Book of a lifetime: Ulysses by James Joyce

From The Independent archive: Joseph O’Connor on the great modernist masterpiece

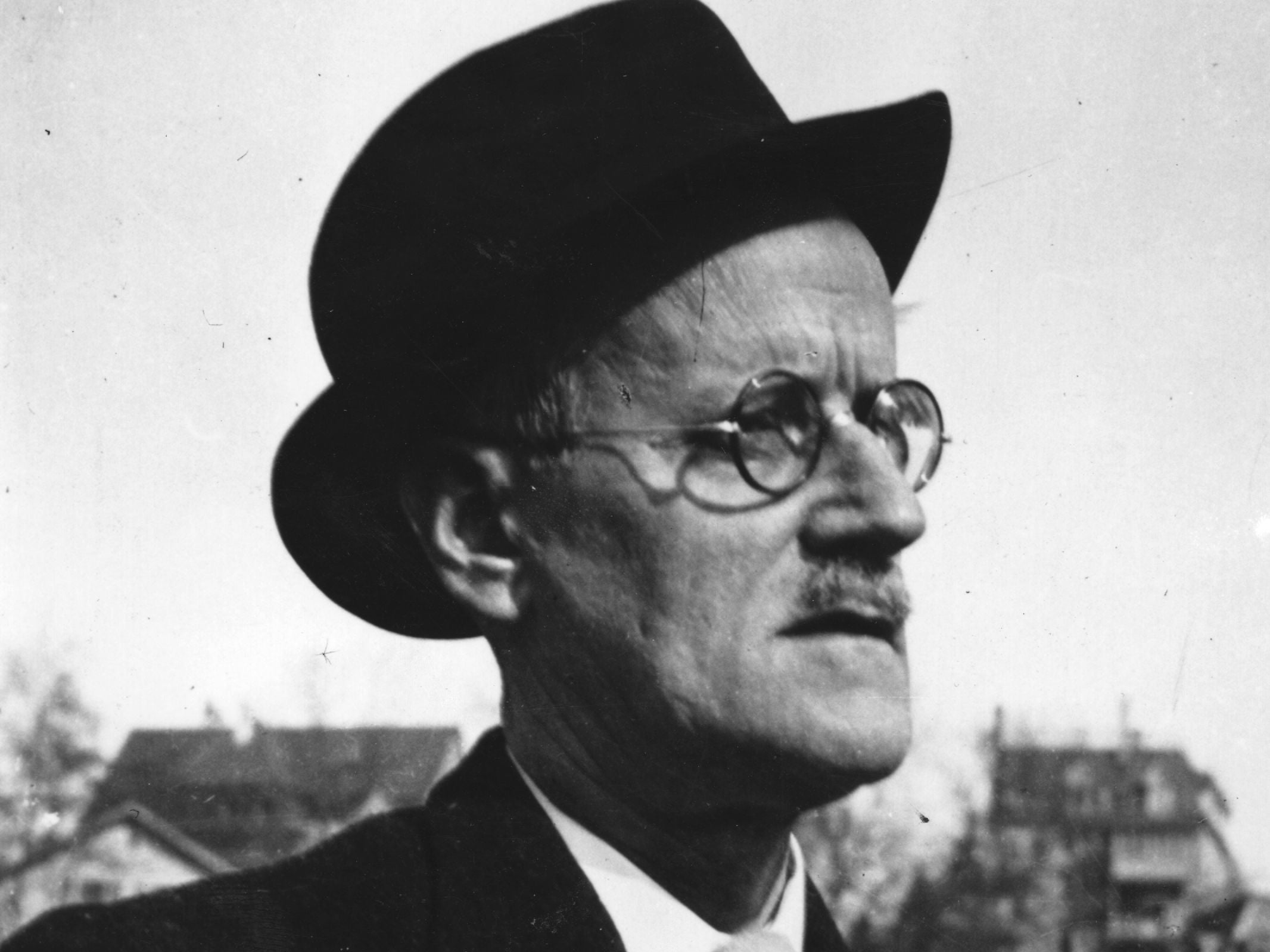

He is always there, the genius who spun the meanderings of a handful of fictitious nobodies into the greatest novel in the history of the form. The city of James Joyce’s Ulysses is long dead now – it was already disappearing when the book was published in 1922 – but somehow the ghost of Joyce still haunts the margins of world literature like a wanderer yearning to come home.

The lost Dublin he immortalised is a shadowplace of contrasts, a provincial Edwardian backwater. It has elegance and pitiless squalor; the desolation of a scandalised diva reduced to beggary. Chandeliers illuminate her mansions, candles glow in chapels; red lights flicker in the brothel doorways. Joyce said his hometown had “a faint odour of corruption”. But few novelists have written more beautifully about any city. And nobody has ever depicted with such scrupulous precision what it is to be a native of a colony.

If ever there was a novel that is truly about everything, it is this wonderful, infuriating book. It contains passages of unearthly beauty, sequences funnier than any stand-up comedian, sentences so graceful that you stand in the sunshine of that summer day, transported by the communion of language. It is virtual reality, a century before the internet. It is Fellini before Fellini, and Scorsese before Scorsese. And it is flawed, in the way every great work of art is flawed, from Beethoven’s symphonies to the Rolling Stones’ Exile on Main Street.

This is fiction with friction, jaggedness, juice, and those of us who have made our way to those astounding final pages have rubbed our eyes on a summit where the view raises gasps. Give Ulysses a chance and its pleasures are spellbinding. Yes, it contains passages that are trying. Few of us could truly say we love every sequence in the book, as we mightn’t love every track on a treasured album. Those tracks should be skipped. Ulysses shouldn’t be overly respected. Don’t regard it as a sacred text. It’s an adventure in pleasure. Without its challenges, it would be a skinny and mean-hearted novel.

At its core is a simple phrase: the halting voice of Leopold Bloom, saying: “Love – I mean the opposite of hatred.” This is a book about a city’s rain, the secrets of its citizens, about seeing that we are connected to them, and they to us. It’s a story about how to live, about eating and drinking and sex, the confetti-storms of memory in which most lives are lived, about the joys that suddenly burst from life’s darknesses and sadnesses like berries from some lost album of wildflowers. It’s about how to be young and how to approach middle age.

“I was so much older then,” sings Bob Dylan of his youth. “I’m younger than that now.” The same is true of Bloom, most lovable of all Joyce’s characters: a man who talks to cats, sympathetic and humane. In the end it’s a love song to a troubled, broken world, a story about glancing up at the sky on a night in June and glimpsing “the heaventree of stars hung with humid nightblue fruit”.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments