Why did the great plays of Arthur Miller make for such bad films?

While film versions of plays by Tennessee Williams and Edward Albee did roaring trade at the box office, Miller’s work stuttered. But 60 years on, ‘The Misfits’ stands as the purest and least compromised of any of the films in which Miller was involved, says Geoffrey Macnab

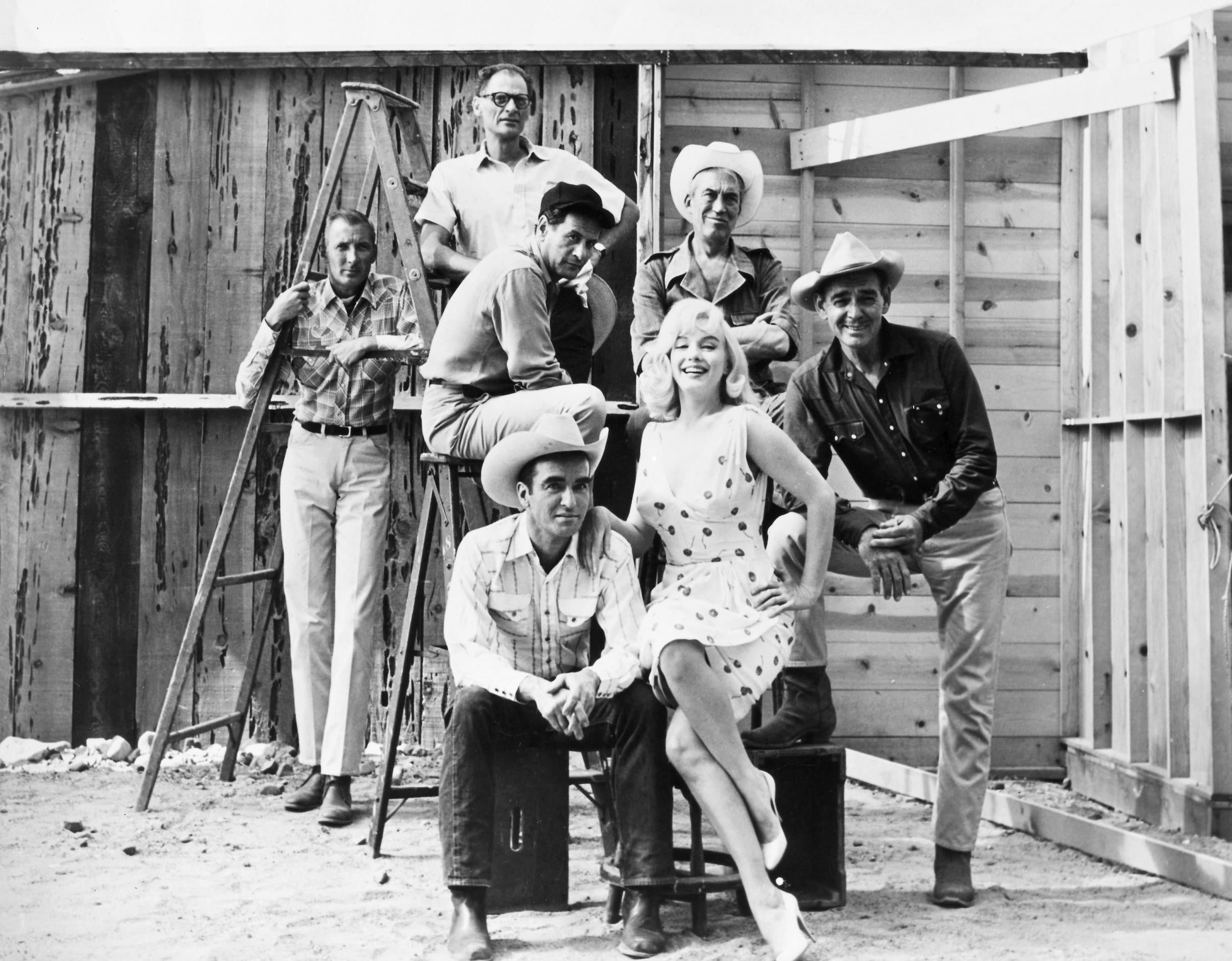

He was one of the greatest playwrights of his era but Arthur Miller (1915-2005) had a very patchy record when it came to movies. His plays packed theatres but their screen adaptations rarely did more than the most modest business. Nor did his original film projects fare much better. Miller assembled three already legendary stars, his then-wife Marilyn Monroe, Clark Gable and Montgomery Clift, for The Misfits (1961) and yet the film barely covered its costs on its initial release.

In 1996, when the British stage director Nicholas Hytner made a movie of The Crucible from a screenplay by Miller himself, the play, first performed in 1953, was already acknowledged as a cast-iron classic of American theatre. It was on school syllabuses everywhere. Whenever there is persecution or paranoia anywhere, whether during the anti-communist hysteria of the McCarthy era when Miller wrote the piece or in the first days of the Trump presidency, Miller’s dramatised account of the Salem witch trials is still always cited as the perfect allegory. Hytner’s film starred Daniel Day-Lewis and Winona Ryder, both at the peak of their popularity, but still contrived to misfire with the public.

While big-screen spin-offs from Miller’s work stuttered, film versions of plays by Tennessee Williams and Edward Albee or of novels by Ernest Hemingway and John Steinbeck often did roaring trade at the box office. Of the major American writers of the last century, Miller had the lowest strike rate in cinema.

A glib explanation for Miller’s long run of movie duds is that he was an anti-Hollywood figure. He was a New York Jewish intellectual who scorned the superficiality of the studio system. He had had close Communist Party links during the 1940s that led to his blacklisting. His plays, most notably Death of a Salesman (1949), were often about failure and were too downbeat to attract a mass cinema-going audience, regardless of their Pulitzer Prizes and Tony awards. This, though, doesn’t really explain Miller’s struggles to engage with cinema or his ambivalence about the medium.

There is an intriguing anecdote early in Miller’s autobiography, Timebends, which reveals that the writer’s self-made, illiterate father very nearly became a Hollywood big shot. In 1915, the year Miller was born, William Fox, who worked in the fur industry, asked Miller’s father for a loan of $50,000 to help set up a movie studio in California. His father rejected the offer and then went on to lose all his own money in the Depression.

“It would have been inconceivable to him [the father] that afternoon, as he told Fox the bad news, that in not so many years he would be finding it hard to scratch up the price of a ticket to a Twentieth Century Fox movie,” Miller wrote on how he “narrowly missed an entirely different life as the son of a Hollywood mogul”.

That was Miller’s first reversal in the film business, at the very start of his life, and there would be many more.

“It’s a very mysterious business. It’s very difficult to generalise about the movies. It has a mystical effect on you finally. I can see why people devote their whole lives to fiddling with this [medium],” the playwright, then at the end of his career, told producer/director Gail Levin when interviewed for her documentary Making The Misfits (2001).

Miller was a famously uncompromising figure who didn’t want movie adaptations to take liberties with his plays. In the early 1940s, he went to Hollywood to work on an early draft of the screenplay of The Story of GI Joe, based on the wartime reporting of the celebrated newspaper columnist and star reporter Ernie Pyle. True to his principles, he promptly resigned when another writer was hired to work alongside him. His biographer Christopher Bigsby reports that, in 1947, he turned down a deal to write a film to be directed by Alfred Hitchcock. By then, he had seen at first hand “just how low the writer’s status was in movies”.

Some fine directors, among them Laslo Benedek, Sidney Lumet, Volker Schlöndorff, John Huston and Karel Reisz, have made films based on Miller’s work. Often, though, they have been far too reverential towards the playwright, far too aware that they are dealing with the sacred words of one of the towering figures of American drama.

“What I found irritating about Miller – with all the respect I have for him – is that he belongs to that category of artist who becomes a prisoner of his own pretensions,” Lumet, who had a rare misfire with his 1962 screen version of Miller’s A View from the Bridge, told one interviewer. “The article that he published before the premiere of his play in which he compared it to a Greek tragedy attests to that … you are hurting your play when you try to make it pass for Euripides.”

The films were often unlucky with their casting. Fredric March was a superb actor who had played the fading Hollywood star, lost in alcohol and self-pity, in the 1937 version of A Star is Born, and who had given a performance of immense pathos and subtlety as one of the troubled war veterans in The Best Years of Our Lives (1946). On the face of it, he was the perfect choice to play Willy Loman, the doomed American everyman, in the film version of Death of a Salesman (1951). The original 1949 stage production, directed by Elia Kazan, had already been a triumph.

Miller had sold the rights to producer Stanley Kramer. As he later wrote in Timebends, his only participation in the film, directed by Benedek, “was to complain that the screenplay had managed to chop off almost every climax of the play as though with a lawnmower, leaving a flatness that was baffling”.

March had been first choice for the stage role but had turned it down. Miller was appalled by his performance in the screen adaptation. March portrays Loman as a man unhinged, hurtling fast towards the reefs. It may have been bravura acting but it “obliterated” the play’s social context, turning it into a story about an individual’s mental illness, rather than a broader social drama about the American dream gone disastrously wrong. On stage, the hulking Lee J Cobb had played Willy with “a touch of human grandeur” and with “solid humanity”, as one reviewer put it. He had been much more sympathetic and likeable than March’s Willy and had tugged at audiences’ emotions as a result.

Whatever reservations Miller already had about Hollywood, they were exacerbated when Columbia asked him to “issue an anti-communist statement” in advance of the film’s release. The studio then tried to add a short film to the Death of a Salesman programme, explaining that Willy was a woeful exception and that selling was “a fine profession with limitless spiritual compensations as well as financial ones”.

Miller hadn’t thought much either of the 1948 film version of his earlier play All My Sons, which starred Edward G Robinson as a manufacturer accused of shipping defective parts to the air force that led to the deaths of 21 pilots. He later told Bigsby it was “a laughable melodrama that ought to have been burned” and that all his speeches had been rewritten, with their “subtleties sand-blasted away”.

Even so, the writer returned to LA in the early 1950s.

In Timebends, Miller writes about the “contradictory mixture of certain scents” Hollywood evoked for him: “a sexual damp … raw gasoline and lipstick perfume; swimming pool chlorine and the scentless smell of rhododendron and oleander”. He was excited to be there with Kazan, trying to get his screenplay The Hook, dealing with corruption and murder in the New York docks, produced by Columbia. He first met his future wife and muse, Monroe, during the trip, on the set of the comedy, As Young as You Feel, in which she had a small part. “When we shook hands the shock of her body’s motion sped through me, a sensation at odds with her sadness amid all this glamour and technology and the busy confusion of a new shot being set up.”

As before, the trip wasn’t a success. Miller’s brand of gritty, social realist drama rankled with the studios. Miller was told by Columbia boss Harry Cohn that if he didn’t make the villains communists, “the movie would be an anti-American act close to treason”. He reacted by withdrawing his script. It must have been galling for him when, a few years later, Kazan made the similarly themed On the Waterfront (1954) without him. By then, though, Kazan had betrayed his former colleagues in the Communist Party by naming names to the House Un-American Activities Committee, thereby putting an extreme strain on their friendship.

If Kazan had directed Hollywood versions of Miller’s plays and screenplays, they would surely have turned out very much better than they did in the hands of other filmmakers. The various movies spun off from Miller’s plays and screenplays have rarely had the intensity, focus and energy that Kazan brought to his projects as a matter of course.

Not that all Miller adaptations were failures. Dustin Hoffman, who had played the role on Broadway the year before, makes an exceptional Willy Loman in Schlöndorff’s made-for-TV 1985 version of Death of a Salesman. He has a nervous charm and vulnerability that you don’t find in March’s far angrier performance. John Malkovich is equally striking as his son, Biff, the former high school football star who has turned into a feckless drifter.

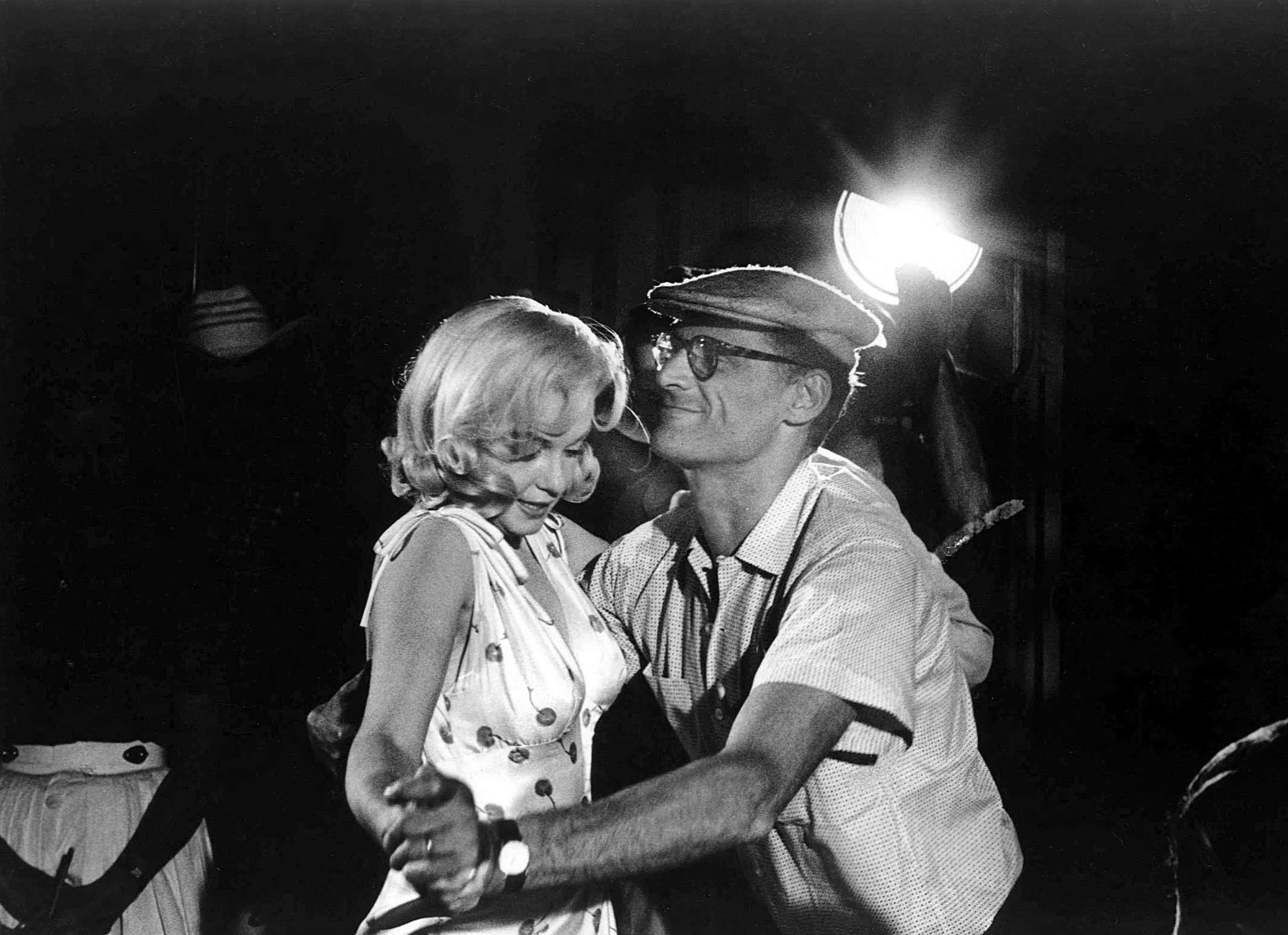

John Huston’s The Misfits (1961), about rodeo riders, ageing cowboys and divorcees adrift in Reno or chasing wild mustangs in the Nevada deserts and mountains, was a famously chequered production. It went over budget and over schedule. Miller had intended it as a valentine to Monroe but, during shooting, their marriage imploded. Her behaviour was erratic and her time-keeping infuriating. This, though, is a heartrending movie in which, against the odds, Gable, Monroe and Clift, alongside a youthful Eli Wallach, give their rawest and most tender performances. It combines an old Hollywood feel with the best of Method acting. It also has an obvious added poignance because Gable and Monroe never completed another film after it.

Ironically, Miller felt that Huston wasn’t making The Misfits cinematic enough. “What intrigued me somewhat about life in Nevada was that the people were so little and that the landscape was so enormous. They were practically little dots … they were like specks of dust,” Miller told Gail Levin. He wanted Huston to give the film an epic quality. Instead, the director did close-up after close-up, concentrating on the inner emotions of his tormented protagonists. Nonetheless, the credits are very revealing. For once, Miller’s name appears as big as those of his stars. He originated the project, found the producer and hired Huston.

At the time of The Misfits’ release, audiences were flummoxed. It wasn’t a typical Monroe or Gable vehicle and nor was it a conventional western. Sixty years on, it stands as the purest and least compromised of any of the films in which Miller was involved.

‘The Misfits’ is available to stream on the MGM platform via Amazon

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments