It is frightening just how easily investors were seduced into the cult of WeWork

There is nothing unique about WeWork – all you need is an empty office block to set up your own shared working space – so why did so many investors get involved with Adam Neumann’s cult-like business? Asks Chris Blackhurst

Walking into a shared office space in the City last week I could have been forgiven for supposing I was entering a WeWork.

There was the similar decor (complete with slogans inspiring me to lead a better life), the food and drinks counter, full meeting rooms, casually dressed folks wearing headphones sitting hunched over laptops. It looked, felt, smelt like a WeWork. Except it wasn’t. It was a recently divided-up building, of which there are now thousands in in cities and towns everywhere.

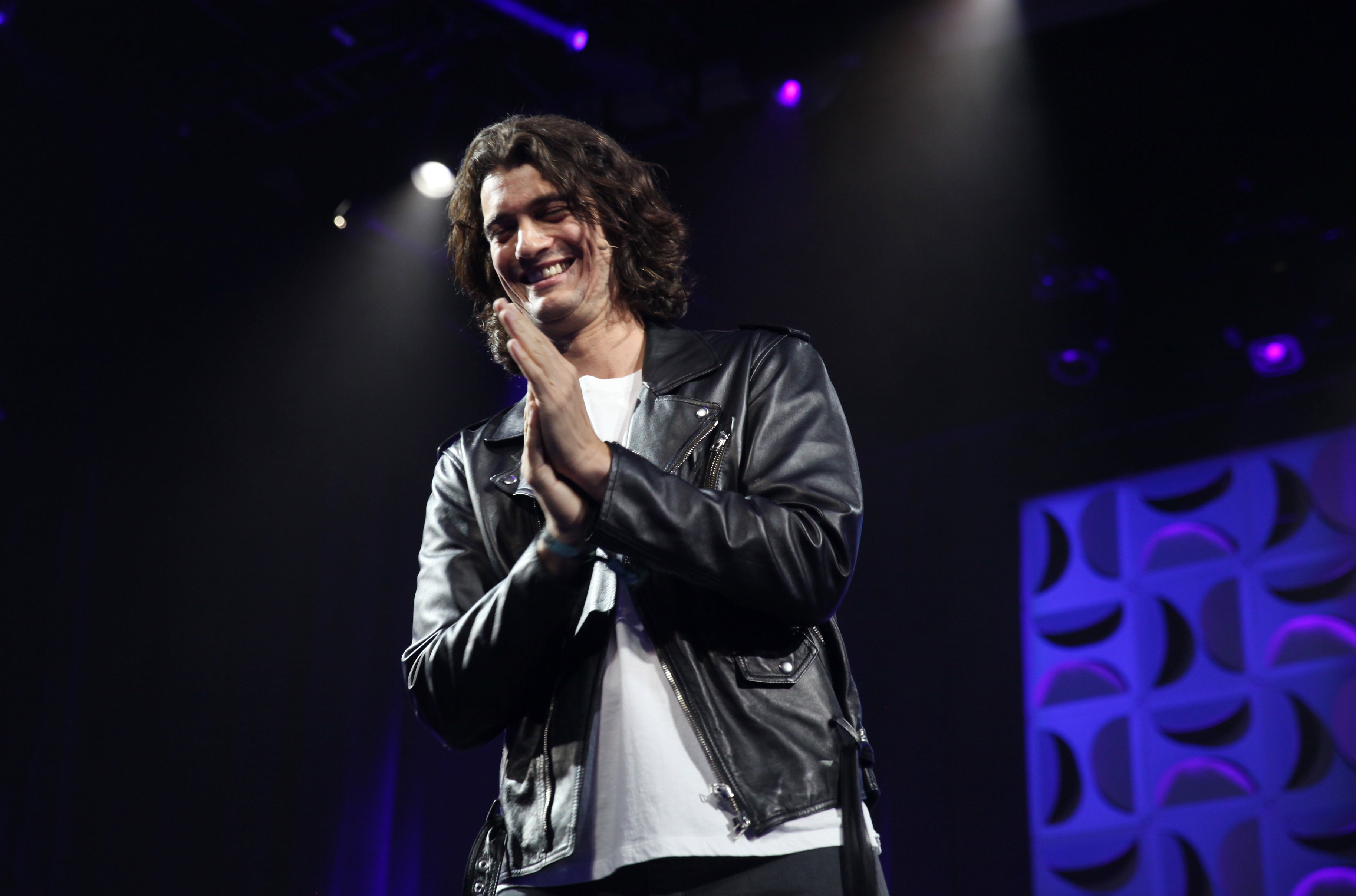

I had the dubious pleasure of meeting Adam Neumann, the WeWork founder, when he opened in London. Dubious because Neumann spoke and I listened.

His address was on the brilliance of Adam Neumann. I did manage to interject that I could not see what was so special. There was nothing to stop me from taking over an empty block and doing the same. What he was providing was hardly unique. Not so, he said. I lacked WeWork’s “secret weapon – we know how to provide exactly the right culture”.

He showed me a video of WeWork’s New York members at a summer camp. They were sat on decks and around campfires, against a backdrop of lakes and big skies. The message was clear: join WeWork and you too could enjoy their beautiful lifestyle. As I watched, Neumann murmured: “We want you to do what you love, to find the creative in you and let it out.”

He came across as more ripped rock god, in tight T-shirt and jeans, than capitalist property baron; a self-styled Messianic visionary rather than pedlar of desks for a few hundred pounds a month.

At the time, WeWork was only a few years old but it was already worth $10bn. Incredibly, it went on to reach $47bn, only to crash to earth on the back of revelations about Neumann’s excesses, including smoking pot on the corporate jet, exhorting staff to down tequila shots on work time, running up increasingly heavy losses and treating the firm as one giant personal ATM.

Neumann, however, sold the model of WeWork as belonging to tech – when it was nothing but a simple property play

It was not only the City offices that prompted the memory, but also a new book, The Cult of We: WeWork and the Great Startup Delusion by Eliot Brown and Maureen Farrell, the Wall Street Journal reporters who exposed the megalomania of Neumann (he ruminated about becoming “President of the world”). The book recounts brilliantly the full horror of his ego and the unquestioning adoration of his followers, who squandered billions trying to make the WeWork dream a reality, notably Japan’s SoftBank and its creator, Masayoshi Son. As they say, it really was like a cult.

Neumann managed to exit with a fortune; his backers were not so lucky, seeing their investments plummet. There exists still, a much-reduced WeWork. Meanwhile, shared offices have popped up all over.

What’s frightening is just how easily seemingly savvy investors were seduced by the hype. They believed that he was selling something unique and that he was a genius – no matter that Mark Dixon with his Regus brand had got there years before, albeit without the touches that Neumann brought to WeWork. The success of Dixon and Regus, though, should have served as a warning. Strip away WeWork’s standard bare bricks, wooden floors, bar, preachy signs, IT support (all of which were themselves easily replicated) and what was left were tenants in shared offices, for which, thanks to the ascent of the laptop and tablet, and more flexible patterns of working, were in growing demand.

Neumann, however, sold the model of WeWork as belonging to tech – when it was nothing but a simple property play. His supporters wanted to believe it was brilliant and disruptive, straight out of Silicon Valley, and therefore attracting the sector’s soar away valuations.

It was not only Dixon and Regus – lessons from history were also ignored. It was as if the dotcom bubble of the late Nineties had never occurred. I remember then being shown round a nondescript former office block on the edge of the City, just like the one I was in the other day. Back in the late Nineties, it was hailed as an “Internet Incubator.” What this comprised of were floors partitioned into units. Each one was home to an e-commerce start-up. The people had all adopted the same dotcom dress code of black jeans, black T-shirts and trainers. Upstairs there was a lounge, with a bar supplying an array of coffees and teas and alcohol, and on the roof, there was a terrace with a DJ. Not long after my visit, dotcom stocks nosedived, the result of wary funders finally waking up to the crazy forecasts. The building I toured was turned into apartments. Two decades later, came the rise and fall of WeWork.

WeWork had no USP. Anyone could churn out the WeWork formula. One landlord told me recently how they took the best from Neumann’s company and added to it. Where Neumann assumed he knew what people wanted, they researched the market, talking to would-be occupiers. The result is a shared office space with higher ceilings, higher quality fittings than a WeWork, a snack bar supplying a simple selection of soup and sandwiches rather than the range that Neumann would traditionally supply. They cut back on the faux community stuff – theirs is a place for work and if needs be, some networking; they don’t ram it down throats. They’re left with a packed building that is making them a solid, tidy profit.

They’re now looking to roll out others, but carefully and slowly. Where Neumann charged headlong, they’re treading cautiously.

Neumann’s rapid expansion was WeWork’s undoing. He called it “scale” to me, as if it was somehow mysterious. He had scale alright, but critically that meant lots of WeWorks, it did not mean economies of scale. Opening a branch, adding to the list, cost money.

The pandemic has seen demand for flexible, relaxed working environments soar. In London alone, there is an estimated shortfall of 100,000 such spaces. Not everyone wants to WFH. They may not have the room; they may desire a change from being at home. But neither do they want to go into a formal office setting – so something in-between is the answer. You see, Neumann was a prophet after all.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments