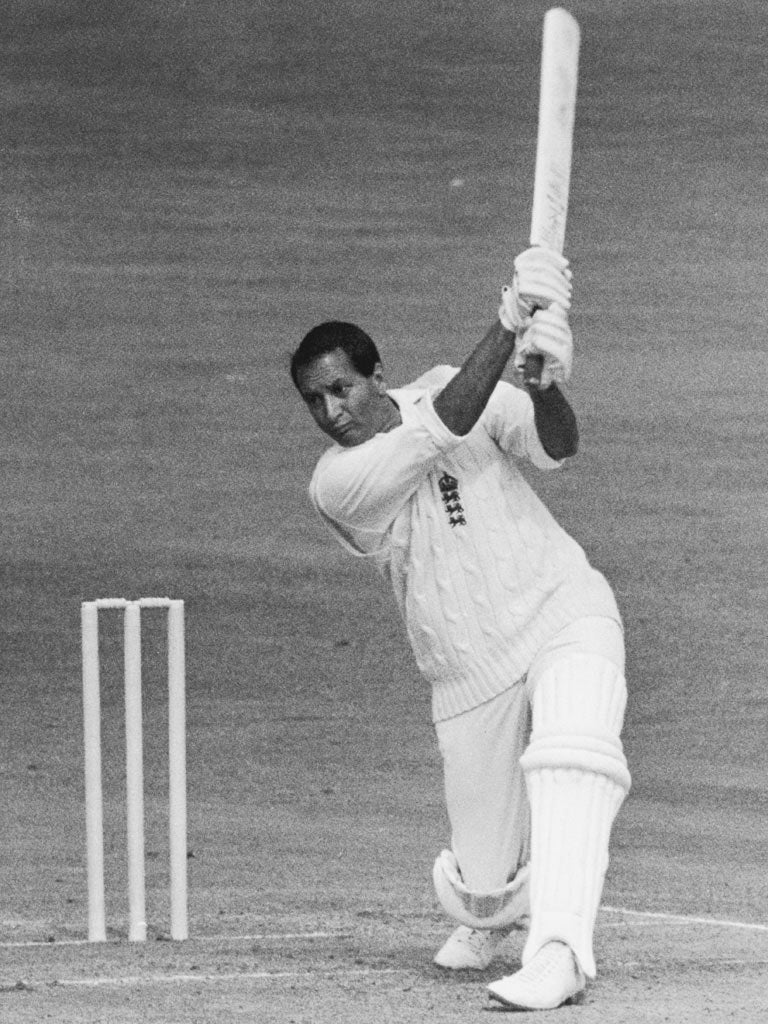

Dolly's 158 forced sport to put conscience first

All-rounder's return to form in 1968 made it hard to exclude him from the aborted tour to South Africa, writes Stephen Brenkley

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Basil D'Oliveira was an unlikely revolutionary. All he wanted to do was play cricket to the very best of his ability. But when he arrived in Lancashire in the cold, cheerless spring of 1960 from his home in the poor, downtrodden suburbs of Cape Town he set in motion a staggering chain of events.

In the controversy that still surrounds what became known as the D'Oliveira Affair, it is too easy to overlook what an outstanding cricketer and naturally dignified man he was. But it was the game and only the game that brought him 51 years ago to Middleton, on the outskirts of Manchester, from Cape Town.

He became a force in the Central Lancashire League, he joined Worcestershire and a year later, having been granted a British passport, he made his Test debut. From the time he became established in England's Test team he set his sights on the South African tour of 1968-69. The South African Government was equally determined he should not come.

The summer of 1968 was important for England. The Ashes were being played for. D'Oliveira, "Dolly" by then to the English public who had taken this determined, capable cricketer to their hearts, was out of the side for much of the 1968 series. He had been on tour to the West Indies in the preceding winter and had a dreadful time of it. His form on the pitch was indifferent and off it he had enjoyed the delights of the Caribbean. The teetotaller who had arrived in England now liked a pint as much as the next man.

He kept his place for the first Test against Australia and scored a fighting, unbeaten 87 in a 159-run defeat. But it could not prevent his being dropped for the next match, in the interests of team balance, and his form thereafter nosedived.

Sensing his chances of going back to his homeland as a fully fledged international sportsman were receding, Dolly could barely make a run. There were still shenanigans behind the scenes as South Africa sought to ensure he would not tour. D'Oliveira was offered a coaching job in South Africa, on the condition he would make himself unavailable to tour. Other non-whites in his homeland accused of him of selling out.

Then came the fifth Test. D'Oliveira was not in the original party. Nor was he summoned when it was decided the pitch might be ripe for medium-pacers. Two cricketers, Tom Cartwright, whose part was to grow later, and Barry Knight, had to decline the opportunity to join the squad because of injury. So D'Oliveira was brought in.

Even then, as fourth reserve, it looked improbable he would play. But, on the eve of the match, the opening batsman Roger Prideaux withdrew, citing a virus. Years later, it would transpire that Prideaux was trying to protect his place in the touring party, which he feared failure against Australia might affect. So D'Oliveira played.

When he was on 31, he edged Ian Chappell's leg-spin to Barry Jarman, Australia's keeper, who spilt the chance. A score of 31 would have made it easy for the selectors to do what they did anyway. But D'Oliveira made the most of his reprieve.

England won the match to level the series and it was D'Oliveira who took the vital wicket on the last afternoon which provoked Australia's ultimate collapse. The selectors gathered for their fateful six-hour meeting and the upshot was that D'Oliveira was not included. The parts played by the selectors, chaired by the respected Doug Insole, and the captain, Colin Cowdrey, whose reputation has suffered with the passing years, remain mysterious.

D'Oliveira was distraught and the country's sporting followers were apoplectic. In hindsight, there were possibly reasonable cricketing arguments for omitting D'Oliveira, although a score of 158 under such personally difficult circumstances tended to rebuff all of them.

But the tour would probably have gone ahead and history might have panned out differently. In mid-September, three weeks after the party was announced, Cartwright, one of the seam bowlers, withdrew because of his chronic shoulder injury. For some reason, the selectors now installed D'Oliveira. It seemed odd then and in cricketing terms it seems odd now.

By the selectors' own account, D'Oliveira had been considered for the original party only as batsman, although he also bowled adequate medium pace, and Cartwright, though he could bat, had been selected as bowler. MCC had bowed to public and press pressure. South Africa cancelled the tour and England would not play them at cricket again until 1993.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments