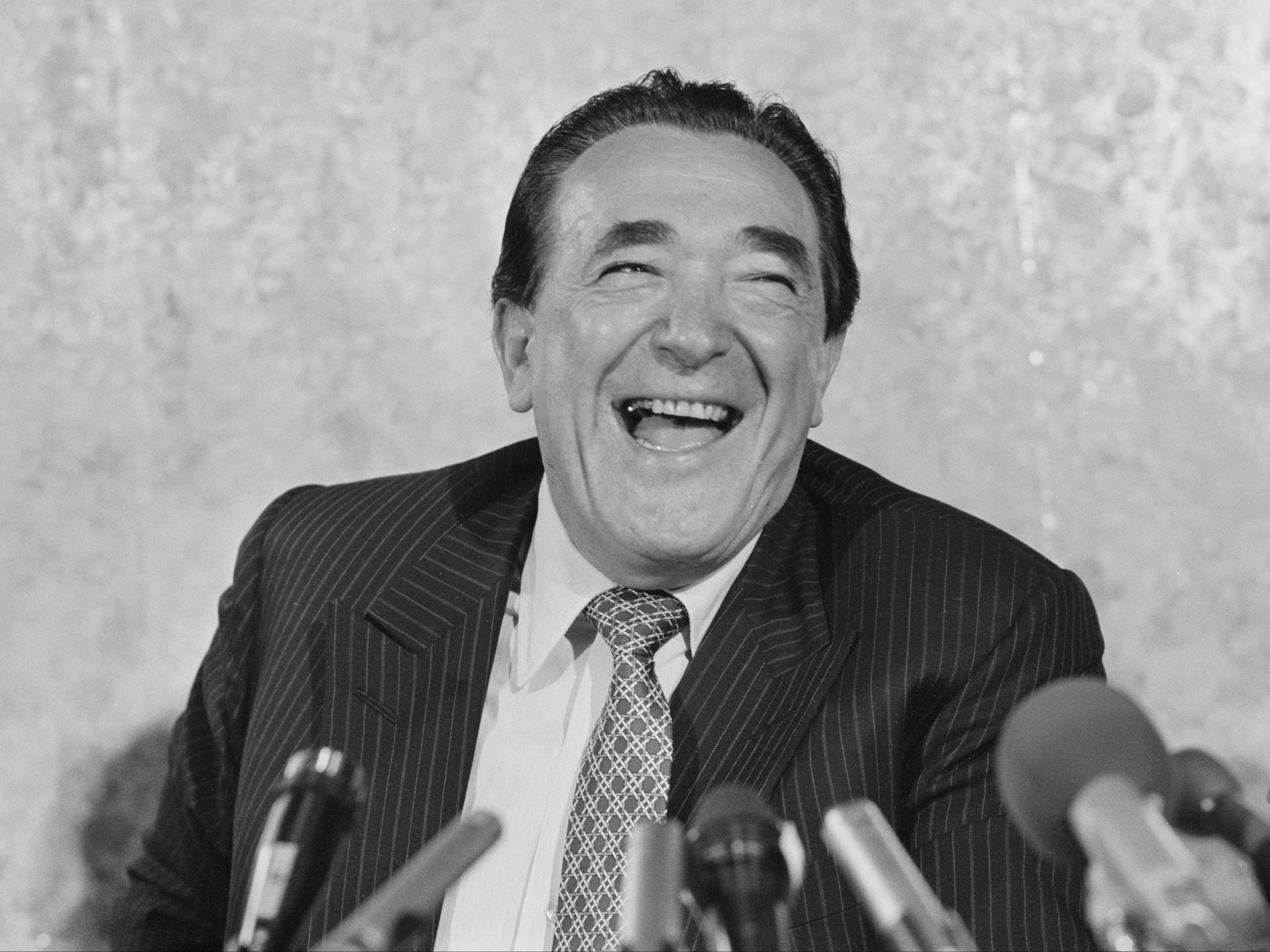

Robert Maxwell’s rise and demise carries the same weight as it did 30 years ago

We used to make fun of the media mogul; he kept us entertained for years – but his business success is undeniable. He was a billionaire after all, writes Chris Blackhurst

I once interviewed Robert Maxwell in his underpants.

I had to go and see him about a business deal he was doing, and the only time the late tycoon could see me was while he was getting changed for dinner. I was taken in, past the grand portals of his private quarters at the top of Maxwell House in Holborn, next door to the Mirror headquarters, and ushered into his bedroom. He came out of the bathroom, wearing a white dress shirt and minus his trousers.

While he proceeded to lecture me in that booming, gravelly voice of his, he finished donning his dinner suit. In answer to what you may be thinking, they were white, Y-fronts, and they were vast.

The next occasion I was there was soon after his death. I went to meet his son Kevin for what was billed as the first interview with a close family member. Kevin was sitting on the floor next to a bookcase, surrounded by piles of books. As we talked, he was boxing them up.

I remember expressing my condolences at his loss, “A great man”. Kevin nodded his appreciation.

We were fooled by Maxwell. Not by his foul temper and bullying, boorish behaviour – there were tales galore of his outlandish acts. No, we were duped by his crookedness.

Reading Fall – the Mystery of Robert Maxwell, the new book by John Preston, it all comes back. We used to mock Maxwell’s ridiculous promises, the shameless self-promotion and ridiculous vanity, his impossible pomposity. He kept us entertained for years.

Behind the craziness, though, was his business success. Whatever you thought of Maxwell, there was no denying he’d built an empire – he was a billionaire, the Sunday Times Rich List said so, at a time when there were very few billionaires.

Towards the end, we were aware he was overextended. Increasingly, his companies appeared to defy gravity. Shortly before his actual demise, a few analysts and commentators had started to raise questions – they’d defied the permanent threat of libel and were pointing to weaknesses in the accounts. But their alarms were not especially shrill.

Then Maxwell vanished from his yacht, Lady Ghislaine, in 1991, and his body was found floating in the sea. That was the cue for the public unravelling. Even so, it did not occur immediately. When I saw Kevin there was little hint of the fraud revelations that were to come.

It seems odd, tramping over such familiar ground again. Some, doubtless, will query its pertinence. It’s true, also, that for a younger generation, Ghislaine, his daughter who is wrapped up in the Jeffrey Epstein sex abuse allegations, is better known.

Some have said that Preston’s account offers nothing new. It’s highly readable, but for those who followed the Maxwell saga closely, it’s old territory and therefore of little interest.

I disagree. Maxwell’s rise and demise carries the same weight as it did 30 years ago.

Finance, law, accountancy remain peopled by too many who will do their client’s bidding, who make it their job to provide the client with what they want

What’s shocking was the compliance of those around Maxwell in his deceit and theft. For anyone seeking a primer as to how the financial, legal and accountancy professions can go out of their way to serve anyone, how judgment and honesty play second fiddle to the pursuit of lucre, it is here.

We know Maxwell was a villain. He did not, however, act alone. At every turn he was assisted by a legion of professional advisers, by enablers who greased his path and made his illegality possible. That’s what jumps out from Preston. It’s the ease with which Maxwell moved hundreds of millions of pounds from the left hand to the right, as he raided the Mirror pension fund for yet more cash to prop up his ailing concerns elsewhere – and the fact that nobody in the City and Wall Street so much as raised an eyebrow, let alone sought to block him.

The sums were eye-wateringly enormous then, and they remain large now. He took £35m, he bunged in another £50m, he grabbed £200m. No one among his highly-paid hangers-on appeared to mind or care.

It is inconceivable they did not realise what he was up to; their degree of compliance was total.

Interesting word, compliance. It has two meanings. There’s the formal one, which means complying with the law, with the regulations. Banks have whole compliance departments staffed with, in the case of the biggest global corporations, thousands of compliance officers.

But compliance has another, less legal, definition, which is to acquiesce or, as the Cambridge English Dictionary says: “The state of being too willing to do what other people want you to do.”

This is what Maxwell tapped into. For all the attention heaped on the former type of compliance, to the extent that the late rogue would not recognise a modern bank or law firm or accountants, has much altered since his time regarding the latter sort? The City and Wall Street may say that it has but they would: no is the answer.

Finance, law, accountancy remain peopled by too many who will do their client’s bidding, who make it their job to provide the client with what they want. That’s why the Maxwell story is still so relevant today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

1Comments