Bookshelf avalanche? Confessions of a bibliomaniac

Books, and their acquisition, have obsessed readers across the ages. Can this paper-borne addiction last into the digital age?

At the beginning of his famous novel The Naked Lunch (1959), William Burroughs includes what he calls a "deposition: a testimony concerning a sickness" (my copy of the book, a nice tight hardback, with original dust jacket, published by John Calder, was bought secondhand from an old junkshop in Chelmsford that I used to visit with schoolfriends at weekends in search of cheap paperback Beats, and Jean-Paul Sartre, and Albert Camus, and the Picador Richard Brautigan, and Borges, and Philip K Dick).

Burroughs is writing about his fifteen-year addiction to "junk" – opium and all of its derivatives, including morphine, heroin, eukadol, pantopon, Demerol, palfium and a whole load of other stuff that he had variously smoked, eaten, sniffed, injected and inserted. "Junk," Burroughs writes, "is the ideal product… the ultimate merchandise. No sales talk necessary. The client will crawl through a sewer and beg to buy… The junk merchant does not sell his product to the consumer, he sells the consumer to his product… The addict… needs more and more junk to maintain a human form. . . [to] buy off the Monkey."

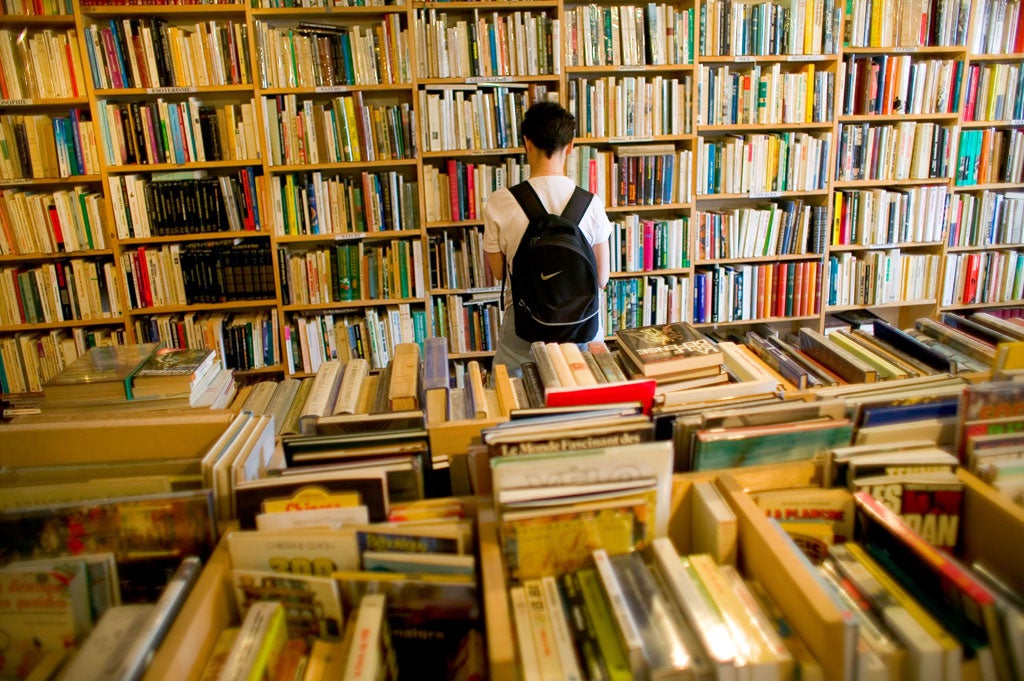

The chances are, if you are reading my book, you are no better or worse than William S Burroughs. The chances are, you have a serious problem: you're an addict. You have been sold to a product. You have a monkey on your back. And that monkey is made of paper.

(But it's OK. You are not alone. Here's where I'm at: I am wearing a pair of dirty, brown, broken slip-on boots that my sister bought for me about ten years ago; in both boots the sole is split right across the middle, and I have attempted to fix them with super-glue. I have two other pairs of shoes, but they too are broken, too broken in fact for me to be able to patch up, and they have therefore required professional attention and are currently awaiting collection from the excellent boot and shoe repair shop – motto, "Shoes Good Enough To Wear Are Good Enough To Mend" – just off Botanic Avenue in Belfast.

I am wearing a shirt that the father of a friend of mine kindly sent me a few years ago, when he'd retired and was throwing out all his old work clothes and buying leisurewear. All of the shirts are made of a drip-dry nylon – Alagon – of a kind now unavailable for reasons not at all clear to me; you get used to the rashes after a while, and the benefit of not having to iron the shirts surely outweighs any slight skin complaint the material may cause. My trousers are one of the two wearable pairs that I'm currently running, and they're in pretty good condition, although they are covered in green paint from a couple of summers ago when I was painting the shed where I work in the garden. My jacket is circa 1990.

And I am standing in the War on Want bookshop, down at the other end of Botanic Avenue, in Belfast, ostensibly on my way home from work, and I have half a dozen books in my arms, and I know that if I blow all of my £20 spending money on these books I won't be able to get my shoes back from the cobbler, and I'll have to leave them there another week. They've already been in for a month, and the proprietor of the shop has started leaving messages for me on my answerphone. I have a decision to make. I buy the books. For the foreseeable future I shall continue to be dressing like a vaudeville comedian, or a character in a play by Samuel Beckett.)

The first documented use of the word bibliomania, according to my OED – the twenty-volume second edition, bought as a present to myself when I received the advance on my first novel, and which cost me the advance on my first novel, which meant effectively that I wrote a book to buy a book – was in 1734, in the Diary of Thomas Hearne, bibliognost, antiquarian and assistant keeper of books at the Bodleian. "I should have been tempted," writes Hearne, "to have laid out a pretty deal of money without thinking my self at all touched with Bibliomania."

Then in 1750 Lord Chesterfield writes, warning his son, "Beware of the Bibliomanie." But the word doesn't appear to come into popular usage until 1809, when the Reverend Thomas Frognall Dibdin publishes his book Bibliomania, or Book-madness; containing some account of the history, symptoms, and cure of this fatal disease. The disease, in Dibdin's mad, medico-rhapsodico account, manifests itself in a desire for first editions, uncut copies, illustrated copies, and a "general desire for Black Letter". Book madness, in Dibdin's diagnosis, is a paper-borne disease.

Yes, of course there were books before paper. As every schoolboy knows, for the first few thousand years or so of its existence, a "book" might have been a clay tablet or a roll of papyrus, and it wasn't until the coming together of three key components – ink, type and paper – in the giant technological leap forward that was the invention of the movable type printing press by Johannes Gutenberg in about 1450, that the book as we know it took off and took over. Nicole Howard describes the role of paper in the Gutenberg printing process in The Book: The Life Story of a Technology (2005): "When ready for a new job, the printer would order the requisite amount of paper from a warehouse. It would arrive in stacks, or tokens, of 250 sheets.

The night before printing began, the approximate number of sheets needed for the job were wet down and then stacked upon each other. The weight of the stack squeezed out much of the water, resulting in slightly damp sheets the next day. The moistness allowed the fibers of the paper to receive the ink in a way they would not, were they completely dry.

Taken individually from the stacks, the sheets were placed in the tympan. The frisket was then swung into place to cover the paper's margins, and then the whole unit slid beneath the platen. With a pressman's turn of the screw, the type – which had been inked with special leather pads – transferred the image to the paper. With the impression complete, the paper was removed from the press and hung to dry in the rafters of the shop."

And – hey presto! – welcome to the modern world. Books produced by this sort of method have been accorded responsibility by historians for everything from the scientific revolution to the Protestant Reformation to the collapse of the ancien régime in France, to the rise of capitalism and the fall of communism, and just about anything and everything in between. Books, as we know, transmit ideas, foment and ferment strong feelings, prop up and bring down governments, offer escape and enlightenment, and encourage variously greed, hate, love, self-love and self-help: basically, books make history, and are made by history.

And books, lest we forget, are made from paper. In fact, from Gutenberg on, we have come to identify books so closely with paper that it's nigh on impossible for us to divorce our idea of the book from its long-standing relationship with paper: they're a couple; it's the perfect marriage. Even now, after a brief, fun flirtation with the dynamics of hypertextuality back in the late 1980s and 1990s, e-books and their associated reading devices have come increasingly to resemble paper books in almost every regard: in their shape, size, feel and functionality.

Prophets and opponents of the new technologies continually insist that e-books are amazingly, shockingly, mind-alteringly, paradigmatically different from p-books, when in fact the truth is that they are drearily similar. All we need is an e-book reader that actually smells like paper – the I Can't Believe It's Not Paper Reader™ – and the impersonation of old books by new books will be complete. Paper books, a mere mechanism for conveying information, have become so closely identified with the information they convey that we have difficulty in believing that anything else really is a book. A young novelist recently told me that she was dissatisfied with the e-book deal her agent had secured for her because "It isn't the same as a real book deal" (not the same, that is, except for the pitiful advance, the risible royalties, the virtually non-existent marketing and distribution, and the handsome 15 per cent paid to the agent; no wonder so many aspiring authors are flocking to Kindle direct publishing).

Since paper books seem so clearly to embody knowledge it's hardly surprising that we have come to believe that the possessing of books is in itself sufficient to possess knowledge. In one of his great little intellectual jeux d'esprit Flann O'Brien imagines the range of services that might be provided by a professional book handler: "De Luxe Handling – Each volume to be mauled savagely, the spines of the smaller volumes to be damaged in a manner that will give the impression that they have been carried around in pockets, a passage in every volume to be underlined in red pencil with an exclamation point or interrogation mark inserted in the margin opposite, an old Gate Theatre programme to be inserted in each volume as a forgotten bookmark".

This is funny because it's true. Nowhere is the disease of vanity more evident than in books and our possession of books. Nowhere is the paper disease more virulent. Nowhere has paper asserted its power and prestige more clearly and aggressively than in books. Like ancient people we have come to believe in the magic power of a talismanic object: books our little household gods. The literary historian James Carey, going against the critical grain, has suggested that "the book was the culminating event in medieval culture", and "an agent of the continuity of medieval culture rather than its rupture". If so, we are living in the Middle Ages still.

This is an extract from 'Paper: an elegy' by Ian Sansom, published by Fourth Estate (£14.99) Copyright: Ian Sansom

This article will appear in the 20 October print edition of The Independent's Radar magazine

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments