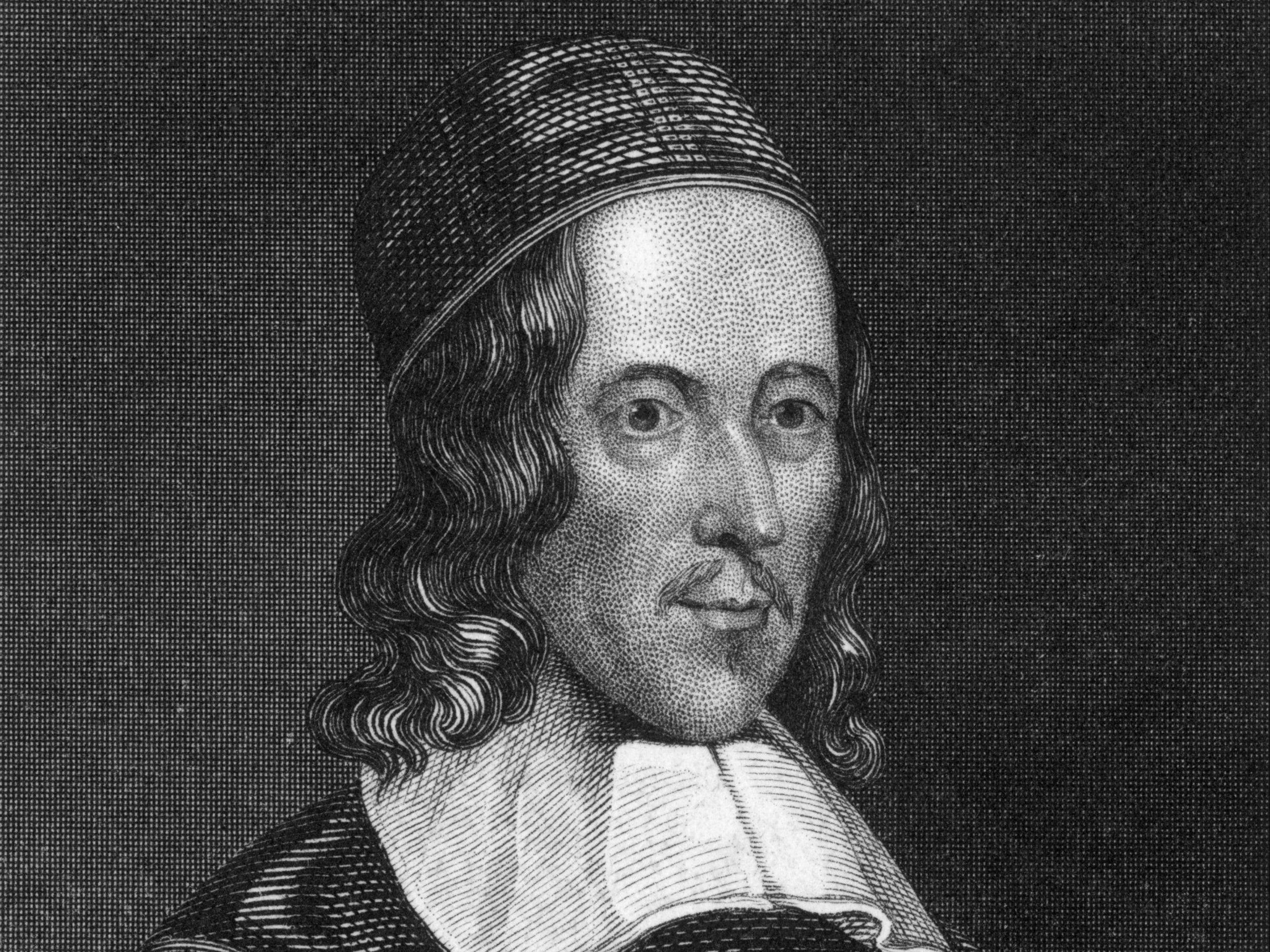

Book of a lifetime: Poems of George Herbert

From The Independent archive: Paul Bailey on the enduring humanity and curiosity in the verse of the great metaphysical poet

There are two books I cannot contemplate living without. The first is Dickens’s Great Expectations and the second the Poems of George Herbert. I have taken my little Oxford World’s Classics edition of the latter, bought in 1957, everywhere I have ever been. It has sustained, delighted and moved me in the heat of Australia and the ferocious cold of the American northwest. Herbert is the most sweet-tempered of the great Metaphysical poets and perhaps the most subtle too. Consider these lines from “Giddinesse”:

“Surely if each one saw another’s heart /There would be no commerce /No sale or bargain passe; all would disperse /And live apart.”

That might be the plot, in miniature, of many a novel, good and bad, for the Reverend George Herbert is no intellectual slouch. He thinks – you can almost hear him thinking – about what he is saying so memorably, so beautifully. He argues with himself and, occasionally, with his God:

“Ah, my deare God, though I am clean forgot / Let me not love Thee, if I love Thee not.”

What I love in Herbert’s poetry is its sense of the luminosity of the ordinary. He writes of men and women, of food, of birds and trees and flowers, of each and every human thing. If you cannot believe, as he did, that the world has been touched by a divine hand, that shouldn’t make you deaf to the verbal music with which he gives his belief expression. I know of no lovelier poem in the language than “The Flower”, in which he rejoices in the passing of grief:

“And now in age I bud again / After so many deaths I live and write / I once more smell the dew and rain / And relish versing...”

It was in 1937, the year of my birth, that Simone Weil, the most widely read and educated of mystics, discovered Herbert’s “Love”, with its marvellous opening words:

“Love bade me welcome: yet my soul drew back / Guiltie of dust and sinne / But quick ey’d love, observing me grow slack / From my first entrance in / Drew nearer to me, sweetly questioning / If I lacked anything...”

“I learnt it by heart,” she wrote to her spiritual adviser, Father Perrin. “Often, at the culminating point of a violent headache, I make myself say it over, concentrating all my attention upon it and clinging with all my soul to the tenderness it enshrines. I used to think I was merely reciting it as a beautiful poem, but without my knowing it the recitation had the virtue of a prayer.”

This transcendental masterpiece ends with the line “So I did sit and eat”, when the unworthy guest accepts Love’s invitation to break bread at the table. Simone Weil accepted that invitation, too.

George Herbert has been my constant friend and travelling companion for more than 50 years. He will be staying with me until the end.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments