Steve Richards: Labour deserves oblivion if it listens to the unions on pay

I begin with a little quiz. Who said the following words, and when? I will give you a clue, the second part of the question is at least as important as the first. Here are the words: "I have to level with you all ... a plan for growth now will help get the economy moving again and stop the vicious circle on the deficit – but by itself it won't secure our economic future or magic the deficit away. A steadier, more balanced, medium-term plan to get the deficit down will still mean difficult decisions and tough choices in the years ahead. Tough choices on tax and spending ... Discipline in public and private sector pay. And no matter how much we dislike particular Tory spending cuts or tax rises, we cannot make promises now to reverse them."

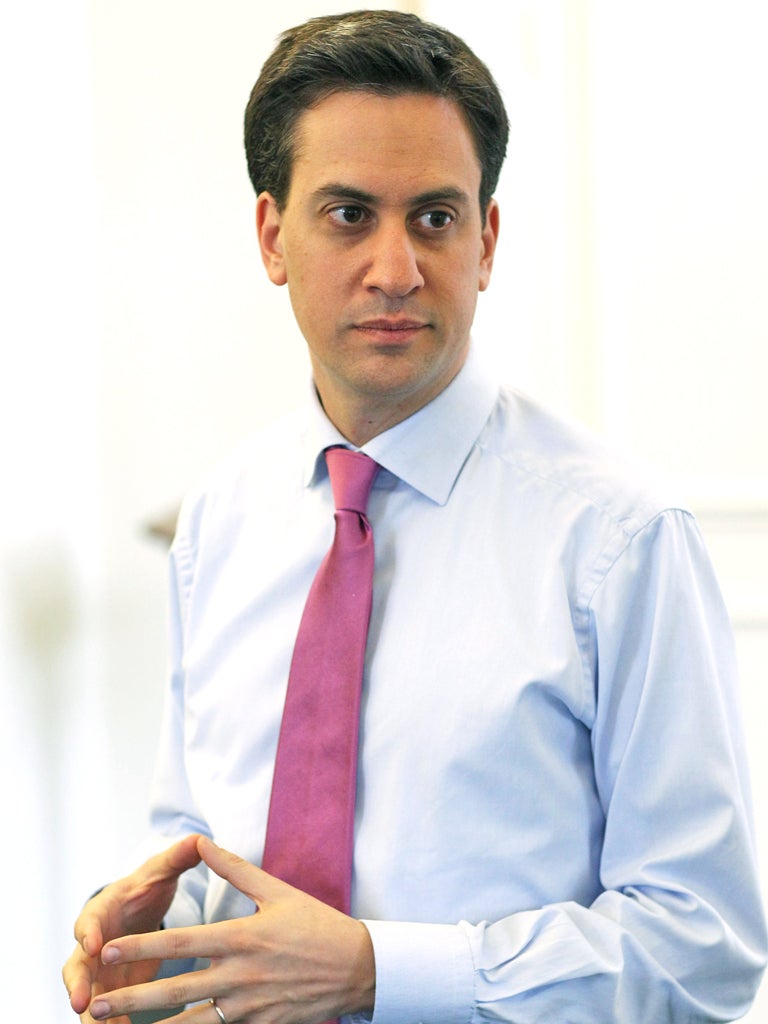

The words are from the Shadow Chancellor, Ed Balls. They are an extract from the speech he delivered at the Labour Party conference last September. The message is precisely the same as his argument outlined at the weekend. Yet the latest speech has triggered a row of near-seismic proportions with some unions, and a hint of respect from parts of the all-knowing chorus on Twitter which detects a profound switch from profligacy to prudence.

There was no switch. There was no U-turn. The approach is exactly the same as it was before. So what has happened? There is a single new element. On Saturday, Mr Balls gave a precise policy example, even though it was implicit last September, stating that he would apply the same limits to public-sector pay as the Government. Given that he was arguing for "discipline" on pay last year, this is not remotely surprising, but shows that a "policy" is more vivid than an argument that few can be bothered to follow because it challenges their view of what is being said.

But the frenzy also points to the deep insecurity within the Labour leadership. Let us pause a moment to recognise the perversity of their conundrum. Mr Balls warned in the summer of 2010 that the speed and scale of George Osborne's spending cuts would stifle growth. Last November, Mr Osborne admitted that he would not wipe out the deficit by the end of the parliament as he had planned, and that growth was non-existent. At the point when Mr Balls is vindicated, the unrelenting chorus of commentators demands an apology from him and continues to pay homage to the Chancellor.

Partly as a result of media pressure and also because of the opinion polls suggesting Labour is way behind on the economy, the party's leadership has panicked. By the leadership, I mean not only the two Eds, but those in the Shadow Cabinet briefing that it was necessary for the party to have an economic policy that was more "credible", or closer to the Tories' position, even though Mr Balls had made clear last September that he could not promise to reverse the cuts and would be tough on pay.

As a result, Miliband and Balls wanted the speeches of recent days to appear as a highly significant moment and yet one entirely in line with what they were saying before. When a party is in trouble, this is what happens. It shouts louder to be heard and then makes clear it has been shouting in the same vein for a long time, although I have heard none of them cite what was said last September as evidence, probably because they half-wanted recent statements to appear more significant than they were.

The key in opposition is to give the impression of a consistent unfolding narrative, which is why opposition is partly an art form. David Cameron was pretty good. Tony Blair and Gordon Brown were supreme artists in opposition. But when polls are poor, the media is on the rampage and there is a degree of internal dissent, attempts at artistry tend to be replaced by contradictory assertions of what is supposedly big and what is not.

Yet Labour's message before the weekend and after is not that complicated. As far as I can tell, it is this: "Under our policies in government, the economy was starting to grow again. The final borrowing figure for the last government was lower than forecasts expected. We warned that Osborne was making a terrible mistake by cutting further so quickly. Sure enough, growth is now virtually non-existent. Our warning was ignored. By the time of the next election, as a consequence of Osborne's policies and not ours, we will face even tougher decisions as the cake will be much smaller." Agree or disagree, it does not take a genius to follow the sequence.

Evidently, the union leaders cannot do so. Their response to Mr Balls's speech was even more over the top than from those who gave the non-U-turn the thumbs up, on the grounds that it was a U-turn. Not only were they fuming over a policy that, in effect, Mr Balls had stated five months earlier, but their parochial cries of pain ignored the fact that for several years, employees in the private sector have calculated that it was better to take real-term pay cuts than to have no job at all.

The debate about fairness in British politics is now becoming so vague and subjective, there is a danger it replaces the term "modernise" or "progressive" as an all-encompassing theme that comes to mean nothing at all. But for any aspiring governing party to argue now that its priority is to pay public-sector workers more after the next election in 2015 is a route to deserved oblivion. Instead, while fairness is the new political fashion, Labour should be probing much more precisely what it means to be "fair" in the era of the global financial crash, not only in relation to bankers and other top earners.

Is it fair that wealthy parents receive child benefit, or affluent pensioners travel free in London while poor earners have to pay up to £10 a day? Is it fair that health workers in expensive parts of the country are much worse off than those in areas where accommodation is cheap?

Under Gordon Brown, the two Eds ventured tentatively on to this terrain, suggesting that child benefit for older children should be invested in education or training, and raising the possibility of regional pay deals in Mr Brown's 2003 budget. Nothing happened, partly out of fear of the unions.

Some of the union leaders are threatening to break formal ties with Labour. The party's leadership should be relaxed about such a prospect, but I doubt that it is.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks