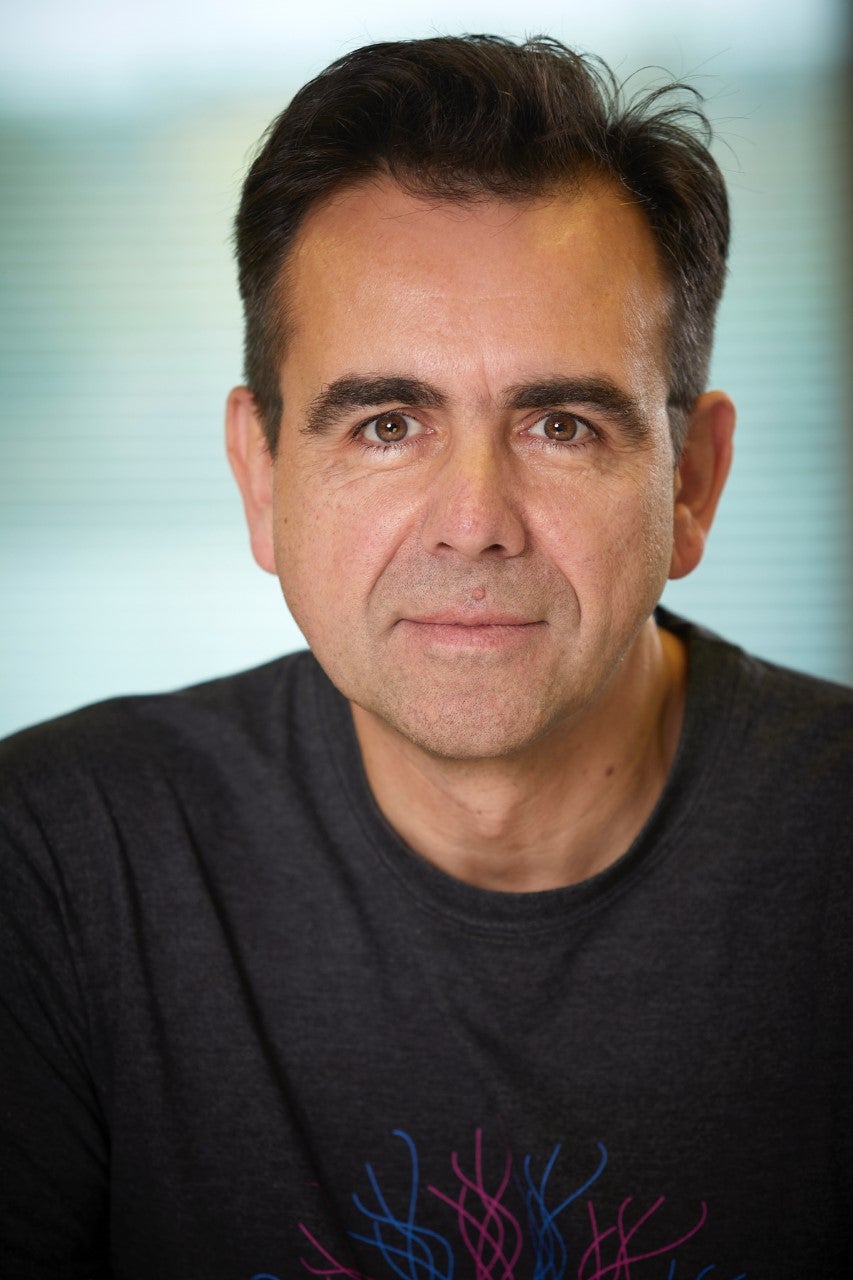

Meet Adam Laurie, one of the UK’s top good-guy hackers

He can use a heart-rate monitor to unlock your car – but don’t worry, he’s on our side, writes Steve Boggan

Once, when I had just arrived at the home of hacker Adam Laurie, he astonished me by using a runner’s heart-rate monitor to unlock my car. On another occasion, bored in a hotel room, he figured out a way to use the TV’s pay-on-demand system to access the hotel’s computer, putting him in control of bookings, room service and customer accounts.

Then there was the time in the Central Lobby of the Palace of Westminster when he demonstrated how the messages, contacts and photographs on the phone of Norman Lamont, former chancellor of the exchequer, could have been stolen as the politician strolled by.

Next – and arguably his coup de grâce – Laurie went on to prove that the microchip in the Home Office’s new national identity card – which was supposed to be the most secure form of ID ever created – could be hacked, cloned and altered even though a rumoured £5bn had been spent on making it impregnable. That was in 2009; the card, which had been a great source of controversy, was quietly scrapped a few months later.

If you’re feeling slightly uncomfortable that such an individual exists and is not simply the creation of an over-imaginative Hollywood screenwriter, then you can relax. Thankfully, Laurie, 59, is one of the good guys, a computing and technology wizard who is on the side of the angels. He spends his days checking the security of IT systems, communication networks and smart gadgets to ensure they are safe before vulnerabilities come to the attention of people who would exploit them, either for financial gain, terrorism or plain old mischief.

Laurie is the lead hardware hacker for IBM’s X-Force Red team, an international group of hackers who are engaged by companies to test the security of their computing systems or products. He did all of the exploits above before joining IBM, but they were instrumental in earning him a reputation as one of the world’s most accomplished – and vital – “white hat” hackers.

In the world of hacking, there are “black hats”, who do bad things, “grey hats”, who sometimes do questionable things but for good reasons, and white hats, who work to keep the rest of us safe.

In the case of Norman Lamont’s phone, white-hatted Laurie stopped before extracting any information, as that would have been illegal. He did it to demonstrate a security flaw in the Bluetooth element of some smartphones that would have allowed crooks, spies or trouble-makers a way to hack into them. After he exposed the problem, the mobile phone industry quickly acted to fix it – as did the manufacturers of the hotel TV system and the car he unlocked with the heart-rate monitor.

“When people hear the word ‘hacker’ they assume it’s a person who has bad intentions or who is out to do damage,” he says. “But without hackers, vulnerabilities and weak security would go unchecked, and consumers – and the devices and websites that individuals and businesses need to thrive – would be much less safe.”

Only recently, Laurie identified a security risk in a 4G telecommunications module – a microchipped device that allows “dumb” products to be connected to the internet, so that they can be monitored and controlled remotely, thereby making them “smart”. The modules were being made in China for Thales, the French electronics multinational, but Laurie found a flaw that meant they could be hacked.

Laurie then went on to change the way music was shared and published by developing the word’s first CD ‘ripping’ software

He told the company and it published a security fix soon afterwards – making safe millions of products and IT systems, including cars, medical devices and aircraft.

Laurie was born in Guildford, Surrey, and later grew up in a flat overlooking Portobello Market in Notting Hill, west London. His mother, Barbara, had a children’s clothes shop there, called Tiger Moth. His father, Peter, was an investigative journalist and editor of Practical Computing, even though at the time there was very little about computers that was “practical”.

“Back then, you switched on a computer and all you got was a black screen with some writing on it – there were no graphics, nothing like Windows,” he says. “My father had some knowledge of electronics, but hardly anyone knew anything about computers. My brother, Ben, and I received some basic computing lessons at school and so when my father ran competitions in which readers were invited to write their own code, we’d check it and report back.

“This meant we also got to try out early computers such as the BBC Micro and the Amstrad. As an investigative journalist, my father always taught us not to simply believe what we saw, but to look under the lid to find out what was going on out of sight. So, inevitably we would always be pulling things apart to see how they worked – and we couldn’t always put them back together again.”

Laurie and Ben, who is now principal engineer at Google Research, went on to learn the programming languages Fortran and Cobol, and while Adam left school at 14, preferring instead to carry on taking things apart and learn more and more about how they worked, Ben went to Cambridge University to study pure mathematics.

A series of business ventures followed during the 1980s and 1990s that were brilliantly ahead of their time.

“In the early days, there was no way for computers to communicate and exchange information between themselves,” says Laurie. “If you wanted to transfer information from one computer to another, you literally had to print it out from computer A and punch it manually into computer B. Then floppy discs came along, but there was no industry standard, so Amstrad’s was different from Apricot, which was different from BBC Micro and so on.

“I founded a company, A L Downloading Services, and developed machinery that got round this problem, and soon it was the largest media transfer business in Europe.”

Cryptography was regarded as a military secret, like a weapon, in the US, so transferring it across borders could have resulted in a prison sentence

Laurie then went on to change the way music was shared and published by developing the word’s first CD ‘ripping’ software, which allowed data – usually in the form of music – to be copied from disc to disc. At first, CD manufacturers said it couldn’t be done, but he proved them wrong.

Next, it would not be an exaggeration to say that Adam and Ben changed the way the internet worked – for the better – forever. In the 1990s, if you had a website, odds are it was run on the Apache web server, a platform that enabled the first high-scale levels of commerce and communication on the web.

“Apache was brilliant but it didn’t allow for secure interactions, and that was holding back people’s trust in doing business on the internet,” says Laurie. This is where brother Ben’s love of mathematics came to the fore.

“Ben’s hobby was cryptography and so we developed a cryptographic layer that could be plugged into Apache that made it completely secure. It was called Apache-SSL, and our plan was to publish it for everyone to use – most things were open source at the time – but there was a problem. Cryptography was regarded as a military secret, like a weapon, in the US, so transferring it across borders could have resulted in a prison sentence.

“We went to the Department of Trade and said ‘What should we do?’ and they said ‘We don’t know. Just get on with it and let’s see what happens’. But no way were we going to do that. Eventually, the Cambridge computer laboratory offered to publish the cryptographic layer and said they would use their reputation and legal resources to defend the action if needed. But then Oxford came along and said they’d publish, too, then other universities and computer labs published it.

“Eventually, the US had to accept that cryptography was a tool that should be used to make everyone more secure. It even reached a point where people were going through US Customs wearing T-shirts with our crypto algorithm written on the front!”

Since joining IBM three years ago, Laurie has seen his role as being at the vanguard of making secure “internet of things” devices and systems.

“Everything in your home is becoming connected to the internet and to everything else to make them smart, to enable them to perform in ways that will make your life more convenient,” he says. “Cities, cars, trains, every aspect of our lives will be connected – but that kind of connectivity comes with security risks, and so that’s going to keep us very busy in the coming years.”

And if that makes us all safer, it’s comforting to know we’re in such good hands.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments