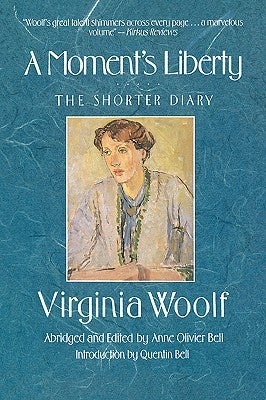

Book of a lifetime: A Moment’s Liberty by Virginia Woolf

From The Independent archive: Gyles Brandreth on the heartfelt diaries of a modernist great

For half a century I have been hooked on diaries – my own and other people’s. I began to keep a journal in 1959. I wrote my first entry on my first night at boarding school, by torchlight, underneath the blankets. My inspiration was the diary of Samuel Pepys. I had been given a copy, “suitably edited”, for my 11th birthday.

Over the years I have collected published diaries by the dozen – from James Woodforde’s Diary of a Country Parson (a window on the 18th century and a constant delight) to the 1970s Senate diary of George Aiken (very heavy going). For many years, my favourites were the wonderfully waspish diaries of the MP and social gadfly, Sir Henry “Chips” Channon, and the good-humoured, good-hearted post-war diaries of Noel Coward.

Then, 10 years ago, for Christmas, the actress Eileen Atkins gave me a copy of A Moment’s Liberty: The Shorter Diary of Virginia Woolf. Eileen said, “The joy of the diary is that there’s a gem on every page” and proved her point by opening the book at random and putting her finger on 18 May 1930: “The thing is now to live with energy and mastery, desperately. To despatch each day high-handedly. So not to dawdle and dwindle, contemplating this and that... That is the right way to deal with life now that I am 48 and to make it more and more important and vivid as one grows old.”

Woolf began her diary on 1 January 1915, when she was 32, and maintained it, with few interruptions, until four days before her suicide in March 1941, aged 59. It is the work of a great writer (of course), but unlike some of her novels (for me at least), it is wholly accessible: human, humane, witty and wise.

The diary takes you right to the heart (and soul) of the woman – as wife, sister, daughter, neighbour, friend, employer, writer – and provides a searing, sometimes merciless, often hilarious portrait of her circle – that infuriating Bloomsbury set – and her age. To the last, she follows Henry James’s maxim: “Observe perpetually.” She never stops. Her eye is uncanny and her turn of phrase flawless.

Through a quarter-century, we follow her ups and downs, admire her courage, feel her pain, share her prejudices. She is not so snobbish as I had expected and far funnier. Her love for her husband, Leonard, is very moving; her devotion to her craft both humbling and inspiring. With the diary, you are always there in the room with her (“It is very quiet here, not a sound but the hiss of the gas”); in every line, you hear her voice, crackling with high intelligence.

She provides gossip, intellectual rigour and the quotidian detail that is the hallmark of all the most memorable diaries. Three weeks before her death, she is struggling with the challenge of cooking haddock and sausage meat. The last line of the diary reads: “L is doing the rhododendrons...

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks