inspiration from the science fiction novella published by HG Wells that year, Paul’s “The Time Traveller” would have been a multi-screen immersive experience that would have catapulted viewers through time and space. It never happened, ultimately, but it did set Paul on the road of further pursuing the idea of projecting images and taking movies out of the Kinetoscope.

Science and Media Museum curator Toni Booth adds: “Paul was able to achieve all this through a combination of his engineering abilities, business acumen and entertainment skills, taking hold of an opportunity right at the cusp of a new industry which today it would be difficult to imagine a world without.”

And, she says, it is not just a story of technical ability, but a very human tale that appears to be worthy of a movie in its own right.

And like any good story, he provided a dramatic ending by abruptly leaving the film business in 1910 and burning his negatives

Booth says: “The eventful if short film career of Robert Paul covered illegal activities, rivalries, spectacle, industry, imagination and innovation. His work established industry practices which affected both film makers and audiences alike.

“And like any good story, he provided a dramatic ending by abruptly leaving the film business in 1910 and burning his negatives. Only around 10 per cent of his output now survives, possibly another reason why he is not a familiar name in popular history”.

This year also marks the 10th anniversary of Bradford Unesco City of Film. The internationally recognised title celebrates the rich film history and contribution to cinema of the National Science and Media Museum’s home city. The exhibition will pay tribute to Bradford’s film heritage, including the work of the Riley brothers who established their Magic Lantern business in the city in the 19th century, a precursor to the technology pioneered by Paul.

Alongside the exhibition, Pictureville, the museum’s newly launched independent cinema operation, will be hosting a special “Breathless Sensation” programme, showcasing spectacular cinema from the past 100 years which left original audiences awestruck and breathless, with screenings of King Kong (1933), Mary Poppins (1964) and The Matrix (1999).

Although not quite the household name he perhaps should be, Robert Paul did leave a legacy that after his death helped people with the same sort of technical drive and vision as he had. John Barnes writes: “When he died on 28 March 1943 at the age of 74, he left industrial shares valued at over £100,000 to form a trust – the RW Paul Instrument Fund – administered by the Institution of Electrical Engineers, of which he had been a continuous member since 1887, the income to be used primarily for the provision of instruments of a novel or unusual character to assist physical research.”

* The Forgotten Showman: How Robert Paul Invented British Cinema opens today at the National Science and Media Museum in Bradford, West Yorkshire, and runs to 29 March 2020. Entry is free – for more information go to scienceandmediamuseum.org.uk/whats-on/forgotten-showman

* The BFI Robert Paul collection can be viewed at player.bfi.org.uk/free/collection/robert-paul

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks