Christmas should be the time for department stores to shine

In the battle to entice a new generation while reconnecting with former customers, department stores mustn’t try to be all things, writes Caroline Bullock

If there was ever a time when shoppers might be tempted to cut beleaguered department stores some slack and reacquaint themselves with the unique experience they offer, it’s now.

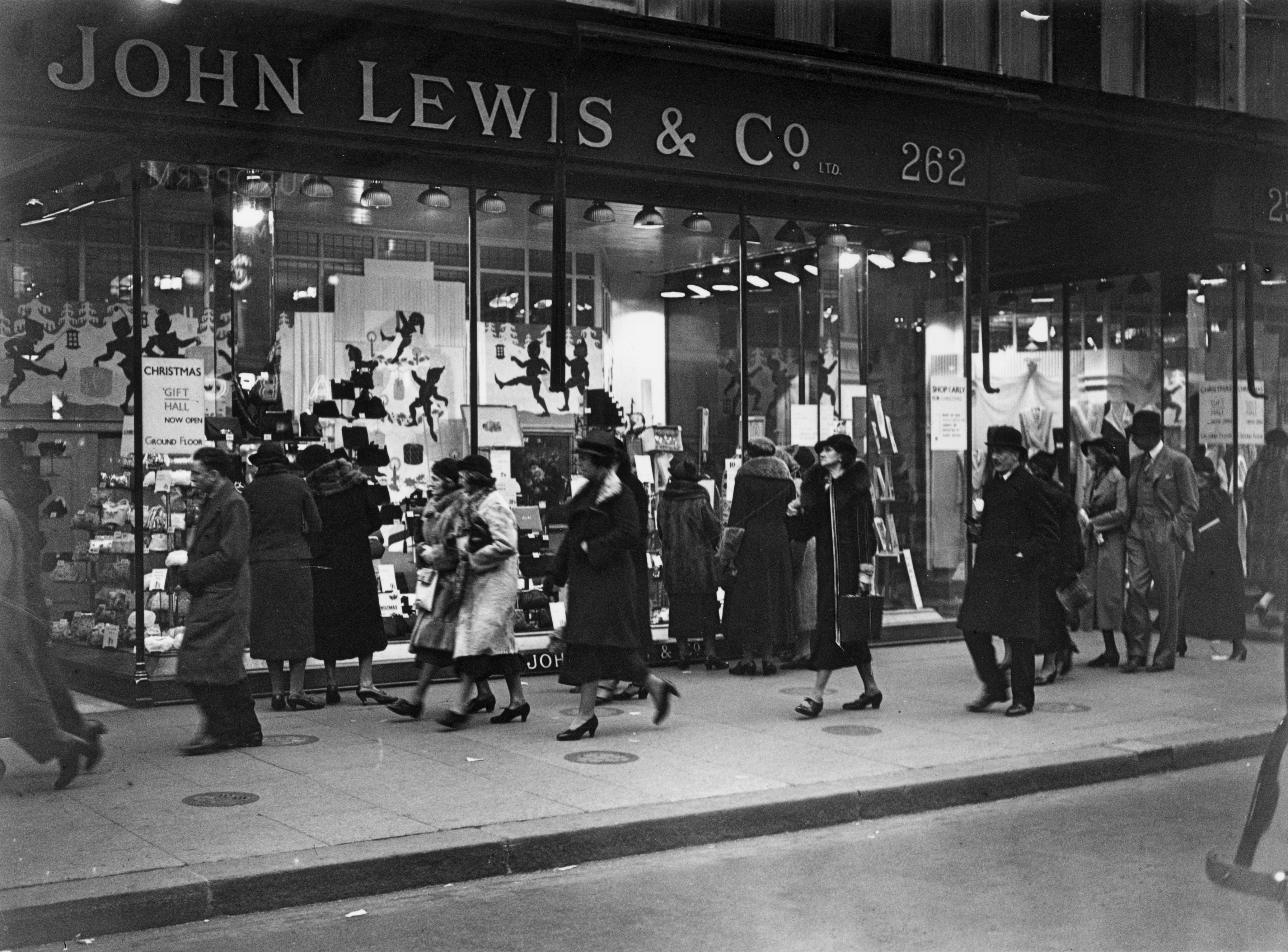

Christmas is rooted in nostalgia, and so are these now less fashionable bricks-and-mortar titans, scenes of generation-spanning seasonal rituals with their window displays, Santa grottos and festive muzak. For much of the year, those still in business may be muted shadows of their once bustling selves, but the opportunity to recapture the buzz of their heyday, however briefly, and remind us of the role they can still play in the retail experience, is there for the taking.

According to a study by Yahoo, 41 per cent of shoppers say they will buy equally online and in store this year, up from 27 per cent in 2020, while research platform Appinio found that a third of 1,000 adults cited in-store displays as the main inspiration for their Christmas shopping.

The heavyweights have responded with various concepts: a cinema at Selfridges in London’s Oxford Street; gin-making workshops and an in-store artisan Christmas market at John Lewis. Yet, as this shift to providing a multipurpose destination gathers pace, a balance needs to be struck. Season-specific “experiences” should coexist with the bread-and-butter service offering, because what will constitute a draw for one part of the customer demographic can adversely affect another.

I recall one Christmas at perhaps the famous department store of all, Harrods, when the decision to make the tea room a shortcut to the children’s Disney-themed event marred my own dining experience. Charging almost £60 for sandwiches and a cuppa can only ever be justified by the supposed elegance of the setting and the sense of occasion this fosters, which here was heavily compromised by the steady trudge of families with excited kids brushing past people’s tables.

The promise of a cinema won’t lure me to a department store; neither will their version of an artisan market, something that is probably best experienced as its own unique entity outdoors, scented by the smell of chestnuts. In the battle to stand out, and to entice a new generation while reconnecting with former customers, stores mustn’t try to be all things; in fact, it would be more welcome if they could simply instil confidence that they have the brands and choice in place, along with some keen offers to merit and reward a visit in person.

A half-decent cafe staffed by a team able to keep a queue moving fast is another bonus – a simple formula the likes of House of Fraser once delivered with ease, before losing its way along with the others.

Indeed, the recent announcement that House of Fraser’s flagship store in Oxford Street is to close next year once again raises uncertainty over the company’s future. For me, this would have been an unthinkable scenario around a decade ago, when my Saturday afternoons played out there in a mecca of pitch-perfect brands and the satisfying buzz of consumerism, pretty much all year round.

The store’s buyers knew their customer – or more accurately, customers (because it appealed to a broad church at the time) – delivering choice, a mix of familiarity and cutting-edge, and a focus on accessible luxe, all conveniently under one roof – a formula that justifiably thrived on the high streets for decades.

Not surprisingly, my brand loyalty climaxed at Christmas, when I’d be particularly susceptible to promotions and the convenience of what became a one-stop emporium for gifts, refuelling at the instore Cafe Nero before tackling another floor – a routine that left me imbued with the festive spirit. When exactly this all stopped, its power faded, and it segued into being a statistic of high-street woes and casualties, I’m not too sure.

What is clear is that the long-term survival of the department store will increasingly be determined by the basics: how well the business understands its customer

Last summer, when I returned to the same branch – one of 41 that remain in the UK – it would have been my first visit in probably six years. Midweek, mid-pandemic, it was never going to be busy, but the difference was still marked. While the layout was broadly unchanged, the vibe was of a nightclub that loses its glamorous artifice when the lights go on at 3 am to reveal spilt drinks and tatty upholstery.

The scope of the premises, once filled with promise and displays, seemed cavernous and clinical, with far less stock and unattended counters. And it was so very quiet – eerily so – that passing another shopper on parallel escalators, as we glided to more floors full of more depleted rails and shelves, almost took me by surprise.

Online has of course disrupted retail, but that alone didn’t kill the department store. The issue was always more complex and nuanced. Like an ageing TV host who has outstayed their welcome, perhaps one of the biggest surprises of the earliest casualties was how long they had lasted in the first place.

My own occasional visits to the likes of BHS and Debenhams, usually to use their toilets, confirmed to me a tired lack of inspiration that didn’t encourage me to spend any more than a penny. In the case of House of Fraser, I didn’t stop going because of a preference for shopping online; “e-tail” can never fully replace or compare to an in-store experience when the latter is on the money.

Notably, my weekly visits were more than simply shopping; they had to be to attract me week in, week out, buying ever more items I didn’t need. The store had in fact become a quasi-leisure space, an environment in which my main hobby of the time could thrive, all because of that elusive and often hard-to-define “right” atmosphere and customer experience.

I think I simply fell out of love with consumerism, the habit of shopping for shopping’s sake, which occupied my time and boosted my mood. I’m not the only one. The shift away from buying material “things” to “experiences”, identified by McKinsey some five years ago, remains a significant trend that poses “a serious impact to the long-term health of supply-chain functionality, and the survival of retail”, according to Wayne Snyder, VP of retail industry at Blue Yonder.

What is clear is that the long-term survival of the department store will increasingly be determined by the basics: how well the business understands its customer and is committed to tailoring and personalising the offering across the portfolio, rather than being a one-size-fits-all, homogenous block. With a 12 per cent rise in bricks-and-mortar trade at John Lewis compared with the same period last year, this upturn in fortunes coincides with a return in focus to the core home-and-electricals offering, and a promise that its remaining branches will be “more reflective of the tastes and interests of local customers”.

A few years ago, I recall writing about an independent department store in Surrey, which was keen to stress its relevance and contemporaneous credentials and how it was very much an antidote to Grace Brothers, the fictional department store of 70s sitcom Are You Being Served? Perhaps at some point that comparison had been drawn, and had unsurprisingly hit a nerve. It wasn’t by any means that kind of an anachronism, but it was a little old-fashioned and quaint, with the same faces manning its counters year in, year out; the toys and haberdashery on the top floor; a school-like canteen; and no online presence.

Yet business was, and still is, booming, with a traditional offering that doesn’t automatically equate to drab and tired, and is resonating with a loyal and local older customer base. One Christmas sale pre-pandemic pulled a crowd that queued down the street in the rain – a reminder that the department store can still find an audience and compete in a fast-evolving retail landscape when it has a strong identity and the confidence to do so on its own terms.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks