‘I left the KGB with £500, a 1977 Volvo and the rose-tinted belief that anyone could succeed in business’

He grew up in a shared flat in Moscow and went on to own a major Russian bank – but success did not always make Alexander Lebedev popular. Here, in the first of three extracts from his new biography, he recalls his early life, and how he warned Gorbachev of the economic troubles that would bring down the USSR

I was born on 16 December 1959 in Moscow, in the maternity hospital on Proletarskaya Street. We lived in a communal apartment on Avtozavodskaya (Automotive Factory Street) and a little later, when I was three, the family’s fortunes improved to the extent that we moved to a small 36-square-metre apartment of our own. At that time my parents could hardly have imagined how their younger son’s career would develop.

My father, Yevgeny Nikolaevich, had a doctorate in engineering and was a professor in the education department of the Bauman Higher Technical College in Moscow (now the Moscow State Technical University). There he forged elite engineers for the land of triumphant socialism. My mother, Maria Sergeyevna, taught history to the next generation of Soviet people and, later, the language of the ‘probable adversary’, namely, English. They had no idea what the First Directorate of the KGB of the USSR might be, and for them millions of dollars were to be found only in the novels of John Galsworthy and Theodore Dreiser.

I owe my secondary (and very middling) education to School No 17, which offered ‘intensive study of the English language’. It was what was known in those days as a ‘specialised school’. I had the privilege of attending a representative specialised school at the height of the Soviet Era of Stagnation. We had some fine teachers of, for example, English and literature: reading and studying Shakespeare and Robert Burns in the original was seen as nothing out of the ordinary. Many years later, already in adult life, I was able on a couple of occasions to surprise British friends by reciting Hamlet’s monologue.

I studied well enough, but consistently got bad marks for conduct, which meant my parents were regularly called in to the school to hear expressions of concern. These were not infrequently about tricks I got up to with Sasha Mamut, with whom I had been friends since first grade. He was eventually moved to a different class: from B to C.

In arts subjects my marks were excellent, but in physics, chemistry and mathematics, less so. I blame the teachers. I did not warm to them, and they left me with a life-long aversion to their subjects, even though the shelves in our apartment housed dozens of books my father had written and which contained wall-to-wall maths as applicable to optical engineering (and not without military applications). For me, though, that was terra incognita. The situation was quite different with my mother: English, history, literature... To this day I enjoy nothing more than reading Gibbon on the Roman Empire or Sebag-Montefiore on the Romanovs. I think my father was a little envious.

As was typically the lot of a professional family in the USSR, we lived modestly but were reasonably well provided for by the standards of the time. I was taken aback years later by a photo posted on Instagram by my already adult son, Evgeny. It showed the refrigerator in his home in London with at least 60 bottles of different kinds of vodka. He boasts an excellent wine cellar of over 100,000 bottles! Such a thing was beyond imagining in the two-room apartment I shared with my parents and brother.

Even had I come into the possession of such a quantity of alcohol, two dozen friends would have helped me despatch it in a couple of days. (‘Head on over, lads, my folks are away. The flet is ours!’) And afterwards Mamut and I would have taken the bottles to the collection point and wrangled with the fat women there over every supposedly disqualifying chip on the necks of the bottles.

I emerged from secondary school with a commendable certificate. There was no blat (parental string-pulling) involved, even though my mother taught at the prestigious Institute of International Relations (IIR) and was a member of its Communist Party committee. Before applying for a place I had a year’s tutoring, and even gave up water polo, which I had been playing since a child. I was beginning to have trouble with my eyesight. I couldn’t see well and there were no contact lenses.

The institute’s principal was also called Lebedev. He was no relation to my mother but pretended he was. There was serious jiggery-pokery in the USSR, at the highest level

In those days blat was fairly common, especially at IIR. My cohort included many progeny of members of the Politburo: Andrey Brezhnev, for instance, grandson of the general secretary of the Party, or Ilkham Aliev, whose father was a member of the Politburo and future president of Azerbaijan. Nowadays Ilkham is president of the republic himself.

Vladimir Potanin, today the CEO of Norilsk Nickel, was in the year below mine. I remember a great fuss when my mother, who was very honest, failed Brezhnev in English. The other lecturers began avoiding her, giving her a wide berth when they passed her. About a month later she was walking along the corridor when she met Andrey. ‘Maria Sergeyevna!’ he exclaimed. ‘Guess what? I’ve already managed a “very good”!’

The institute’s principal was also called Lebedev. He was no relation to my mother but pretended he was. Brezhnev’s wife had phoned to request that Andrey not be expelled but moved from Maria Sergeyevna’s group to a different one. The end result was that the principal ended up on good terms with the general secretary’s family. There was serious jiggery-pokery in the USSR, at the highest level.

Twice a week I went to the food shop to stand in five or six queues. There were separate ones for making a purchase and paying for it. At times the shop would run out of eggs or milk, cheese or sausage, and at best there were only a couple of varieties. You could choose between Soviet cheese or Russian cheese. Eggs were always called ‘Extra’, sausage was always ‘Gourmet’. Often at home I would take a mouldy 13-kopek loaf from the cooking pot in which the bread was kept, cut off the crust, pour water over it and put it in the oven. I would retrieve half a month-old pack of pelmeni dumplings from the freezer and douse them with mayonnaise. Spongey, sprouting potatoes, eggs, frozen pollock or cod – such was pretty much my diet for 20 years or so.

How I came to be recruited by Yasenevo into the foreign intelligence agency remains something of a mystery. I had been planning to write a thesis at the Academy of Sciences’ Institute of Economics of the World Socialist System and go into academic research. I had even chosen my dissertation topic: Problems of Debt and the Challenges of Globalisation. In my final years at IIR, however, headhunters from the KGB’s First Directorate began taking an interest in me.

This was despite the fact that, in the first place, I shunned all work for the Young Communist League, the Party, and any other social commitments. Secondly, I was sceptical about Marxism-Leninism, read Solzhenitsyn and Shalamov (discreetly), and told political jokes. In short, I showed every sign of developing into a dissident. As a result of these proclivities, I blotted my copybook at the very beginning of my career as a spy.

Nevertheless, ideological shortcomings apart, my professional qualifications fitted the role rather well. I had English, I had quite respectable Spanish, I was married and had a child. Was the world of intelligence in those years secretly some anti-Soviet ‘Union of the Sword and Ploughshare’? After all, the people who worked in it were well educated and knew the reality of how foreigners lived. They could not be taken in by Soviet propaganda, because they were the ones who concocted it.

My fourth year was a year abroad in Libya. Translators were needed from the higher education institutions that were considered most trustworthy. The contract was for six months and the pay was what you might have expected if you were a ‘grown-up’ working for a foreign trade organisation. It was everything a Soviet citizen could hope for!

How I came to be recruited into the foreign intelligence agency remains something of a mystery. I showed every sign of developing into a dissident – I blotted my copybook at the very beginning of my career as a spy

The USSR had signed a contract with the Libyan Jamahiriya to build a nuclear research facility with a 10-megawatt light water reactor in Tajura, a 40-minute drive from Tripoli. Its purpose was to train future specialists to work at a nuclear power plant Gaddafi was proposing to build on the Gulf of Sidra (Great Sirte). The would-be local specialists turned out, however, to be a bunch of ne’er-do-wells from wealthy families who had no desire to study and only wanted to move to America or the United Kingdom at the first opportunity.

In June 1981, shortly before we arrived, Israel carried out Operation Babylon in Iraq, bombing an Osirak class nuclear reactor near Baghdad, which the French had sold to Saddam Hussein. The Israeli prime minister, Menachem Begin, had publicly threatened to bomb Tajura as well, so the situation was tense. There were a lot of Libyan soldiers posted at the facility, very young men (at times they seemed to be just boys with enormous boots and assault rifles). We had anti-aircraft defences. In the event of an air raid, we were to hide in a shelter that had survived since the Second World War, a legacy of General-Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, commander of the Third Reich’s Afrika Korps.

Drinking alcohol was prohibited in Tajura and the law was quite severely enforced: for a booze-up you could find yourself in a zindan punishment pit. We broke the law regardless, and distilled moonshine. One time everyone got poisoned and some people ended up in hospital, but our superiors turned a blind eye. Political unreliability was a different matter. On one occasion I told a joke at a party:

Okay, there’s this big gala event in the Kremlin Palace of Congresses to celebrate the anniversary of the October Revolution. Everybody’s there, the Party and government leaders, the Heroes of Labour, the Young Pioneers, the astronauts. It’s being compèred by none other than People’s Artist of the RSFSR, Joseph Kobzon. He announces, ‘And now we invite to the stage the legendary Sidor Kuzmich, who saw Lenin. Twice.’

The hall goes silent. A decrepit old man clambers up on to the stage. Kobzon asks him, ‘Tell us, Sidor Kuzmich, how did you come to meet the leader of the world proletariat?’

‘Er, let me think,’ Sidor Kuzmich wheezes. ‘1917 it was, in Razliv (that’s near Petrograd). So, I’m in our village bathhouse. I’ve got one foot in this basin full of hot water and the other in a basin full of cold water. Really good birch-twig switch, and all the people around are just so nice! Only thing missing is the vodka: ban on drinking alcohol there was. Suddenly in comes this nasty little bare chap, really small, bald too. In he comes to the bathhouse, doesn’t even close the door behind him. Walks straight over to me. “Look here, geezer,” he says, “how about you let me have one of those basins?” So I says to him, “How about you get stuffed!” That’s how I saw Lenin for the first time.’

Everyone in the hall is shocked. Murmuring. Kobzon does his best to smooth over the embarrassment. ‘Comrades! Let us not misunderstand. Sidor Kuzmich is getting on in years. His memory is no longer what it was. Sidor Kuzmich! Tell us about how you met Lenin the second time.’

‘Ah, yes!’ the old man replies. ‘The second time it was at the Mikhelson factory. I’m standing there, grinding some widget on the lathe. Suddenly the door to the shop floor opens and in comes a whole crowd of people, must’ve been 20 of them, all in those leather coats, with revolvers and pistols, and there with them is that bald chap I saw in the bathhouse. I’m standing there, shaking like a leaf. Anyway, he walks straight over to me. He comes over and I’ve got all these people surrounding me. The little bald chap is looking out from behind this tall fellow, had a goatee beard – Dzerzhinsky that was, I think – anyway, he looks out and says, “Look here, aren’t you that geezer who wouldn’t let me have a basin in Razliv in 1917?” I’m thinking, “If I admit it, they’ll shoot me on the spot. If I say it wasn’t me, they’ll shoot me anyway.” So I says to him, “How about you get stuffed!” Yes, that’s how I saw Lenin the second time.’

Everyone laughed. My friend Alexey told the joke to his dad, who worked in the Second Directorate of Counter-intelligence and was in charge of the section controlling entry to and exit from the USSR. His dad told the story to another person and they laughed too, but someone said: ‘What kind of people are you recruiting there to work in intelligence?’ To make matters worse, my mother had been on a couple of delegations to the United States and was corresponding with Americans. The upshot was that after IIR I didn’t get the attestation I was expecting and was packed off as an ordinary Joe to the translation bureau.

I drudged there for three years or so. My colleagues – and about 15 from our course went into intelligence – were getting paid four times my salary, and in the evenings on the bus driving us back from First Directorate headquarters in Yasenevo, they would pat me condescendingly on the shoulder and say, ‘Never mind, old man, it’ll work out in the end!’ Oddly enough, translation matters too, even if it is uncreative. I put in the hours, took on extra work, burned the midnight oil, and the fruit of my labours was a certificate of commendation from the director of the KGB, Vladimir Kryuchkov. Also a knowledge of Portuguese and Italian.

An opinion was forming at the highest political level of the USSR that we were getting something wrong about Western capitalism. It had been decaying for many decades now, but not collapsing. The authorities’ response was to engage in resolute positive thinking

At just this time ‘an opinion’ was forming at the highest political level in the USSR – in the mind of Yury Andropov, I believe – that there was something we were not getting right about the decay of Western capitalism. It had been decaying for many decades now, but showed no sign of collapsing. In fact, things appeared to be moving in the opposite direction: the USSR’s problems as it competed with the West seemed to be piling up. The authorities’ response was to engage in resolute positive thinking with the aim of persuading themselves nothing could be wrong, because theoretically nothing should be.

Andropov, the general secretary of the Central Committee, started asking questions. He summoned the most trusted advisers with responsibility for the struggle against capitalism and said: ‘You keep repeating that capitalism is in the third stage of its general crisis, when it is certain to collapse, but I have the impression things may not be quite so straightforward. Can you explain to me why the USSR’s foreign debt is increasing and we know nothing about it? And why grain prices are so high and oil prices so low?

‘Why are we having to buy grain from the States and Canada? Why are foreign exchange rates so unfavourable to us? Why are we lagging behind so drastically in technology? And why are our financial arrangements with the countries of the socialist camp so much to our disadvantage?’ The comrades either did not know the answers, or thought it better not to give them.’

The questions were readdressed to the Academy of Sciences, where the academicians put their tails between their legs, well aware that they would get no thanks for telling the truth and that, in any case, these were classified matters they were not supposed to think about. Andropov turned to the intelligence community, which also proved clueless. In the end someone had the idea of setting up a small department in the information analysis directorate of the KGB, which had been processing economic data.

This was why I had been headhunted from the Academy of Sciences, then sent into exile as a translator, but was now being set to work. At some point this junior employee had come to the attention of Nikolai Leonov, the head of the directorate. My translations of financial topics landed on his desk and he was impressed by my understanding of them. ‘So, you are an economist? We need economists for the department.’ With a time lag of three years, I got my attestation.

The task of an analyst in the directorate was to sort through tons of information discovered and supplied by agents in the field, to throw out the rubbish and compose short notes from what was of value. This was sent on up to the chiefs of the intelligence community and from them, if they felt something specific needed to be reported, to the country’s leaders.

As they liked to tell us, ‘You need to write so that even an idiot can understand it.’ The length of this report for idiots could be as little as half a page, although it was usually permissible for it to extend to two or three pages. Without neglecting my work at the coalface, I graduated from the Red Banner Institute of the KGB and was awarded my captain’s epaulettes.

I was sent to the London embassy, where my specialism was financial and economic information. Comrades making the first easy money felt an urge to visit the financial capital of the world, where I looked after them

Leonid Shebarshin, the head of the First Directorate, approved my candidacy to work in a residency. As was traditional, I was found a job in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA), where I worked with genuine commitment for almost a year. The people at Smolensky Square did not at first sniff out who I was: a sociable chap who enjoyed a chinwag with the rest of the staff? But then, after three months or so, someone put it around that I was from the ‘deep-drilling section’.

One fine day I arrived at work to find everyone stony-faced and searching their memories: ‘God Almighty, have I blabbed to him about anything?’ They did not know whether I was working for intelligence or counter-intelligence. I had clearly been overenthusiastic in my penetration of the MFA, but with time everything settled down.

After my stint at the MFA I was sent, by now a diplomat, as an attaché to the London embassy. The days of the Soviet Empire were coming to a close and perestroika was in full spate. The country was changing before our eyes. My family lived where I had been posted, but each year we flew back to Moscow for a month’s leave (our tickets were paid for). In the evenings we watched Vzglyad (‘Look’) on television, and read newspapers that had begun telling the truth.

My specialisation was financial and economic information, but I made useful unofficial contacts in the City, meeting many senior managers of banks and companies. In the Soviet Union a new class of entrepreneurs was being born. Comrades making the first easy money felt an urge to visit the financial capital of the world and, as the member of the embassy responsible for economic matters, I looked after them.

Some turned up at our address in Kensington Palace Gardens, some I met at Heathrow, others I drove around in my little Ford, and some even stayed at my house. I met Mikhail Prokhorov, who was flaunting a wad of £50 banknotes beyond the imagining of a humble Soviet official; Vladimir Potanin; the late Vladimir Vinogradov, proprietor of Inkombank; Sergey Rodionov and Vitaliy Malkin, the owners of Imperial and Russian Credit, the first commercial banks; Oleg Boyko, who traded in computers and engaged in currency operations.

According to my calculations, the USSR was heading for a default on its foreign debt and the situation had become critical. I was allowed to meet Gorbachev at two o’clock in the morning to tell him

My school friend Alexander Mamut was there in the commercial whirlpool and, as a lawyer, was servicing almost everyone: he flew in to open accounts in London for Mikhail Khodorkovsky. With my salary of a few hundred pounds a month it was an eye-opener to see how the New Russians partied at night in the clubs and restaurants.

In April 1989, while Margaret Thatcher was still prime minister, Mikhail Gorbachev, the general secretary of the Central Committee, came to London on a second official visit (the first had been in 1984 when he was still only a member of the Politburo). According to my calculations, the USSR was heading for a default on its foreign debt and the situation had become critical. The embassy had its own internal politics, and I was allowed to meet Gorbachev only at two o’clock in the morning. Leonid Zamyatin, Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary, had no wish to report my very own scientific discovery, although he believed it was entirely correct. ‘You go. You tell him,’ Zamyatin said.

The general secretary was sitting at the ambassador’s desk, in a secure space where there were jammers to frustrate attempts at bugging. Twenty people were in the room and the air was so thick with cigarette smoke you could see nothing. The ambassador introduced me: ‘This, Mikhail Sergeyevich, is one of our near neighbours [an ominous silence …], but he has something to report.’ Zamyatin thus prepared himself a path for a hasty retreat, making it clear that if my report did not go down well, it was nothing to do with him.

I told Gorbachev it would soon be impossible to service our national debt, explaining how and why. Someone raised objections and I was, as it were, booed off the stage. Nobody could believe such a thing was possible. The Soviet colossus seemed to be standing firmly on its feet. Just a year and a half later, however, Gorbachev was to send the following telegram to John Major, the newly elected prime minister of the United Kingdom:

Dear John,

I am writing to you as coordinator of the ‘Big Seven’ with an urgent request for financial assistance.

Despite all the measures we have taken, the currency situation is in danger of collapsing. By the middle of November, the deficit of liquid currency resources needed to fulfil the USSR’s foreign debt liabilities will be about $320 million, and by the end of the present year may reach 3.6 billion. All the underlying calculations were submitted to experts of the ‘Group of Seven’ in Moscow on 27–28 October.

In order to avoid matters taking an undesirable turn, John, I am asking you to make available liquid resources in any form acceptable to you in the amount of $1.5 billion, including $320 million before the middle of November.

Mikhail Gorbachev, 2 November 1991

The default of the USSR, about which I had warned, followed shortly after that. It occurred on 28 November 1991, when Vneshekonombank (the Bank for Foreign Economic Affairs) ceased operations and declared itself de facto bankrupt. A week later, in Belovezhskaya Pushcha, the leaders of Russia, Ukraine and Byelorussia announced the dissolution of the Soviet Union, and on 25 December Gorbachev appeared on television to make a farewell address as president of the USSR to his fellow citizens.

How to make a billion while retaining your integrity

In early 1992, by which time I was a lieutenant colonel, I returned from my ‘extended foreign business trip’. More precisely, I did not return: I was recalled. A high-ranking ‘open’ diplomat, who had close links with our service, harboured unfounded suspicions about my relations with his wife and reported that I had lost some ridiculous unclassified document. I was referred for investigation. He had given me the document himself, together with permission to mention it at an open conference, where I had read it out.

Before my departure, I spent two days composing a lengthy telegram of 15 pages about how our economic intelligence system should be structured, which areas it should focus on, how it should be subdivided, what questions it should address, how its staff should be trained, and so forth. This was in response to a request. As I later learned, my note found its way to the desk of the newly appointed director of the Foreign Intelligence Agency, Yevgeny Primakov. Not involved in the internal politics of the service, he asked for me to be found and, just three days after my return, I was in his office.

Primakov knew me a little from the past. I had been friends with his daughter and visited them at home. ‘Hello, Sasha! As you see I am reading your telegram.’ And indeed, there was my telegram in front of him, covered in scribbles, pasted with stickers, and annotated with different coloured marker pens. ‘We discussed this telegram yesterday for two hours. But why are you looking so miserable?’ I explained I was suspected of something totally absurd.

Primakov discussed my suggestions for an hour, at the end of which he phoned the head of my directorate. ‘Have you got some misunderstanding there about Lebedev? Kindly trust him. He is an intelligent and disciplined officer.’ He gave me the option of either being promoted to the rank of general to run the foreign economic intelligence service, or return to London.

‘You know, Yevgeny Maximovich,’ I said. ‘Your intervention will put me in a very awkward situation. If some lieutenant colonel gets made a general and placed in charge of a new directorate, he will be cold-shouldered and you will not be able to protect me. I will put in another three months or so, then leave the service and go into business.’

Primakov responded: ‘As you will.’

I got my things together and left the service. At that moment in time I possessed a hard-earned £500 and a 1977 Volvo with left-hand drive. The capital city of my native land had turned into one big flea market and presented a dismal aspect, but I viewed life through rose-tinted spectacles. I had no experience of living and surviving under capitalism with a Soviet face and believed anyone could succeed in business. The reality was to fall short of that.

The firm I set up with Andrey Kostin, the counsellor at the London embassy, was called the Russian Investment Finance Company. We took on everything that came our way, piling, as was considered normal at the dawn of capitalism in Russia, into one thing after another: property, consultancy, trade … on the whole, unsuccessfully.

We bought a wagonload of women’s shoes from South Korea, only to find they were all size 34 and for the same foot. Another time we bought a batch of televisions that did not work

For example, we bought a wagonload of women’s shoes from South Korea, only to find they were all size 34 and for the same foot. Another time we bought a batch of televisions that did not work. We planned to supply barbed wire from Russian detention facilities to UN troops in Mogadishu, but it turned out that Soviet barbed wire was not up to modern standards. We did nevertheless turn a modest annual profit, a five-figure dollar sum.

The Russian Investment Finance Company then rented an office from the Interior Ministry’s medical section in the basement of a half-ruined mansion at No 23, Petrovka, which had been designed in the late 18th century by Matvey Kazakov. It was just across the street from the capital’s police headquarters. We sank all our meagre profits of around $40,000 into refurbishing the mansion.

While the renovation was going on, we were stuck in the basement with no toilet and no heating. During the winter we heated the place with a heat gun. When the fashionable renovation was finally complete and we moved into a wing, tattooed gangsters turned up and said: ‘The cops have sent us round to get you out.’ They were followed by the deputy interior minister, an individual with the eloquent surname of Strashko, Mr Fierce, who personally supervised the eviction. Needless to say, they paid us not a kopek.

That dark period lasted several years. Eventually I felt I could take no more, and even Freud’s doctrine about spiritual anguish paving the way to happiness did not help. I sat on the sofa and stared fixedly at one point, acutely aware of my own uselessness, not wanting to do anything, unless perhaps to disappear.

‘You don’t want to do anything? Not even to smoke?’ Until that moment I had been unable to give up smoking, and got through a couple of packs of cigarettes a day. That state of not wanting to do anything was enough to enable me to kick the evil habit, and to this day I try to use my lapses into depression (which still recur) to mobilise hidden reserves and engage in self-improvement.

Finally, in 1995 Lady Luck smiled on me. We were acting as consultants for Sergey Rodionov at Imperial Bank. I had advised many people to buy up sovereign debt in foreign markets, but no one knew what kind of beast that was, and no one believed it was possible to make good money from it. Rodionov, however, became interested in a deal I proposed to buy Brady bonds, named after the US Treasury secretary, Nicholas Brady. These were the national debts of Mexico, Venezuela, Nigeria and Poland, and were highly volatile.

$300k

The amount needed to purchase National Reserve Bank

On my advice, Imperial bought $7 million worth of these securities and in six months made $3 million on them. (Subsequently they tried to play the game without me and got in a right pickle.) We received a highly acceptable commission of about half a million bucks. What were we to do with what seemed to us an unbelievable fee? We spent some of it on a yacht trip in Greece, and knocked together a couple of offshore companies. Bankers were making the best money at that time, and I decided to spend $300,000 on one of Oleg Boyko’s numerous dwarf ‘banklets’. It had the imposing name of National Reserve Bank, although in reality it was no more than a licence with no actual assets or liabilities.

How we transformed this shell in the course of two years into one of the leading banks of the Russian Federation remains a mystery to many people. They keep looking for ‘Communist Party gold’ and ‘KGB money’

How this shell was transformed in the course of two years into one of the leading banks of the Russian Federation remains a mystery to many people. They keep looking for ‘Communist Party gold’ and ‘KGB money’, where in fact there is no mystery. Everything is completely transparent. At that time the person with most influence in the Russian economy was not the first president of the Russian Federation, Boris Yeltsin, or even prime minister Chernomyrdin, but a modest 34-year-old deputy minister of finance called Andrey Vavilov, who carried drafts of the budget to the State Duma in a string shopping bag. He was the person managing the state’s finances, controlling the nation’s entire banking system, pulling the strings and allocating the deposits of the Ministry of Finance to private banks.

Vavilov kept these balances in Khodorkovsky’s Menatep bank, Boyko’s National Credit, Smolensky’s Stolichny [Metropolitan] Savings Bank and a dozen other major banks. That was where all the money circulated. Today’s all-powerful state-owned banks, Sberbank (Savings Bank) and VTB (Bank for Foreign Trade) were not yet playing any role, and the Central Bank just sat very quietly and did not interfere.

A secret commission, chaired by Vavilov, reported to the Ministry of Foreign Trade, and all the intelligence agencies with an interest in foreign debt issues were represented on it. This was the moment when a Russian secondary market for foreign exchange bonds was being formed. These were, in the first place, the government’s domestic foreign exchange bonds, issued by the Ministry of Finance in late 1993 against the liabilities of the bankrupt Vneshekonombank (Bank for Foreign Economic Affairs) of the USSR.

They were also known as Taiga bonds or Vebovki (VeeBees). These bonds were on the balance sheets of foreign trade associations, and they did not know what to do with them. In the second place there were credit claims by Russia and its foreign trade associations against other countries and companies.

I proposed a scheme. Suppose a thousand Western companies owed us debts totalling billions of dollars. They might simply find someone to bribe and have them written off in return for a kickback. My proposal was to set up a consortium of banks that would buy up these debts at a 50 per cent discount. I persuaded Imperial Bank, National Credit, Capital Savings Bank and Menatep that this was a good idea, and thereby brought to my own bank some very solid clients among the state-owned foreign trade associations. I had money from the Ministry of Finance on the books of National Reserve Bank.

Our next success was with Gazprom, around which the greater part of business at that time was literally ‘circling’. Many future oligarchs spent days and nights in the reception room of Rem Vyakhirev, chairman of the board of the monopoly. However, unlike those who wanted to embezzle the nation’s assets, or at least grab themselves as large a slice of the national cake as possible, I saw a real problem Gazprom was facing and came up with a solution.

Ukraine owed Russia a huge debt for gas. The now independent republic was diverting ‘blue gold’ from the Soviet export pipeline for its own consumption, and settling the bill not with cash, which it did not have, but with promissory notes, so-called gazpromovki.

In 1995, 10 series of a total of 280,000 bonds were issued with a nominal value of $1.4 billion. I suggested the Ukrainians should convert these notes into sovereign debt. That is, Ukraine should issue bonds, place them on the stock exchange in Brussels where they would be bought in the stock market, and Gazprom would get its money.

The Ukrainians did not issue them in electronic form, though, but printed them as bits of paper, which they deposited in the basement of the National Credit Bank branch in Kiev. What good, you might well ask, were they going to do there? It was something out of the 19th century! ‘Well, pal,’ someone told me, ‘that’s a lot of paper you got issued …’

I promised to think of something, and a day later was back in Vyakhirev’s office, to find him and his deputy Vyacheslav Sheremet waiting. I made them an offer.

‘We’re going to give you a benchmark price. National Reserve Bank buys these bonds for 75 per cent of the nominal value in a bilateral arrangement, and you invest that amount in me as capital. No cash has to be exchanged: all that is needed is the recording of a transaction between banks.’

The upshot was that the omnipotent gas monopoly became a shareholder of National Reserve Bank without having to pay a kopek.

Someone who is today an oligarch, and whom I often met at that time in the venerable reception room on Nametkin Street, commented as I was leaving, ‘Our financial Mozart!’

Part two next Sunday

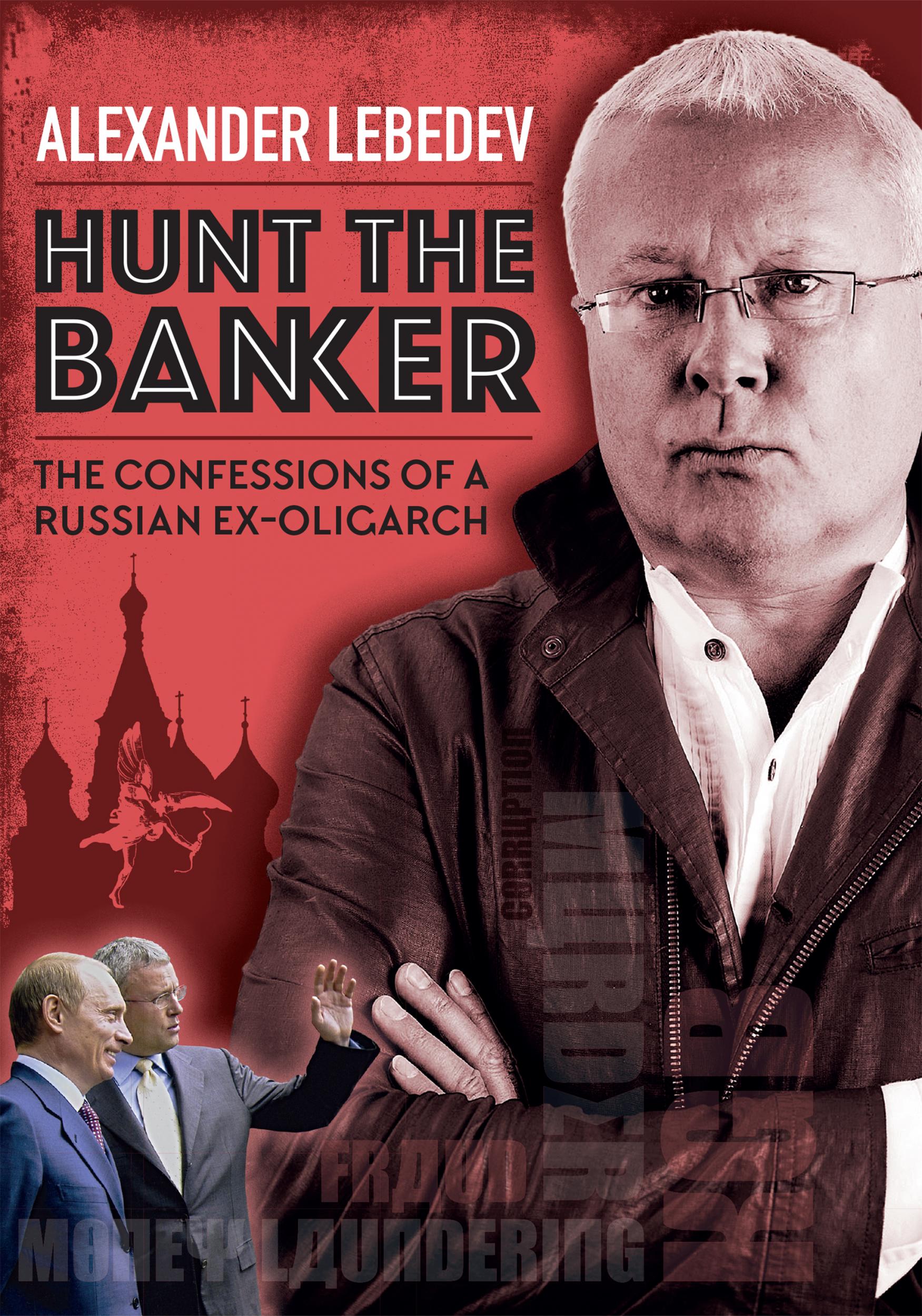

Alexander Lebedev is the father of Evgeny Lebedev, a shareholder in The Independent. His new memoir, Hunt the Banker, is published by Quiller on 12 September, priced £20. Order from bookshops or www.quillerpublishing.com