We can no longer deny the need for a global currency

The climate and Covid-19 crises show that our internal monetary system is failing – something must change soon, writes Phil Thornton

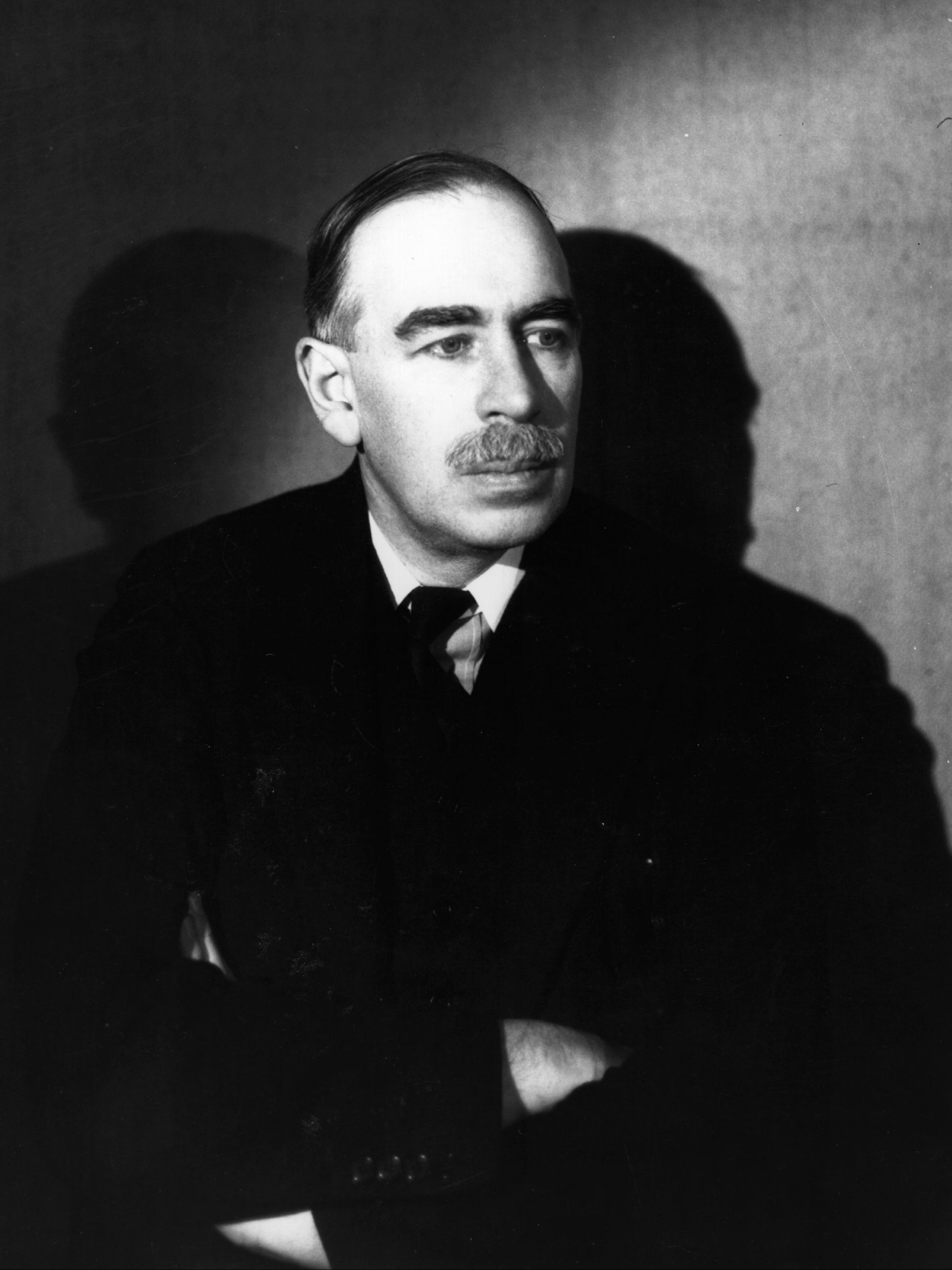

A global reserve currency, which was the brainchild of British economist John Maynard Keynes more than 80 years ago, may finally become part of the monetary system in the wake of Covid-19 and the fallout from the chaos in Afghanistan.

Keynes proposed a supranational currency called a “bancor” in 1940 that would act as a supranational currency in which all nations would settle their trade. The idea was vetoed by the Americans, who wanted the dollar as the reserve currency.

However, stresses on the financial system 50 years ago led the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to create an arcane instrument called the special drawing right (SDR). It is not in fact a currency but a reserve asset to help countries during financial crises. As Mark Plant, chief operating officer of think tank CGD Europe, puts it: “SDRs are promises, not money.”

After months of pressure, the IMF’s members finally agreed earlier this month to create another $650bn (£472bn) worth of SDRs to help countries with the financial impact of Covid. Last Monday these were credited to countries in line with their existing share in the ownership of the IMF.

Except a small number — including Afghanistan.

But even for those countries that will qualify, those that need it most will receive the least. Wealthy nations such as the US, the UK and EU states receive $433bn (£315bn), middle-income countries such as China get $212bn (£154m), while low-income developing countries will receive about $21bn (£15bn) – a significant addition to their international reserves, but hardly enough.

These poor countries that exchange their SDRs for “hard” currency such as US dollars can buy vaccines and pay nurses or pay off the debts they have racked up to cope with the crisis.

This raises the question of what wealthy countries, and some middle-income countries with lots of reserves, should do with the SDRs that they do not need. Ted Truman, a former US Treasury official and an expert on international finance at the think tank PIIE, points out that SDRs now make up 8 per cent of global assets, so we are talking about serious money.

Here it gets very complex. They could give them away to individual countries, but the political climate at the moment is particularly hostile to foreign aid.

Furthermore, when a country gives SDRs away, its holdings fall below the country’s allocation, which means it pays interest on the difference. Currently, that is just 0.05 per cent but it is based on market rates, so could rise rapidly, causing headaches for conservative central banks.

Maybe now is the time to go back to the future and design a supranational currency

If countries lend them then they can demand them back if rates spike up (creating problems for the recipient) but if they donate them then they are liable for those payments in perpetuity.

Assuming that a loan is more appealing, the next question is to whom. They could pass them on to bodies that deliver assistance to struggling countries, such as the IMF’s Poverty Reduction And Growth Trust (PRGT). But the PRGT makes loans that come with conditions attached.

The IMF has talked about establishing a new “resilience and sustainability trust” that would lend at cheaper rates and longer maturities. But those are still loans, which poor countries will be reluctant to take on.

Another option according to Oxford Policy Management think tank is to use new SDRs to fund grants from donor countries for an early replenishment of the International Development Association, the arm of the World Bank that works with poor countries.

Maybe now is the time to go back to the future and design a supranational currency. Covid-19 is not defeated, the climate emergency is causing havoc across the world.

When leaders meet for the COP26 climate summit in Glasgow in November they will be under pressure to find new forms of climate finance. Between now and then a summit of IMF members and meetings of leaders from the G20 and G7 will also be held.

Ten years ago, the IMF suggested exactly that in a detailed paper that never received any political support. In the wake of the global financial crisis, the Strategy, Policy and Review Department suggested building a global currency issued by a global central bank and called bancor “in honour of Keynes”.

The authors were ahead of their time, noting that a global central bank could serve as a lender of last resort, providing much needed systemic liquidity in the event of adverse shocks and “more automatically than at present”.

At the time, economist Zhou Xiaochuan, then governor of the People’s Bank of China, suggested that using the SDR as the pivotal international reserve currency would provide “the light in the tunnel for the reform of the international monetary system”. The cracks caused by the Covid-19 and climate crises should let that light in.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks