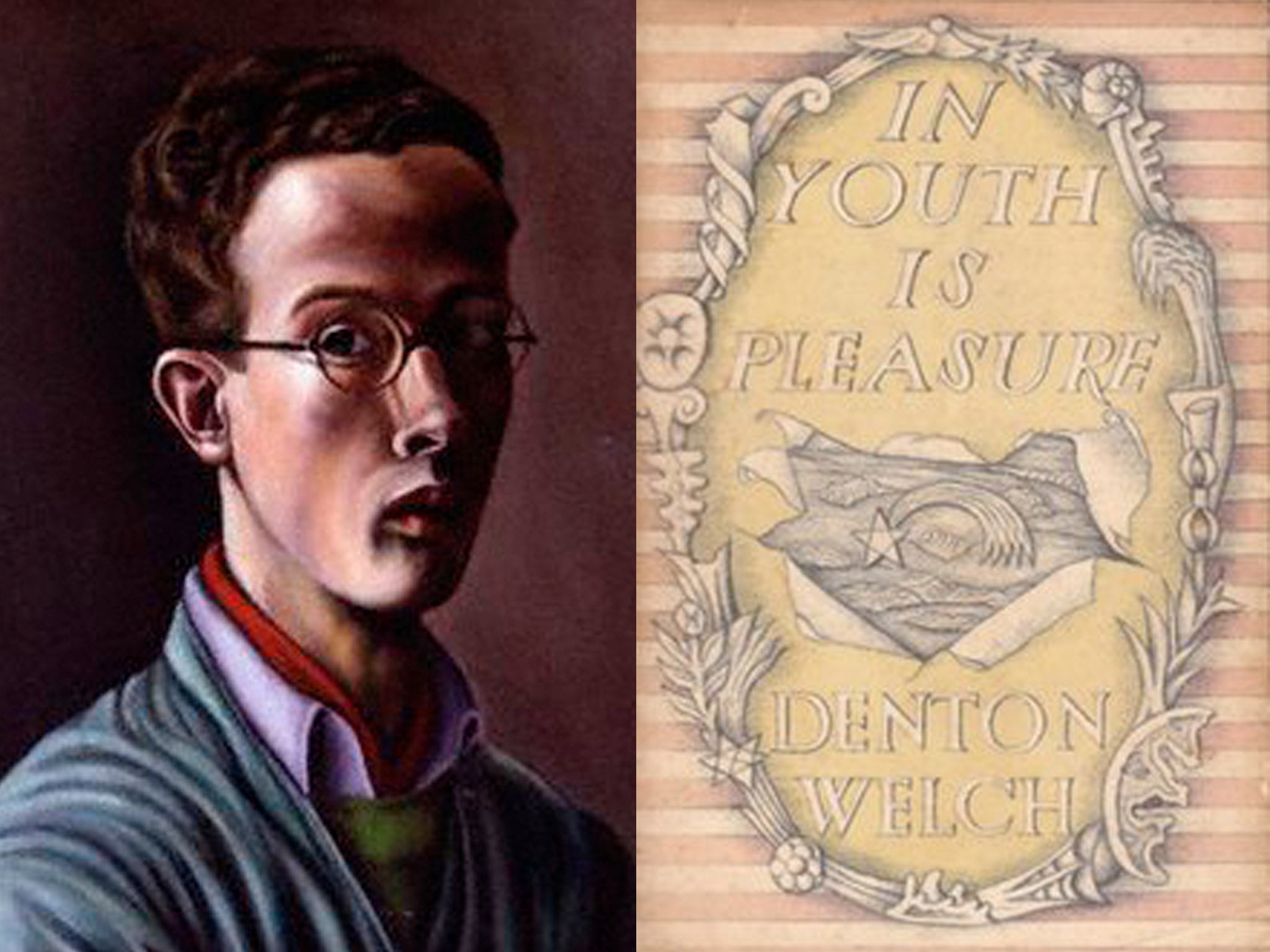

Book of a lifetime: In Youth is Pleasure by Denton Welch

From The Independent archive: ‘In Youth is Pleasure’ by Denton Welch

I was a typical teenager. I loved Egon Schiele and The Smiths. At school break, I’d run down to the river to skim flat pebbles and drink Whiskey Mac with classmates. Our blue and gold uniforms sparkled in the sun, and I’d retreat to the shade to read Denton Welch’s In Youth is Pleasure. It begins “One summer, several years before the war began, a young boy of fifteen was staying with his father and two elder brothers at a hotel near the Thames in Surrey.”

This is a threshold time, before the devastation of war, before the devastation of adulthood. Orvil Pym is the boy, a rough-haired strange boy who takes us on a heightened, sensual journey. There is little plot, simply an artful third person that allows Orvil a direct line, and makes the ordinary astonishing. For Orvil, Peach Melba – the tinned variety – is “like a celluloid cupid doll’s behind” and the “diminutive tombstones” of a pet cemetery are like “a giant’s dominoes”.

Orvil is a boy obsessed: with trinkets, with food, with physical improvement (to sweat he shuts himself in the bottom drawer of a dressing chest, wrapped in a quilt). He is also obsessed with death, with tearing his clothes off and running through the Surrey countryside, with the right way of doing things, with memories of his dead mother (she chases him with a hairbrush and hits him with the spiked side). Orvil is a voyeur and as he leads us through grottos and abandoned cottages, we take in every drop of feverish detail.

When the scarlet canoe with a schoolteacher and two lusty lads appear, another obsession comes into focus. These golden men “glinted like silk” and Orvil watches them through the long grass. The two lads beg the teacher to read them a passage from Jane Eyre. “Sir, please!” they cry. The teacher calls them “young bastards”, then reads out the scene where Jane meets Rochester in the lane. Orvil notices how “one of the boys tried to rub his hands up and down while he held them tightly imprisoned between his taut thighs. It was a strange, unconscious, very excited movement.”

Orvil and the teacher have two more encounters, both deliciously odd, certainly sadomasochistic, but furrowed with this same black humour. Orvil Pym may not know how to live, but he certainly knows how to relish and embrace the lushness of life (for instance, when he dots his face and body with stolen Sang de Rose lipstick and jumps about his hotel room).

Welch was an invalid, knocked from his bike aged 20. There is autobiography here, as in all of Welch’s work: the dead mother, the absent father, his sexuality, his hatred of boarding school. Yet it is Orvil’s vibrant energy that allows this book to bubble. The fact that Welch could, at times, only manage a few sentences a day makes this energy, this beautifully odd way of translating the world, all the more spectacular.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks