More than a baseball park – a true American icon

The history of Boston Red Sox's famous 100-year-old home stretches far beyond bats and Babe Ruth, says Brian Viner

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.These might be the maunderings of an embittered Everton supporter who was at last Saturday's FA Cup semi-final, but really, haven't things come to a pretty pass in English football when Liverpool play Everton at Wembley and the former's two principal owners aren't even there, citing a conflicting commitment to their first sporting love, the Boston Red Sox baseball team?

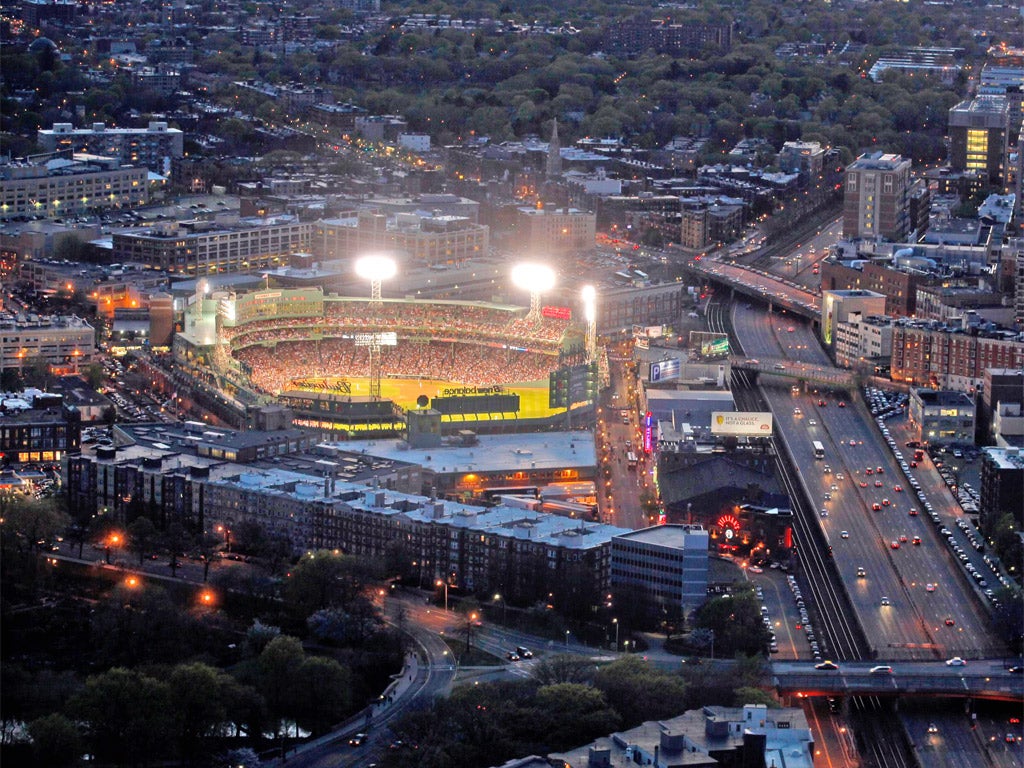

Still, in fairness to John W Henry and Tom Werner this is quite a season to be a Red Sox fan, let alone a Red Sox owner, for it marks the centenary of the team's venerable and atmospheric home, Fenway Park.

Tomorrow, it will be 100 years to the day since the purpose-built ballpark hosted its first major league game. An icon of Americana had been born, later becoming one of the 150 buildings chosen by the American Institute of Architects as having defined "The Shape of America". Today, it is revered for its history and, in an era of edge-of-town super-stadia, its central Boston location, its smallness and quaint idiosyncrasies.

In April 1912, however, it represented modernity. Most American ballparks were still made of wood, and since many of them also were located close to railroads, fires started by sparks from passing trains were regular occurrences. The new Red Sox home, by contrast, was built in brick and steel, the same components that seemed to have forged one of its earliest heroes, a moon-faced phenomenon called George Herman Ruth.

Boston fans loved Ruth, the man they called "Babe" and "Bambino", and mourned on 26 December 1919, when he was sold to the New York Yankees. The mourning continued until 2004, when the Red Sox won their first World Series since 1918, a drought ascribed throughout baseball to "the Curse of the Bambino".

Despite that 86-year failure, Fenway Park hosted many of baseball's epic moments greatest heroes, few greater than the slugging colossus Ted Williams, whose .406 batting average in the 1941 season has never been surpassed or even matched.

If Fenway Park had known only baseball, it would still be one of America's most cherished cultural shrines, but it has witnessed much besides. In 1944, President Franklin D Roosevelt delivered his final campaign speech there. Three days later, he won an unprecedented fourth term. As for the likely protagonists in this year's presidential election, both have turned Fenway's unique aura to their advantage: Mitt Romney used it to host a barbecue for campaign donors, and Barack Obama held a fundraiser there during his first run for the White House.

Nevertheless, it is baseball with which Fenway is synonymous, even though it is in many ways unsuited to the modern game. It is squeezed into an urban space that by any sensible measure is too small for it. It is a place of quirks, none quirkier than the so-called Green Monster, the wall 240ft long and 37ft high that runs along the side of the abnormally short left-field. It is to Fenway what the Kop is to Anfield: part of the very soul of the place.

That soul has been threatened down the years. In 1965, the Red Sox owner Tom Yawkey declared his intention to tear down the "hopelessly outdated" ballpark and build a handsome new arena. Similar plans were mooted 35 years later, when the Red Sox general manager, Dan Duquette,said: "The longer we wait, the further behind we'll fall."

The parallels with the Premier League are striking and in England Anfield is one of the grounds deemed to be commercially inadequate.

Significantly, though, it was Henry and Werner, after their consortium bought the Red Sox in 2001, who rejected the scheme to demolish the old stadium and build a swankier look-alike, preferring a programme of sensitive refurbishment and renewal. "You don't create an imitation if you have the real thing," said Werner.

It is unlikely he and Henry feel as sentimental about Anfield. Still, at least they will be attending the FA Cup final on 5 May – even though it clashes with the visit of the Baltimore Orioles, the Red Sox's nemesis last season, to their beloved Fenway Park.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments