Coronavirus: It’s time for Corona 0.7 – we have to give to those in need

In 2020 Britain, people who are visibly starving are going to food banks. Chris Blackhurst says that a nation that has forgotten its proud history of altruism must give more, starting with the UN’s modest suggestion

Every day, amid the misery inflicted by coronavirus, there are tales to gladden the heart. Charitable donations are pouring forward, from some of the richest people on the planet, from celebrities, and from ordinary people who are determined to help. In the UK, 99-year-old “Captain Tom” Moore has become a folk hero, raising a fortune for the NHS with his pledge to walk 100 laps of his garden before his 100th birthday.

It is truly uplifting, and in the case of Second World War veteran Tom, positively tear-jerking. Sadly, more, much more, is required.

One of the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic is to bring into sharp relief the desperate inequality that besets us. The schism was growing and becoming ever evident, but the crisis is highlighting it like never before.

So far, there have been few signs of social unrest but figures that show the poor are being hit the hardest by the virus, and pictures of overcrowded slums trying to follow social distancing and good hygiene when they don’t have even running water will only serve to stoke tension.

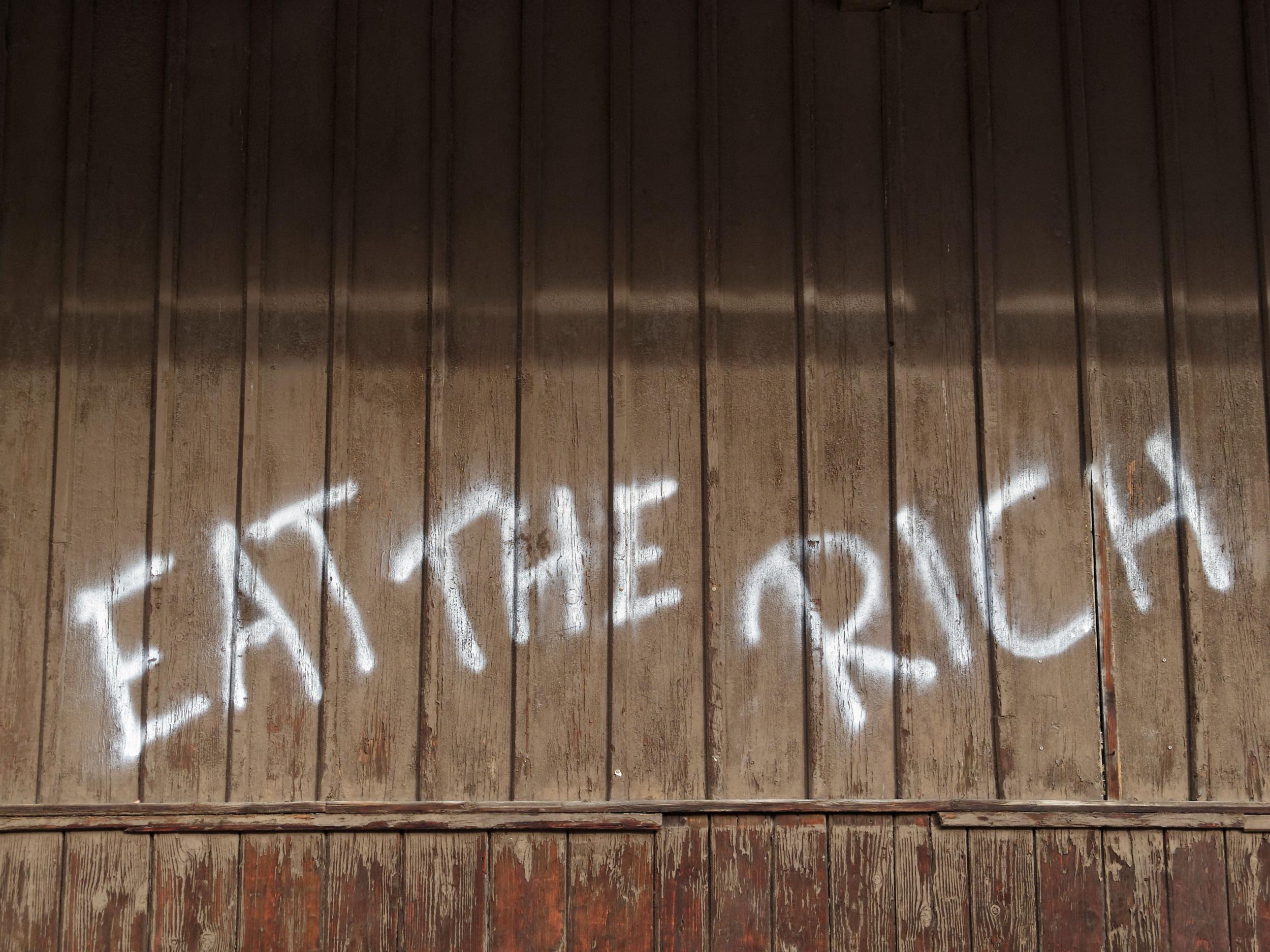

The revelation that hedge funds have made £1.5bn in profits by shorting UK shares during the crisis, by effectively willing them to fall, has been met with fury. Sprayed on a wall near where I live, the old, Class War slogan of “Eat the Rich” has suddenly reappeared, in vivid, huge letters. If they are to avoid abuse and worse, the wealthy have to dig a lot deeper.

For the UK that is no easy ask. As a country our record on charitable giving is lamentable. We lag far behind other nations, notably the US, where philanthropy is regarded as a duty – a price to pay for making money.

It was not always like this in the UK. A glance round the centre of any British city or town will reveal grand civic buildings named after Victorian industrialists, halls and libraries bearing boards of donors, schools and former poorhouses named after local entrepreneurs.

But whereas in the US that tradition was maintained and, as time has gone on, has hardened, in the UK it virtually dried up. The advent of the welfare state and state education in Britain were viewed, incorrectly, as lessening the need.

Our tax system has never made donating advantageous or easy. And a collective cynicism has taken hold, so that anyone making a large gift is often regarded as pursuing gesture philanthropy, of not really believing in what they’re supporting, of being “after something” – either currying favour or public recognition, or both. Certainly, it does not help that charitable giving is a tried and tested method of obtaining an honour: be seen to back something worthy with a pile of cash, and a gong will surely follow. Instead of earning gratitude, donating can provoke distaste and suspicion.

Making people pay the same level of 0.7 per cent from their gross income would mean that someone on the average full-time salary of £37,000, would pay £21.60 a month

We do not have much faith, either, in our public bodies. Respect for them has waned so that when we come to consider whether to hand over our cash, we do not always trust them to spend it wisely.

Somehow, post-corona, we need to turn back the clock. Already, prior to the outbreak, health and social care, housing and education were under great strain and unable to cope. Food banks were growing in number – now they’re everywhere and bigger in size.

Something must change. The government must move to foster philanthropy. That’s all very well, but by the same token, how much should we each pay?

In 1970, the United Nations set a target for the richest economies of setting aside 0.7 per cent of gross national income in development aid for the poorer nations. It was a proportion later built into British law. Down the years, we’ve met the limit, and frequently we’re one of the few countries to do so.

The objective is not without controversy, however. For some it’s viewed as a threat to our sovereignty, a foreign imposition, a move designed to divert our funds overseas when it could be used for domestic deserving causes, and there are questions too as to what the cash is actually used for, and if it reaches the most deserving.

Making people pay the same level of 0.7 per cent from their gross income would mean that someone on the average full-time salary of £37,000 would pay £21.60 a month.

Others suggest we ought to aim higher. In Islam, one of the religion’s five pillars is zakat: the requirement that Muslims who are eligible to pay must donate at least 2.5 per cent of their wealth to charity. Elsewhere, there have been calls for members of the Church of England to donate 10 per cent of their income to the church. That’s also the level put forward by the Oxford philosopher Toby Ord for his Giving What We Can movement.

We can argue about the right amount. But for now, and given the straitened, pressing times for many, we could at least begin small – it would be a start. We could do worse than to follow the UN lead. As a businessman friend told me this week about how shocked he was to witness something he thought he’d never see in Britain in 2020, people who were visibly starving using a food bank, the money is desperately needed. Corona 0.7 cannot come soon enough.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments