Germany prepares to bid farewell to ‘Mutti’ as Angela Merkel eyes her political exit

Merkel’s leadership has spanned 16 years, and she has won praise for her calm handling of multiple crises. But critics point to the vacuum she now leaves behind her, writes Erik Kirschbaum

Angela Merkel, who made a career of outfoxing powerful male rivals as she led Germany through a 16-year-long period of prosperity, will be leaving office after next month’s parliamentary elections as the country’s first post-war chancellor to retire on her own volition.

Merkel’s calm leadership, longevity in office and towering reputation abroad may have helped to burnish Germany’s image overseas, yet her failure to groom a successor and her efforts to push her conservative Christian Democrats into the political centre have weakened her party at home – possibly dooming the success-spoiled conservatives to the opposition benches after September’s election.

The unflappable trained scientist, who earned a PhD in quantum chemistry in formerly Communist East Germany, has been the epitome of tranquility while steering the EU and the continent’s most important country through a series of major crises – from the 2008 global financial crisis to the Greek debt and Eurozone crises to the 2015 refugee crisis and the United Kingdom’s tortuous “Brexit”. Merkel, who turned 67 last month, also showed plenty of spine in standing up firmly yet politely to former US President Donald Trump in four years of withering attacks on Germany, the EU and NATO.

It won’t help to try to bang your head through the wall because the wall will always win

“She’s been called the ‘leader of the free world’ and I’d argue that she’s had a very successful run,” said Julius van der Laar, an international political strategist in Berlin. “What Germans will remember about her a few years from now is that it was a pretty turbulent time and she navigated Germany and herself quite deftly through all these various crises. She’s been a savvy political operator and remarkable in her ability to read public opinion as it shifts.”

Merkel has always been a quick study with an uncanny ability to size up her counterparts or audience in any room without giving anything away. There are no records of any angry outbursts and she rarely showed any emotion – a serenity Germans came to adore, electing her in four successive elections after she defeated incumbent Social Democrat Gerhard Schroeder in 2005. She was affectionately known as ‘Mutti’, which translates literally as ‘Mummy’ - a calm and reassuring presence, not given to extremes. She only fired one minister, for selfish insubordination, during her four terms and 55 ministers. One of her favorite explanations for the unflustered approach was: “It won’t help to try to bang your head through the wall because the wall will always win.”

She helped guide the EU through a period of significant upheaval. She took office just as the EU was doubling in size from 15 members to 28 and later faced challenges such as the rise of international terrorism, a massive influx of refugees, the Eurozone debt crisis and the rise of far-right parties in a number of countries, including her own. She was also a bulwark of liberal Western values who seldom wavered when it came to take a firm stance whether it was against Russian President Vladimir Putin’s growing aggression and China’s spreading influence.

“Merkel’s method was crisis management – keep the dialogue open under all circumstances,” said Jackson Janes, a senior fellow at the German Marshall Fund in Washington DC. “Don’t let the pots boil over if possible. She led the negotiations and sanctions with Putin in dealing with Ukraine, she slowly moved Germany in the direction of economic support for European partners, helped deal with Brexit from becoming a contagious disease in the EU and she opened gates to refugees. She also manage to deal with four very different Presidents in Washington.”

Merkel’s method was crisis management – keep the dialogue open under all circumstances. Don’t let the pots boil over if possible

Mastering the uniquely German style of “leading from behind” in Europe in a continent still wary of overtly strong German leadership 75 years after the end of World War II, Merkel has been viewed as the quintessential safe pair of hands. Her steadfast commitment to budget discipline and fiscal austerity was essential for her to stay in power at home but made her a villain in countries such as Greece, Italy and Spain. The southern European countries struggled to meet the high standards Germany and other northern countries placed upon the European Central Bank and EU institutions.

It was the profligate spending in the past in the EU’s so-called “peripheral countries” that triggered a debt crisis and what ultimately turned into a broader Eurozone currency crisis. Her success in helping to keep the single currency together as it teetered on the brink of collapse in 2015 was regarded as one of her great accomplishments even though it cost her support among conservative voters and party allies at home -- who would have preferred to see Greece and other heavily indebted countries such as Italy leave. She portrayed the crisis as an existential threat to European unity: “If the Euro fails, Europe will also fail.”

Merkel won applause for her leadership after Russian annexed Crimea in 2014 and pro-Russia rebels seized the southeastern regions of Donetsk and Luhansk. She led a united front in the West against Putin while maintaining an important dialogue with the Russian President. They both speak each other’s languages and used those skills to facilitate their exchanges. Merkel studied Russian in her youth and spent time living in Moscow.

Putin once nearly succeeded in rattling Merkel, who has a deep fear of dogs since, having been bitten as a child. Possibly aware of that, Putin invited his large black Labrador Konni into a meeting with Merkel at his summer residence in Sochi in 2007. “The dog doesn’t bother you, does she?” Putin asked, either feigning ignorance of Merkel’s discomfort as the dog sniffed her or genuinely unaware. “She’s a friendly dog and I’m sure she’ll behave herself.” Merkel tried to crack a joke in Russian for Putin about dogs not wanting to eat journalists. He later apologized, saying he did not know of her phobia. Merkel later said: “I believe the Russian president was fully aware that I wasn’t thrilled to meet his dog. He brought him anyhow.”

Perhaps more than anything else, Merkel will be remembered for her bold decision in 2015 – political rivals called it reckless -- to open the country’s borders to more than 1.5 million refugees flooding north into Europe from Syria, Afghanistan and the Middle East. It was an act of humanitarianism that changed the political landscape and life in Germany and the EU. Historians said it might well have contributed to the forces that drove the UK out of the EU with its ‘Brexit’ vote less than a year later.

Merkel’s historic decision was at first cheered by millions of Germans who greeted the arriving refugees at train stations with food supplies, blankets and even toys for children. The move was also initially applauded and supported by many across Europe.

Yet Merkel’s altruistic open-door policies soon caused deep divisions not only in her country, but also in her conservative Christian Democrat party and in the EU as well with many nations, especially in eastern Europe, opposed to taking in a share of the refugees. The far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) party in Germany, which was created in 2014 as an anti-euro party opposed to Merkel’s rescue efforts for Greece, and populist movements elsewhere across Europe were given a new lease on life by the 2015 decision to suspend the usual border controls and allow in the large numbers of refugees. The AfD has been siphoning away crucial support on the far right from Merkel’s party for the last seven years.

“Germany is a strong country,” Merkel said in Berlin, which became known as her famous “Wir schaffen das” (“We can handle this”) speech. “The motivation with which we should approach these things has to be: We’ve handled so much. We can handle this.” The criticism of her decision to open the borders continued to unfold as up to 10,000 refugees per day streamed into the country.

The tensions that followed caused a sharp erosion of support for Merkel’s conservative party in elections across the country. Her conservatives won more than 35% in her first victory in 2005 but fell to 32% in 2017. They are now polling at a meagre 22% ahead of the September 26 elections, where a three-party centre-left coalition of Greens, Social Democrats and Free Democrats is now viewed as a distinctly viable outcome.

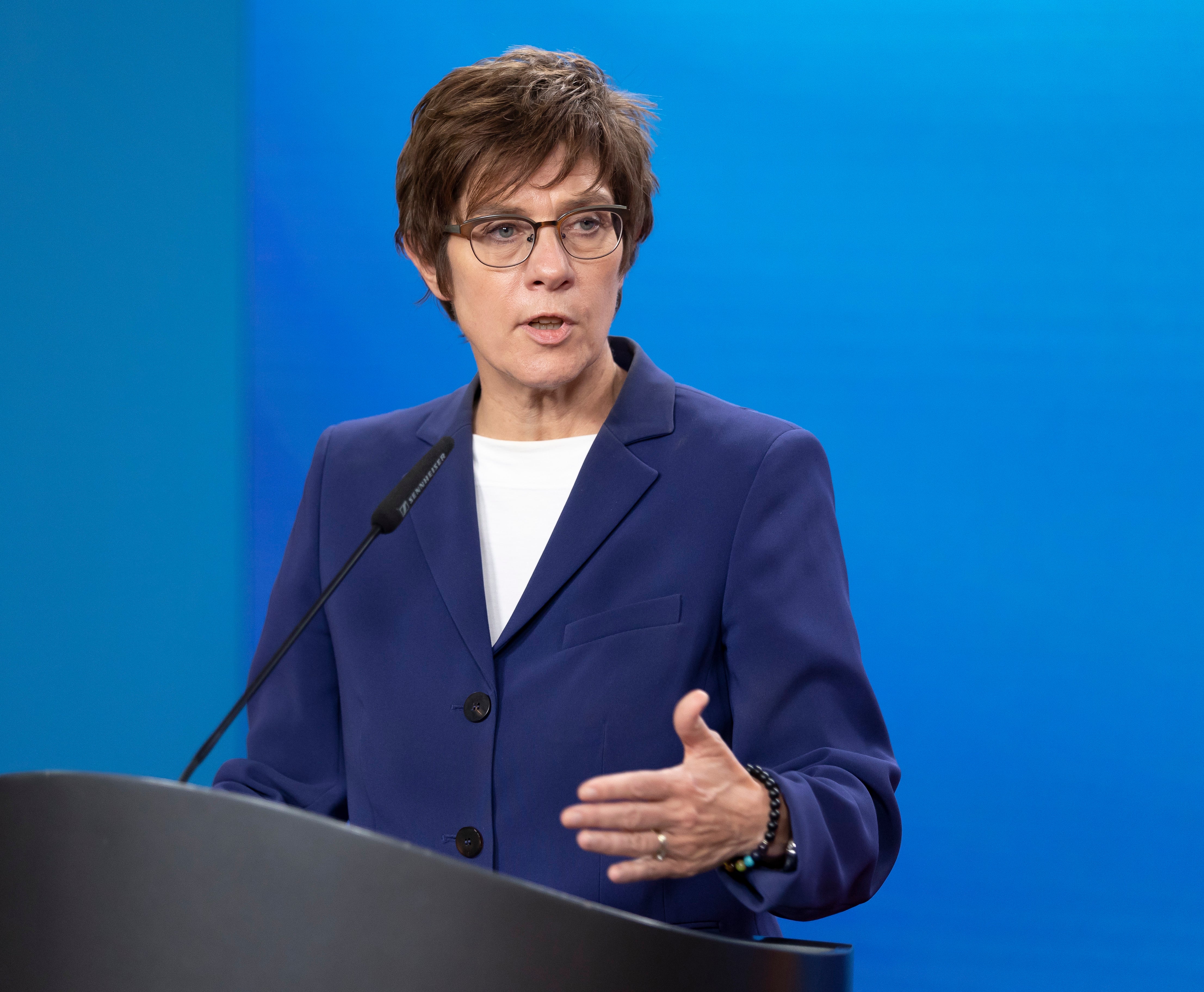

Exacerbating the conservatives’ woes is their weak and unpopular candidate, Armin Laschet. The Chancellor adroitly beat back a dozen male rivals over the years, politically eliminating a long list of would-be successors but leaving the party without an heir apparent. She had backed another woman to succeed her, Defence Minister Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer, but she resigned as party chair last year after a series of blunders.

Despite her continued popularity, Merkel has not campaigned on Laschet’s behalf and so far has just one scheduled appearance with the state premier of North Rhine-Westphalia.

“She’s an incredibly effective power player who kept a tight control on her party,” said van der Laar, who worked on Obama’s campaigns in the United States. “She sent anyone close to becoming dangerous to her to the EU in Brussels or took them down a notch or two in Germany.

“But it’s now become clear that there’s no one on the bench to step in for her. That’s going to be a problem for her party.” this, too, will be part of her legacy.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments