The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Children at food banks: The reality of Britain's food poverty crisis

In every food bank I visited, children waited quietly as their parents collected food parcels. It is difficult to imagine what they were thinking, but it is clear their parents were in desperate need

Witnessing children in the UK visiting a food bank is truly shocking, but research tells us it is not uncommon. In the last six months The Trussell Trust has given out over half a million food parcels, more than 200,000 of which were given to children, many of school age.

But there are also many more food banks, often run informally by religious organisations and community groups. I identified three times more independent food banks than Trussell Trust services in my ongoing research in the North West of England, revealing the true scale of the crisis.

I have witnessed food banks become the last line of support for many families, and it is likely that much of the food insecurity in the UK is hidden.

An estimated four million children live below the official poverty line in the UK even though a majority live in households where at least one adult is in employment. It has been widely reported how some teachers have been providing food and dinner money for those children who have no food.

The issue of food insecurity among children is being highlighted this Christmas by The Independent and Evening Standard‘s Help a Hungry Child campaign to respond to the disproportionate impact food poverty has on children.

In every food bank we visited, we observed children accompanying their parents to collect food parcels. The children would just wait quietly. It is difficult to imagine what they were thinking, but it is clear their parents were in desperate need.

Often the food bank volunteers would find something to give to the children and the food parcel would be made up specifically to include food for them, such as breakfast cereal. At Christmas time there are usually some donated toys and chocolates to give out. While a comfort, this essential help is of course only a short-term fix.

A lack of food can impact on a child’s ability to concentrate in school but can also impact on their long-term health in adult life. This begins with nutrition during pregnancy. Around seven per cent of babies born in the UK are low weight (under 2.5kg) and this is thought, in part, to be linked to economic deprivation.

Visiting a food bank is not a particularly joyful experience, especially at Christmas. Our research identified how many parents had put off going because of embarrassment and shame.

One mother, aged 34, said: “It throws your pride out of the window...I am doing it for my kids, I am not going to make my kids suffer just because of my pride.”

A father-of-two commented on how uncomfortable he felt: “I was nervous coming here, I thought I had done something wrong...having to ask for food your ego takes a battering.”

Many parents we spoke to did not want to be seen having to rely on a food bank. One mother said she feared if anyone saw her they might report her to social services and she might lose her children if she was seen as not being able to afford to feed them.

Many families were facing difficult choices. People on low incomes can face higher costs for everyday essential goods and services and many parents had turned to the food bank as a last resort.

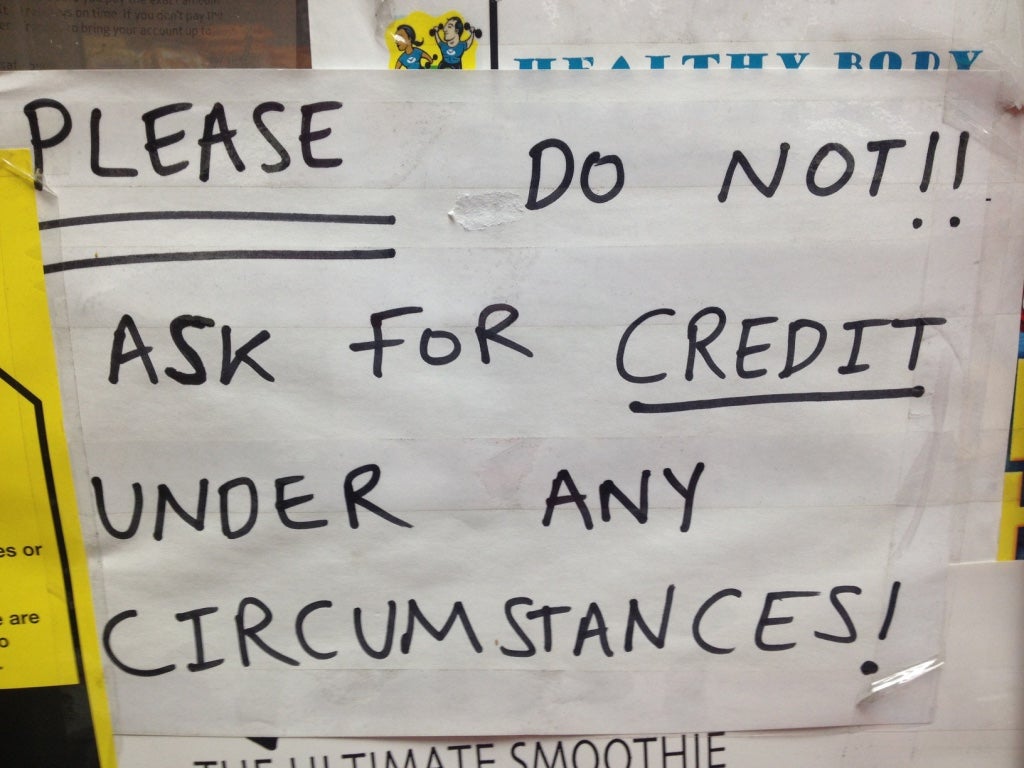

In one corner shop close to the food bank, there was a prominent hand written sign on the door, which read “Please Do Not!! Ask For Credit Under Any Circumstances!”

Another mother commented: “We need to keep the house warm and have just had to buy some new school uniform and that meant cutting down on something else.”

Evidence also suggests that many parents are skipping meals to make sure their children have enough to eat, which can put their own health at risk. One ten-year old child we spoke to highlighted how she was worried about her mother not eating. She said: “We say to my mum make sure you eat but she says she’s not hungry...she’s just making sure we eat first.”

Financial insecurity can affect children’s well being. Research by Step Change found more than half of children aged between 10 and 17 and living in households with problem debts reported feeling worried about their family’s financial situation.

Visiting a food bank is not free, it comes at a cost, it can impact on your self-esteem and pride. At Christmas, many food banks provide extra food parcels to cover the holidays. But food banks can only provide a temporary fix and are no place for children. Given the predicted increase in child poverty, it is likely that we will see more UK children in food banks in the future.

Unlike Oliver Twist the children we have encountered in food banks were not asking for “more”, they just seemed happy to have something.

Kingsley Purdam is a social statistics researcher at the University of Manchester

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks