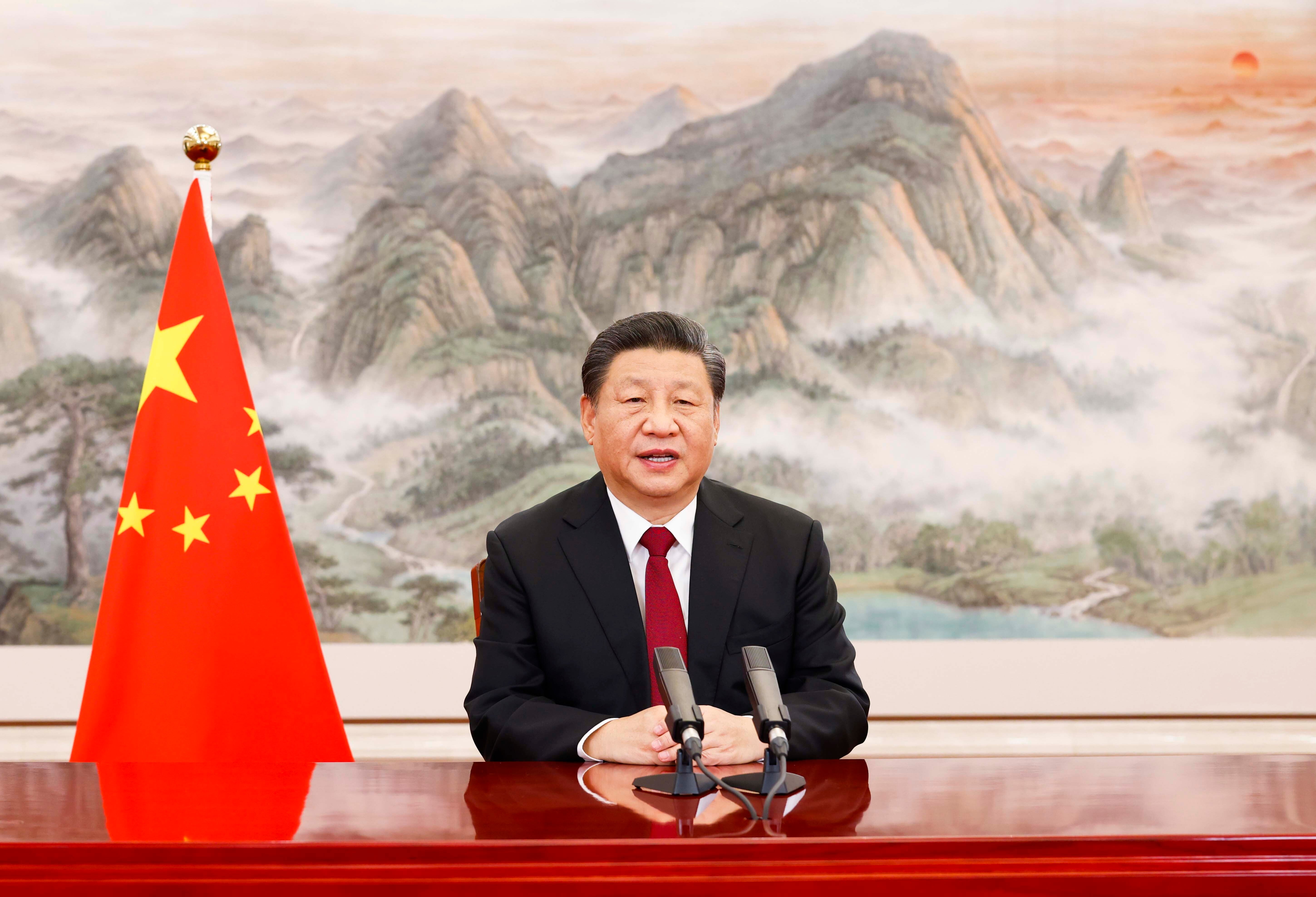

Xi Jinping: The relentless rise of a leader the whole world is watching

Beijing may be currently hosting the Winter Olympics, but there are many more reasons why every move Xi makes is being closely observed, writes Chris Stevenson

Xi Jinping’s vision for his country is based around a “great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation”. Both internally and on the international stage, nationalism is central to what he wants – and it doesn’t hurt it tends to help myth-building around the president, who is in the process of building a unique position for himself in the pantheon of Chinese leaders.

The Winter Olympics currently taking place around Beijing are a perfect example of the state of China under Xi and the changes he has enacted since the country was awarded the right to host the 2022 edition of the Games in 2015. Xi had become general secretary of China’s Communist Party in 2012 and took the ceremonial title of president the next year. By the time the host of the 2022 Winter Games were announced, it was still expected that the Olympics would make one of the last major events of the Xi presidency as he nears the end of what has been his second and final term. However, Xi is now expected to embark on an unprecedented third term near the end of this year – with term limits having been removed in 2018.

The Olympics are aimed at impressing both a global audience, but now also cement support at home ahead of a congress in October or November that will keep him as head of the Chinese Communist Party, state and military. China has claimed its first gold medal, already matching the total from Pyongyang in 2018, having ploughed funds into facilities and talent. The winter Games are not traditionally as strong for China as the summer version – having finished in the top 10 nations just once in 2010 – but Xi will expect a return on the investment.

Xi has been busy during the first few days of the Games, even with a number of nations such as the US, UK, Canada, Australia and India participating in a diplomatic boycott, including meetings with Russia’s president Vladimir Putin (Friday) and Pakistan’s prime minister Imran Khan (over the weekend).

As they met, Xi and Putin called on the west to “abandon the ideologised approaches of the Cold War”, said Nato should rule out expansion in eastern Europe, denounced the formation of security blocs in the Asia Pacific region, and criticised the recent security pact between the US, UK and Australia. The meeting was the 38th between the pair since Xi came to power.

The diplomatic boycott from western nations is based around China’s human rights record, particularly the repression of the Uyghurs and other Muslim minorities – a situation which has led some US politicians to label Beijing 2022 the “genocide Games”. Xi and his government have always denied accusations of repression (despite mounting international pressure), with a Uyghur athlete helping light the Olympic flame seemingly an act of defiance.

Authoritarianism is a crucial part of Xi’s leadership, with various crackdowns having been initiated over the years. A much-hyped crackdown on corruption by party officials proved popular with the people, but there were certainly plenty of political rivals caught up in it. In 2015, more than 200 lawyers and legal aides who helped activists and members of the public challenge official abuses were detained. Following protests in Hong Kong that were initiated in 2019 over a proposed extradition law, but became a broader call to protect democracy, a national security law was imposed in 2020 – a move widely criticised as eroding the autonomy that Hong Kong had been promised when the UK returned the city to Chinese rule in 1997. Pro-democracy figures have also been imprisoned, including Jimmy Lai, the former publisher of the Hong Kong-based Apple Daily newspaper, which shut down under government pressure. Activists Joshua Wong, Agnes Chow and Ivan Lam were also given sentences for their involvement in the 2019 protests.

On the mainland, surveillance of China’s 1.4 billion people has been expanded, with a “social credit” system tracking every person and company and punishes infractions from pollution to littering. A zero-tolerance approach to Covid-19 was adopted when the virus appeared, something that is clearly visible in the tough security arrangements over isolation and testing during the Beijing Winter Games (and the lack of spectators) – but that policy was not enacted without accusations of Xi’s government suppressing information and punishing doctors who tried to warn the public.

Xi’s consolidation of power may have initially caused some surprise internationally – but it is clear he is a canny operator who has been entrenched in China’s political machinations since he was young. Born in Beijing in 1953, Xi enjoyed a privileged upbringing and schooling as the second son of Xi Zhongxun, a former vice premier and guerrilla commander in the civil war that brought Mao Zedong’s communist rebels to power in 1949. However, unlike many other so-called “princelings” who are prepared for the upper echelons of China’s society, Xi faced his father being purged and imprisoned in 1962 prior to the Cultural Revolution (he was rehabilitated in the 1970s before being sidelined in the 1980s).

Xi was sent to the countryside for “re-education” and hard labour for a number of years in the remote and poor village of Liangjiahe at the age of 15. This period would feature heavily in later myth-building – with an official biography later published by the state-run Xinhua news agency stating: “He suffered public humiliation and hunger, experienced homelessness and was even held in custody.”

While Xi himself has spoken few times about this time – potentially preferring to leave room for rumour – he has said it shaped him.

“People who have little contact with power, who are far from it, always see these things as mysterious and novel,” he is reported as saying in 2000. “But what I see is not just the superficial things: the power, the flowers, the glory, the applause. I see... how people can blow hot and cold. I understand politics on a deeper level.” He also told a magazine in 2001: “Knives are sharpened on the stone. People are refined through hardship... Whenever I later encountered trouble, I’d just think of how hard it had been to get things done back then and nothing would then seem difficult.”

Having finally been accepted as a member of the Communist Party in 1974, he first worked as a local party secretary in Hebei province, before moving on to more senior roles – including party chief of Shanghai, China’s second city and financial hub. With his profile rising, he was then handed a spot on the party’s top decision-making body, the Politburo Standing Committee. The leadership would follow. His mother, now in her mid-90s, has remained a presence, with Xi’s biography stating that: “As a filial son, Xi takes walks and chats with his mother, holding her hand”.

In a world of bureaucrats, a little star power was added to Xi’s profile when he married Peng Liyuan (after a short earlier marriage to Ke Xiaoming the daughter of a diplomat). Peng gained popularity as a soprano singer and is China’s most high-profile first lady since Chairman Mao’s wife, Jiang Qing.

This comparison to Mao is important for Xi – and certainly the cult of personality being built up around him as echoes of Mao. Xi has shared the distinction with Mao of being the only leaders who have had their political ideas mentioned by name in the country’s constitution: this “Xi Jinping Thought” is now on the curriculum and will is aimed at ensuring “teenagers establish Marxist beliefs”, according to the Ministry of Education. The guidelines include labour education “to cultivate their hard-working spirit” and education on national security.

As Xi’s hold over China has grown, the country has become more assertive internationally. It has antagonised Japan and other nations by trying to intimidate democratic Taiwan – which Beijing believes belongs to it – and by pressing claims to disputed sections of the South and East China Seas. Xi has also sought to make China a technological power, although western nations have grown concerned by the possible security concerns of using such products.

China’s economy has provided the backbone for much of this posturing – as well as being able to deal in acts of soft power by investing in Asian and African projects. Economic growth is now slumping – with one factor being Covid-19 – although some internal reforms within areas like the property sector and orders to use Chinese-made components in manufacturing (when at greater cost) have also had an effect. It is such economic pressure that may stop Xi from offering more than kind words and offers of political partnership to leaders like Putin. China may be one of Russia’s most important trading partners, but the US and members of the EU are more valuable to Beijing.

Xi knows further growth will not come without issues – the president warned that the nation faced many challenges in an address to the National People’s Congress in early 2021. But that speech contained a message to the world about China’s growing self-confidence.

“No one can beat us down and choke us,” he said.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments