How What3Words is helping people to navigate the world

Andy Martin spoke to Chris Sheldrick about his company making difficult navigation easy with pin-point accuracy

Chris Sheldrick got his first job around the age of five. Growing up on a farm in Hinxworth, a village outside Cambridge, he had to run down the track to wave to wayward delivery drivers trying to find his place, which didn’t even have a proper address, and guide them in. Now, as founder and CEO of what3words, he’s still showing people the way all over the world, from Hinxworth to Mongolia.

He feels as if he’s been trying to direct traffic all his life. He used to be a bassoonist who studied at King’s College, London, and the Royal Academy. But an accident when he punched a hole in a glass door and permanently damaged his left hand, meant that at 21 he pivoted to production and specifically tour manager. In practice, this meant 10 years of trying to convey addresses of venues to roadies. Even if they don’t run out of petrol (the number one cardinal sin), roadies, in my experience (having been one), invariably blow it one way or another. The turning point for Chris Sheldrick was one stressful day in 2012 when he got a call from a roadie in Italy. “I’ve arrived!” he says. “But where’s the venue?” (I am deleting the profanities, but you can stick them back in, fairly liberally).

The guy had driven all the way from London with a lorryful of boy band paraphernalia. Having mis-transcribed the GPS coordinates, he found himself an hour north of Rome instead of an hour south. And halfway up a mountain. It was, says Sheldrick, “the most stressful day of my career”. Somehow, with a show-must-go-on attitude, he managed to get it sorted out just in time.

“Whenever we gave an address,” says Sheldrick, “It would take people to different places depending on what app they were using.” Even something like finding the back entrance of the O2 proved a major hassle. For a while, he tried to get people to use latitude and longitude. Then, surely, there was no possibility of getting it wrong. Ever since the days of Captain Cook, navigators all over the world have been using that system. But, back on dry land, getting roadies to take 16 coordinates on board (and I would have been just the same) proved to be “bizarrely difficult”. The thought that ultimately occurred to Sheldrick was: “How can I make it simpler?” And roadie-proof.

In January 2013 he was in Cambridge visiting an old friend of his, a mathematician called Mohan. They used to program the old BBC Micro computer together when they were kids. Sheldrick gave a heartfelt account of his struggles to his old friend and said, “Can’t we come up with a better way?” They rejected alpha numeric code (too random). “Can’t we use words?” says Sheldrick. “How many would we need?”

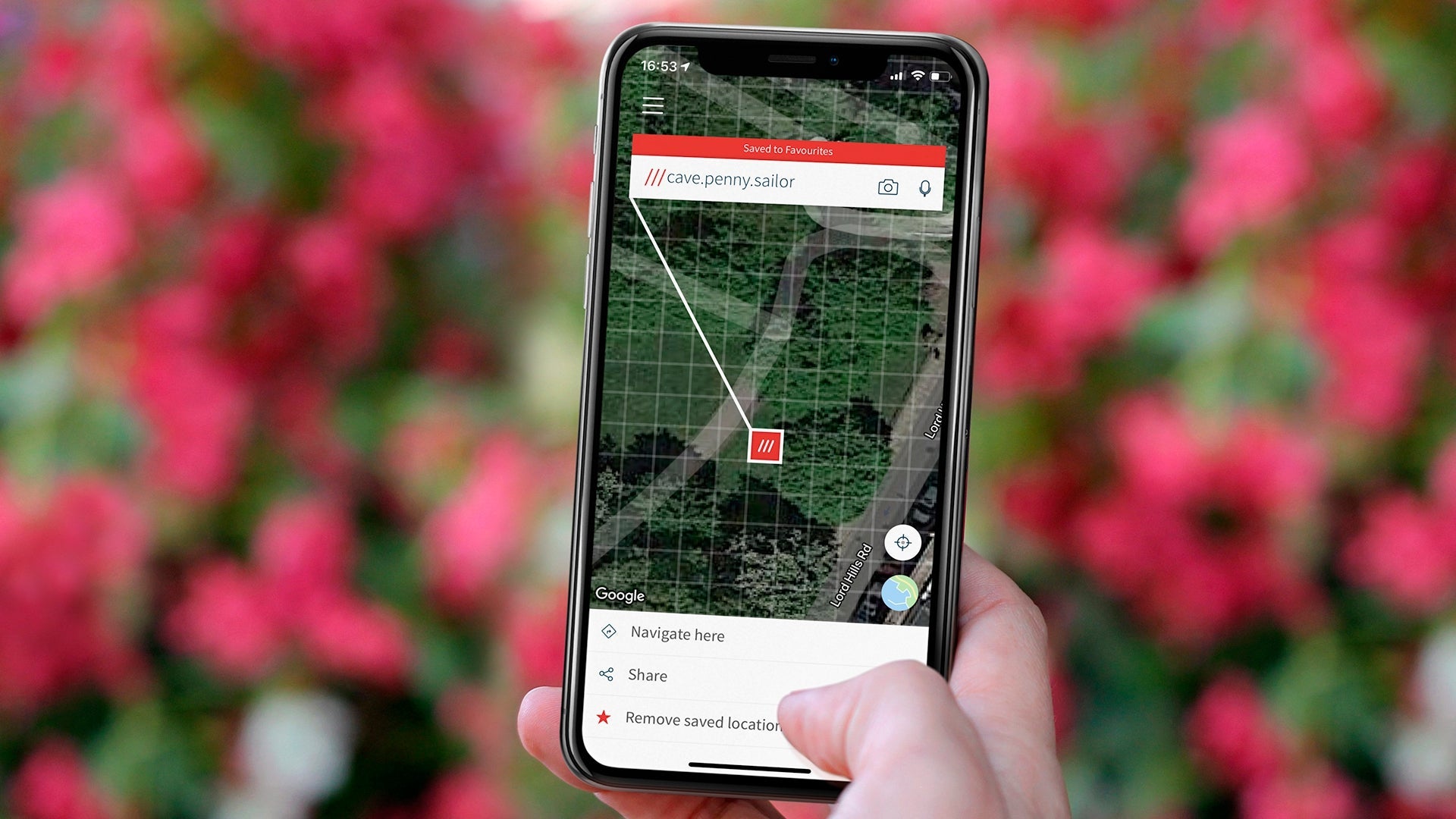

Mohan did a back of an envelope calculation: the surface of the entire world can be divided into 57 trillion 3x3 metre squares. Assume that there are (roughly) 40,000 usable words. If you allow combinations of three words, that gives you 40,000 to the power of three, which equals… 64 trillion. So, they agreed, three words, in various combinations (let’s say, table.chair.spoon – off the A1, north of Newcastle – or cats.dogs.camels – an address in Cincinatti), should be enough to divide the world up into chunks that even the least competent roadie should be able to locate.

Formerly hard to find places are now a piece of cake. And should you break a leg on the top of Ayers Rock (or Uluru), you are at snake.removes.gymnast

Sheldrick set about compiling his corpus of 40,000 words. First he excluded all the obscenities. Then he took out nearly all long words, except he left a few for places in Antarctica (so Antarctic Great Wall Station is backbiting.hadron.conglomerate). “Sesquipedalian” is gone, alas, even in Antarctica. “Bassoon” on the other hand was given a high ranking – “Because I’m biased.” All the homophones (“hear” and “here”) had to go, so as not to give roadies an excuse for going to the wrong place. After five months – three solid hours every night working through the dictionary – the whole world had been successfully boiled down to a large set of three-word strings. The most common words were used for addresses on land, the less common words to cover the ocean.

Now, Sheldrick says, the process is a lot slicker. They’ve just done Welsh, having hired a team of 50 lexicographers. Mandarin Chinese was the most difficult, because of the tonal system. In French they allow the infinitive (parler, for example), but not the past participle (parlé) because it sounds identical. And if you try parlez the website and the app will point you back to the infinitive.

A lot of countries – including England – struggle when it comes to addresses in rural areas (such as Sheldrick’s childhood home). Japan is fantastically eccentric in its address system: they number the buildings in the order they were built, so you can have 61, 7, and 15 next door to one another. Mongolia, which had a chaotic or non-existent address system, bought into the what3words system.

“That was a pinnacle moment in our evolution,” says Sheldrick. He met a man in China who had just bought a third of the Mongolian postal system, and wanted something better. Now you can post a letter in Mongolia that has just a name plus three words underneath it and it gets delivered (they actually put this to the test in an episode of QI – what3words passed with flying colours). The biggest bank in Mongolia has put its three-word address on its credit cards. “It’s part of the fabric of Mongolian society now,” says Sheldrick. Even Lonely Planet uses what3words addresses in Mongolia.

Emergency services in this country are using the what3words system, so they can find not only obscure addresses but also people who have been injured in a forest or up a mountain. Always providing you still have a phone signal, you don’t need to get to a landmark, three words will do. Places in Jersey and on the Isle of Man, formerly hard to find, are now a piece of cake. And should you break a leg on the top of Ayers Rock (or Uluru), you are at snake.removes.gymnast. You never know.

If you buy a new Mercedes car, you can now speak the magic three words, and the satnav will take you exactly where you want to go. Guaranteed. You won’t even need a roadie.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments