Despite accelerating wage rises, Britons are getting poorer

With inflation continuing to run hot, people’s pockets are still empty, says James Moore

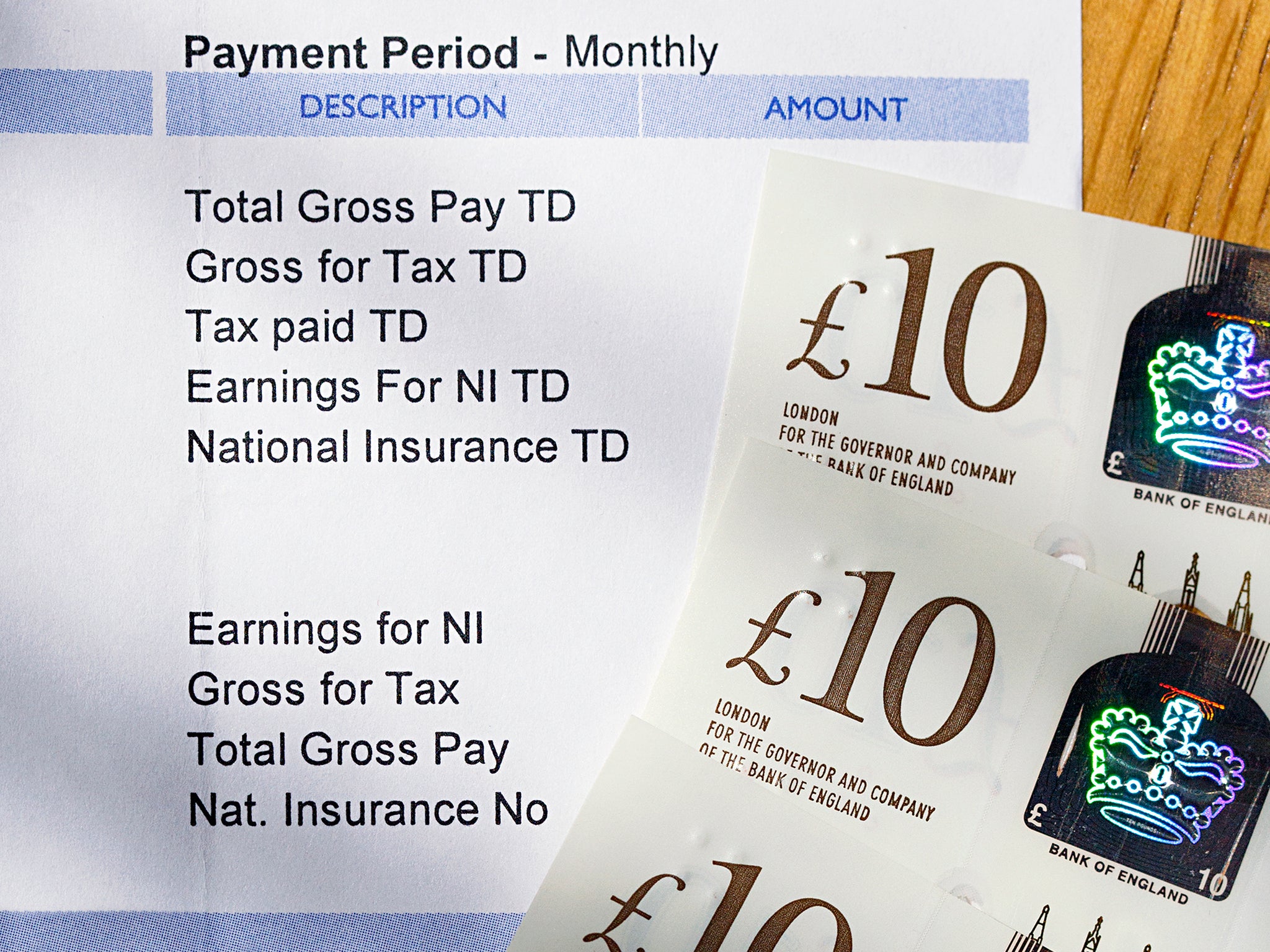

Wages are rising at a surprisingly rapid pace, according to the latest official labour market release from the Office for National Statistics. At 7.2 per cent, excluding bonuses, this is the biggest number in 20 years outside the pandemic period (the rate was 7.3 per cent between April and June 2021).

Good news for workers? Only up to a point. With inflation continuing to run hot – 8.7 per cent in the 12 months to April – signs of wages closing the gap ought to be welcomed, but in real terms, wages are still falling.

Adjusted for inflation, pay fell by 1.3 per cent annually for the February-to-April reporting period (this particular dataset uses a three-month term). When bonuses are included, pay fell by 2 per cent.

Remember too that inflation has different effects depending on where you sit on the wage scale. Food prices are rising at close to 20 per cent; this hits those at the bottom harder because food makes up a higher proportion of their household budgets.

A chunky rise in what the government describes as the national living wage (accurately described as the minimum wage) was a big contributor to the overall number. The hourly rates moved up to £10.42 in April for those aged 23 and over, a near 10 per cent increase. But even that likely won’t be enough to cover the personal inflation rates of minimum wage employees, largely because of those food prices.

“Family budgets can’t take any more pressure,” said TUC general secretary Paul Nowak. “It’s no wonder workers are reluctantly taking strike action to defend their living standards. They’ve been backed into a corner and pushed to breaking point.”

Nowak is not wrong; Britons are getting poorer, fast. This has been the case for well over a year. Those who borrow are about to get poorer still.

The Bank of England will see nothing good in these figures. Huw Pill, its chief economist, recently created a storm he said this in a podcast interview: “Somehow in the UK, someone needs to accept that they’re worse off and stop trying to maintain their real spending power by bidding up prices, whether higher wages or passing energy costs through on to customers.”

His choice of words was criticised governor Andrew Bailey. But Bailey himself once cautioned people against seeking higher pay rises. Pill may have been guilty of no more than saying the quiet part out loud.

The rate-setting Monetary Policy Committee, of which they are both members, simply has to get inflation under control. But there is a debate to be had about these numbers – namely, whether they really provide evidence of the 1970s wage-price spiral that the Bank fears.

Higher wages certainly have an inflationary impact. But there are other factors behind Brtiain’s stubbornly high rate. Food prices, which have started to replace energy as the chief culprit, are influenced by factors mostly outside of the bank’s control, including the war in Ukraine, Brexit, poor harvests in Spain and so on.

Part of the reason underlying core inflation, which excludes food and energy, is proving stubborn is down not to the greed, or rather the needs, of workers but of their bosses. The phenomenon of “greedflation” – companies forcing through price rises not because of higher wage bills but to boost their margins – is clearly playing a role.

The MPC has nonetheless made its views clear; it sees high wage rises as a problem. Sterling was up sharply in response to the figures and parts of the City have started to bet on a bumper 0.5 point rate rise at the next MPC meeting, speculation which these figures will fuel. A rise of 0.25 points feels more likely, on a split vote, but the higher number can’t be ruled out.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks