Delay awarding Olympic medals for eight years, says biochemist

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Medals won at the London Olympics should not handed out until 2020 because it will be years before testers can be sure that the athletes did not take drugs, a leading sports scientist has suggested.

Samples taken from athletes at the London Games will be held for eight years at a new anti-doping laboratory in Harlow, Essex, allowing biochemists time to catch up with substances that are currently undetectable.

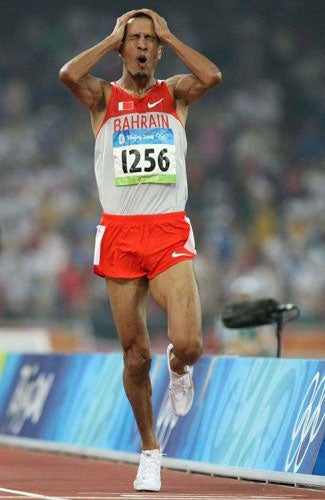

This policy of retrospective testing has operated with success before, most notably when the 2008 Olympic 1500m gold medallist Rashid Ramzi of Bahrain was stripped of his title in November 2009, a year after crossing the finish line in Beijing.

Professor Chris Cooper, a biochemist at the University of Essex, also warned of a potential "perfect storm" of drugs development as cheating athletes exploit medical breakthroughs by pharmaceutical companies.

He said that blood doping, a form of cheating said to be popular with some Tour de France cyclists which involves artificially increasing the amount of red blood cells in the body, had attracted the interest of big pharmaceutical firms because it has implications for the treatment of leukaemia and cancer.

Erythropoietin (EPO) is the hormone that causes the body to produce more red blood cells, of particular interest to endurance athletes. The body produces it naturally under situations of "hypoxy" – when it is not getting enough oxygen, hence the effectiveness of high-altitude training. Scientists have only recently developed tests to check for injections of artificial EPO, which is particularly difficult to monitor as the substance also occurs naturally in the body.

"The big pharmaceuticals, they are interested in this pathway, in producing EPO. They may develop new compounds, new molecules, new methods of boosting red blood cell count," Professor Cooper, author of Run Swim, Throw, Cheat, said. "Sports don't have the money to develop these drugs themselves, they might cost £1bn, but the pharmaceutical companies do. These companies do talk to the anti-doping people, and rightly so, but new compounds could still find their way back into sport, long before any effective test for them could be developed. It's unlikely athletes will be taking drugs at the actual Olympics, anyone cheating will have done so long beforehand. But we might not find out for many years."

Lord Coe has consistently issued strict warnings, saying: "You come to London and you try to cheat, we will get you."

At the Harlow laboratory, samples will be subject to what the centre's director Professor David Cowan, from King's College London, has called "total data capture". The samples will not simply be tested against the 200 banned substances, but will also be examined for anything not previously encountered.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments