Bad blood between Taylor Swift and a private equity group may entertain – but the music industry faces bigger problems

The boom in streaming has fuelled the dispute between Swift and Shamrock Capital but it favours established artists, writes James Moore

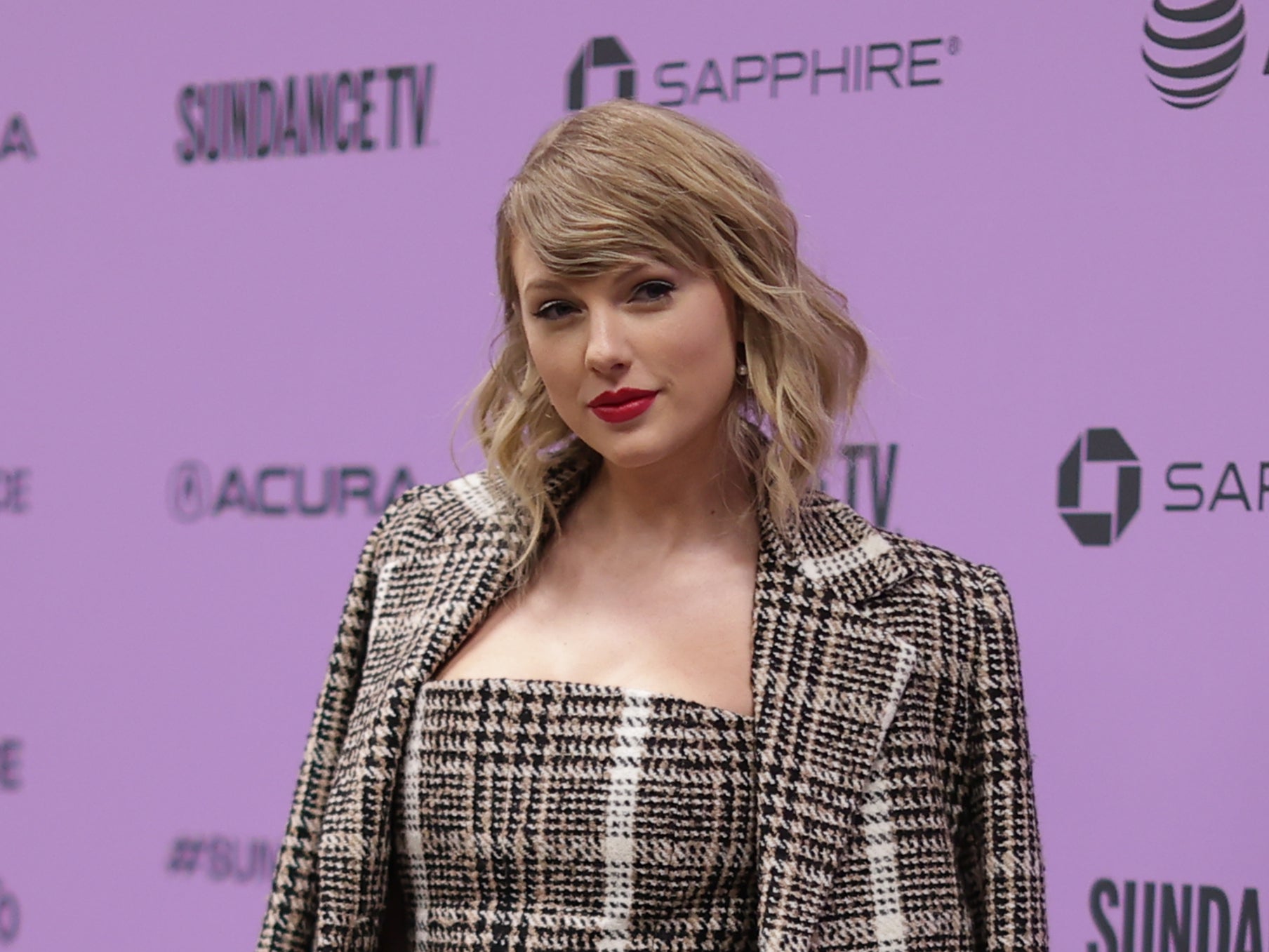

There was already “bad blood” to spare between Taylor Swift and Scooter Braun, the manager of her rival Kanye West among others, when the mogul bought the company that owned the masters to a string of her multi-platinum albums via his Ithaca Holdings. Now he’s sold them to a private equity firm for $300m (£226m), there’s enough of the stuff to drown in.

The background is that Swift signed a deal with a label called Big Machine in 2004, giving it the ownership of said masters in return for an advance to kick-start what has become an astonishingly successful (and lucrative) career. This isn’t at all unusual for artists who are just getting going.

Enter Braun, whom Swift has accused of “bullying” among other things. He bought the label last year with the help of a private equity backer, the Carlyle Group, better known for the presence of world leaders such as John Major and the late George HW Bush among its alumni.

Swift’s recordings have become part of a very expensive game of pass the parcel because of the boom in streaming. As a result, those masters can be counted upon to sprinkle gold dust upon their owners for years to come.

Streaming might yield just a fraction of a penny per play but when your music is played to the extent that Swift’s is it adds up to vast sums.

Shamrock Capital – the buyer – would of course do better by cooperating with and making a partner of the artist, something it would clearly like to do not least because as a writer Swift can stymie some of their attempts to capitalise on their new property. That could include vetoing the licensing of songs for use on TV or in film. She says she’s already done that by turning down repeated offers from various parties interested in using “Shake it Off”, one of her more famous tracks.

This could greatly devalue Shamrock’s property. It seems set to continue. In a tweeted statement to her fans on Twitter, Swift said she would refuse to play ball while Braun could continue to take a cut of the earnings from her work. Ithaca will reportedly be able to do that by qualifying for future payments if her songs hit revenue targets (again, not unusual in deals of this type).

Private equity firms don’t generally enjoy this sort of publicity and it’s not the first time Swift has deployed it as a very effective weapon. When Braun arrived on the scene she made her unhappiness clear and openly appealed to Carlyle to intervene.

The firm duly found itself at the centre of both a pop culture and a political storm. Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez took Swift’s side tweeting: “Private equity groups’ predatory practices actively hurt millions of Americans. Their leveraged buyouts have destroyed the lives of retail workers across the country, scrapping 1+ million jobs. Now they’re holding Taylor Swift’s own music hostage. They need to be reigned [sic] in.” Senator Elizabeth Warren also weighed in.

Wisely, the firm tried to broker a deal. Without success.

Now Shamrock’s feeling the heat. Swift even says she’s started to re-record her old songs, which could further devalue the firm’s investment (and potentially inhibit the future payments to Ithaca).

Or maybe not, because a big, publicity-backed release of Swift’s new recordings of old songs could just as easily serve to encourage streams of the old ones. It’s called the law of unintended consequences.

The recovery of recorded music that has catalysed the dispute has been remarkable. Japanese investor SoftbBank, for example, had a bid of $8.5bn for Universal Music rejected in 2013 despite analysts suggesting it was $2bn more than the company was worth. Owner Vivendi recently sold a 10 per cent stake in a deal that put a notional value of $33bn on the business, the revenues from which rose 6 per cent over the first nine months of 2020 despite a 10 per cent fall in physical and a 20 per cent fall in download sales.

But streaming bolsters the haves, like Swift, at the expense of the have-nots. It encourages a flight to the familiar at the expense of the new and unheard: the chances are you’re going to ask your smart speaker to play what you know, the famous songs at the front of your mind.

Covid-19’s killing of live music has served to further limit the opportunities of newer artists to get to the front of fans’ minds.

They may very well look at the invidious position Swift was in when she signed her first deal with envy.

UK Music – which today publishes its annual Music by Numbers showing the sector contributed £5.8bn to the UK economy in 2019 – is appealing for help to get back on its feet because it needs it.

Swift’s power makes her catalogue the subject of a multimillion-dollar tug of war. But the row will eventually be resolved, probably in her favour because these things always are and because Shamrock is going to learn that she has at her command weapons it won’t easily be able to deflect.

Meanwhile Taylor Swift 2.0, whether she’s in Nashville, London, or LA, is probably struggling to eat. Even getting ripped off by a record company is but a distant dream.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments