How South Bank became Europe’s largest arts complex

South Bank was once a purely industrial part of London and is now a shimmering constellation of concert halls, galleries, theatres and more, writes Andy Martin

Is the South Bank actually south? “Look at the map,” says Nic Durston. “It’s further north than Victoria.” The South Bank may be south of the Thames, but the river hangs a sharp left (and therefore south) after Blackfriars so, in effect, the South Bank can reasonably claim to be more central to London than say the West End.

The other thing I was not fully aware of until I spoke to Durston, CEO of the South Bank Employers Group, is that the South Bank is Europe’s largest arts complex – a shimmering constellation of concert halls, galleries, theatres and more – all under the gaze of the London Eye. It stretches from Blackfriars Bridge upriver to Lambeth Bridge and encompasses the Oxo Tower and Gabriel’s Wharf at one end and the Garden Museum at the other. With a skatepark nestled in the middle of it all, beneath the Purcell Room. And a handy hospital. Not to mention the network of big corporations and small businesses and all the people who live there.

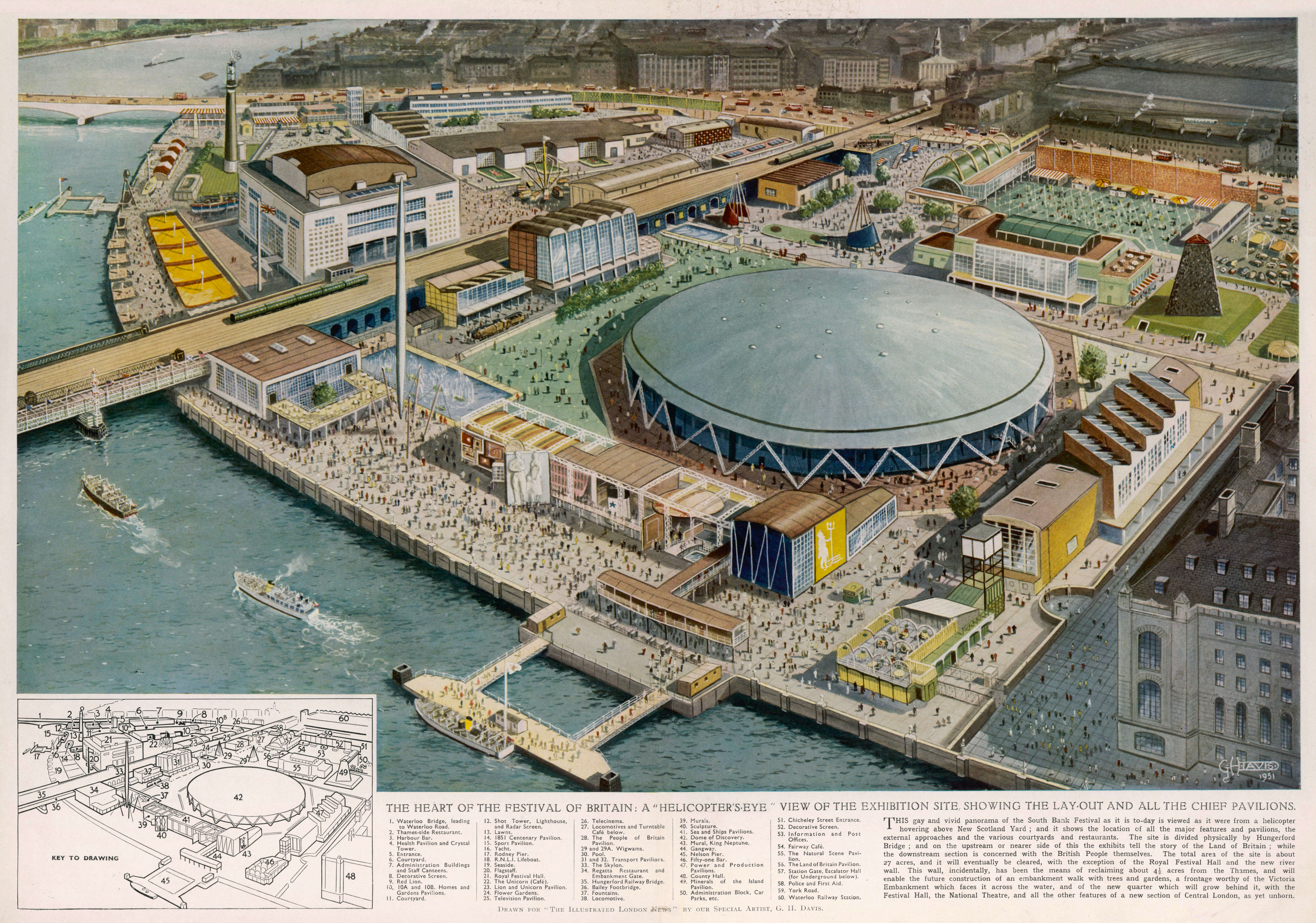

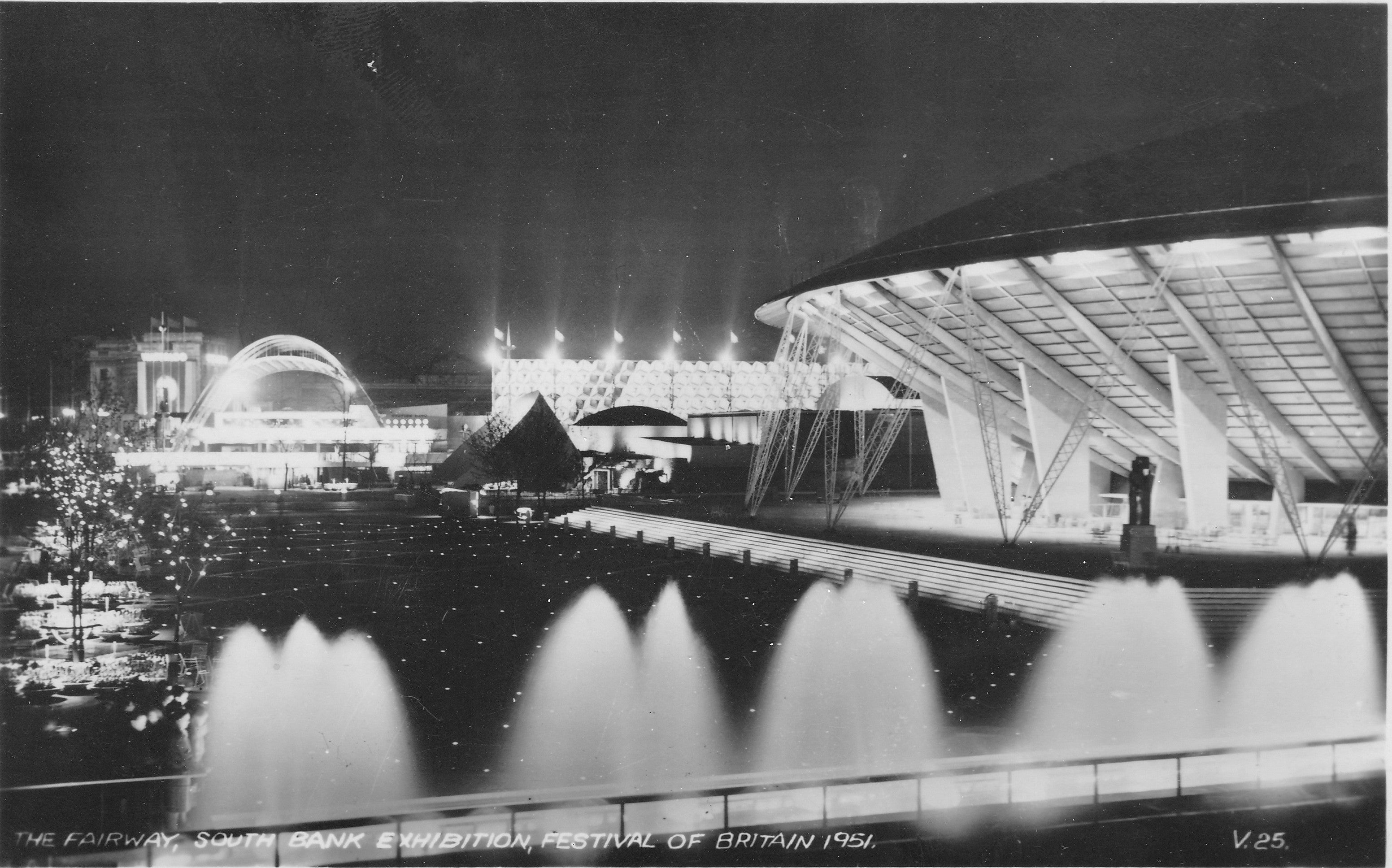

And it stretches back in time too. What is now South Bank was once a purely industrial part of London, an unlovely collection of wharves and tanneries and breweries all along the Kinks’ “dirty old river”. And then it got the living daylights bombed out of it. The cratered wasteland was reborn in 1951 for the purpose of the Festival of Britain, conceived as a “tonic to the nation” after the rigours of the Second World War and postwar austerity, and harking back a century to the Great Exhibition of 1851. Ravaged by war, the whole area was reclaimed and rebuilt, with the Royal Festival Hall replacing the Red Lion Brewery. But the celebrations and the sense of creativity extended beyond the South Bank to Battersea, Poplar, St Paul’s and corresponding events in Glasgow and elsewhere. So the South Bank became a microcosm not just of London but of the whole of the UK.

The return to normal will take time, but lots of what London has to offer is still here

This is the 70th anniversary of that great nationwide party, and the South Bank is still all about regeneration and renewal, especially now that everything is gradually reopening, including – in a socially distanced way – the Hayward Gallery and the Purcell Room. “This place is good for the soul,” says Durston, “but it’s important to the economy too.” According to a recent analysis, each job on the South Bank generates another 2.5 jobs across the economy. In a normal year, according to the London Plan, the area as a whole generates around £5bn. The arts cluster – the Southbank Centre, the National Theatre, the Old Vic, the Young Vic, the Rambert – boasted a GVA (Gross Value Added) of £110m in 2018-19. But that shakes out as £255m, taking into account indirect revenues. Needless to say, everybody’s income took a dive during the pandemic. A National Theatre production had to open and close on the same night when lockdown kicked in. One figure that caught my eye: overseas visitors were formerly 43 per cent of the crowds; during the last year or so that went down to 1 per cent.

Nic Durston studied geography at University College, London, in the late Eighties, and went on to work in conservation for English Heritage and the National Trust, but he was irresistibly drawn back to London. “I realised I wanted to work for London, not just live in London,” he says. Durston has worked in the east (Hackney), west (Kensington), north (around the Olympic Games) and now finally south (if it is south). SBEG (South Bank Employers Group) was set up in 1991 as a coalition of organisations, from the arts to Shell to St Thomas’s Hospital, concerned to stave off the decline of the South Bank and intent on harnessing all that creativity.

Durston doesn’t get involved in what’s coming on next at the National Theatre – although he gets to go to a lot of plays and concerts – but he does have a wide-ranging brief, including liaising with all the various stakeholders, evenly spreading largesse around, security, picking up litter, and making sure there were enough “pods” of portable toilets around for roaming pedestrians during the pandemic (“You want to avoid public urination”). He’s got an eye on minimising the Covid risk factor too, and is organising more outdoor events and installations and performance projections – the “inside out” project.

As we stroll along the Queen’s Walk, Durston – like a more urban Attenborough – guides me through the tangled “economic ecology” that binds together all this free access and commerce, the smaller riverfront cafes, restaurants and bookshops that flourish under the canopy of the National Theatre (“Lasdun’s masterpiece”). They’re all subtly interconnected and interdependent. Durston has been here six years and has not just overseen the development of the website, southbanklondon.com, but made sure that the graphic map that adorns the information boards incorporates that distinctive southward kink in the river.

WeWork has its European HQ in the South Bank. So too IBM, which is currently relocating but within the neighbourhood. But the South Bank is not all about big business. The non-profit social enterprise that is Coin Street oversees the Oxo Tower (where the original beef extract was once manufactured) with all its social housing and community performance spaces and “makers”. Gabriel’s Wharf with its collection of boutiques and pop-ups and veggie eateries and Sax, “the world’s largest saxophone store”, has a similarly indie ethos. At the chic end of the spectrum, the Harvey Nichols restaurant sits atop the Oxo Tower with views across the river to St Paul’s and the City.

At the centre of the South Bank is Jubilee Gardens, once the site of the “Dome of Discovery” during the Festival of Britain, which bore a happy resemblance to a recently landed flying saucer and was the precursor of the Millennium Dome. Alas it morphed into a carpark and then an off-on quagmire/dustbowl, but it is now restored to what Durston calls a “free, open democratic space”, with lots of greenery and benches and a new kids’ adventure playground. This area was also the site of the magnificent Skylon, a silvery floating vertical structure that was the outstanding icon of the Festival of Britain and was ultimately dismantled on the orders of Winston Churchill because he feared it symbolised socialism. The lamented Skylon is remembered, however, by the restaurant of that name in the Royal Festival Hall.

The London Eye has taken over what is now one of the best-known landmarks in London. But like the Dome of Discovery, it was originally conceived as a temporary structure. The wild idea of a giant ferris wheel was first floated for the purpose of the millennium. Originally owned by British Airways, it is now run by Merlin Entertainments and sponsored by lastminute.com. When I was passing by it boasted longer queues than any other attraction.

I ask Durston about the “Let’s Do London” campaign, launched by the mayor in May. “The return to normal will take time,” he says. “But lots of what London has to offer is still here.” Only someone who is tired of life will be tired of the South Bank, as Dr Johnson didn’t quite say.

I return to the South Bank in the evening to catch the Illuminated River – Leo Villareal’s brilliant nighttime neon transformation of the bridges. It’s beautiful and it’s free. As I head back towards Waterloo station, I have that old Kinks song playing in my head: “As long as I gaze on Waterloo Sunset I am in paradise.”

This year’s BFI London Film Festival, with dual London hubs on South Bank and in the West End and venue partners across the country, runs from 6-17 October. Tickets are on sale on Wednesday

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments