Van Gogh's Letters: The Artist Speaks, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

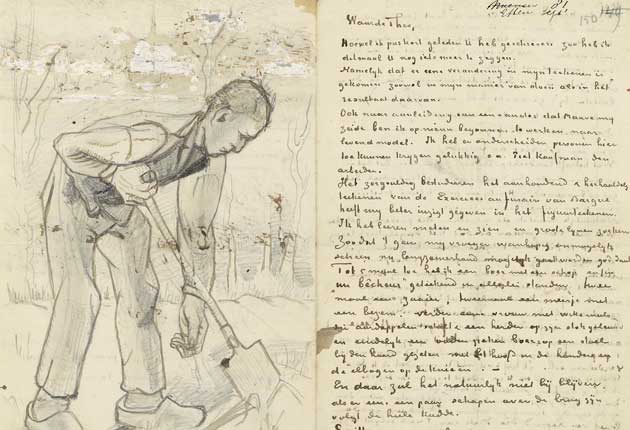

Your support makes all the difference.This is a show of words and images because Vincent van Gogh was adept in both forms. He left more than 800 letters, which have been newly translated and re-published in six fully illustrated volumes, and he made about 900 paintings during his short lifespan, of 37 years.

The aim of this exhibition, which engulfs almost the entire museum (only the basement remains a Van Gogh-free space), is to show us letters beside paintings and some of the other kinds of images he made – drawings and prints, for example. Of the 300 objects in the show, about 120 are letters. And they are not facsimiles, either. These are the marvellously fragile originals, often displayed on upright panels of glass so we can read both close-packed sides of the page.

A bigger version of the show will open at the Royal Academy in January 2010, but bigger will not necessarily mean better. Just different. There will be more paintings in London (this show is largely dependent upon the Dutch museum's own holdings), but fewer letters, because many are too fragile to travel. When Van Gogh wrote, he often punished the paper – he pressed on hard, he interrupted his words with drawings. These drawings were often heavily inked, and down the years this ink has settled and seeped through, sometimes obliterating the words on the verso.

Such is the nature of real, perishable things. We feel humble before them, as if we need to seize them once and for all, with our eyes, before they vanish back into the gloom of the vaults forever. These letters are often emotional war zones, especially when the script is at its tiniest. Van Gogh often wrote incredibly neatly – it is as if his hand is being guided by a ruler – but when he gets drunk on the local stuff, or when he is in a towering rage, which happens quite often, he reels and rocks all over the place. Then his lines can look like ships in distress at sea.

What we have here then is a fascinating, extended exercise in spasmodic autobiography. We read what Van Gogh aspired to do, and then we look at what he succeeded in doing. He tracks himself from first to last, commenting upon his life and art, describing what he is seeing. He was addicted to the depiction of reality – that's how he put it. But his reality was not another's person's reality, of course.

To 3 January 2010 (+31 (020-570 52 43; www.vangoghmuseum.nl)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments